A few years ago, college student Alice* was browsing through products online when Amazon’s “inspired by your browsing history” recommendation system suggested a book called Spinster: Making a Life of One's Own.

“As if I didn’t already feel bad enough about my dating prospects, the algorithm had to rub it in,” Alice joked. “Not that it’s bad to be single, but I do think the word ‘spinster’ has a sort of negative connotation.”

Alice wasn’t sure what had given Amazon the idea that she was interested in spinsterhood, but it was true that she had never had much luck with dating. To prove one algorithm wrong, she found herself turning to another. “My friends had been telling me to try dating apps for a while. I finally caved.”

Alice is far from alone. A 2019 survey by the Pew Research Center found that 30% of US adults have used a dating app or site, and that percentage nears 50% for people ages 18–29.

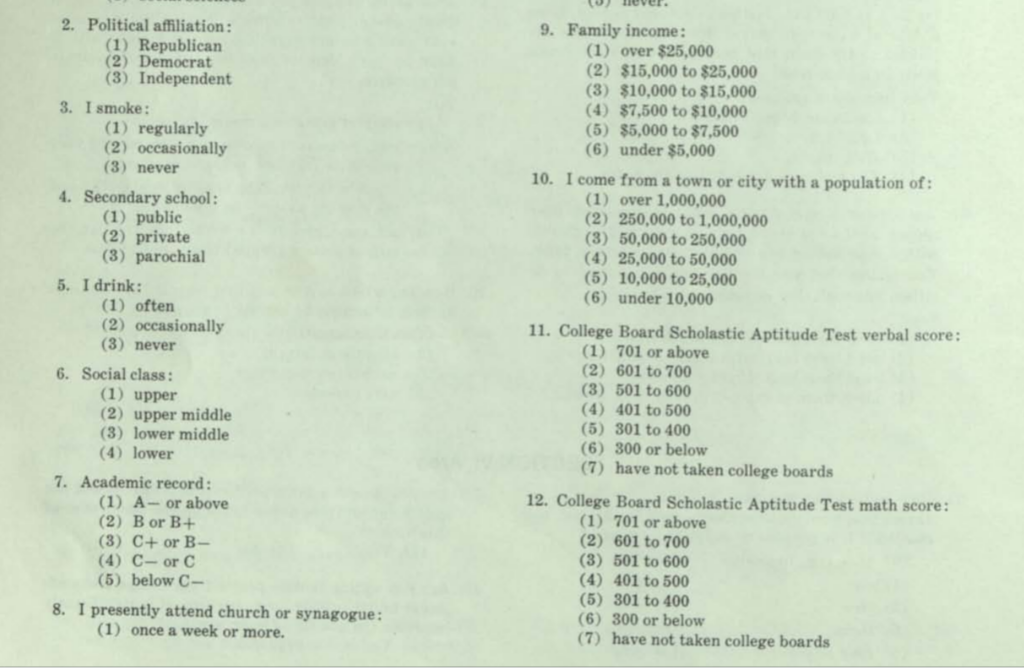

“Swiping right” may be a modern phenomenon, but did you know that the first US computer dating service, Operation Match, started in 1965? An IBM 7090 computer matched participants based on their responses to a detailed questionnaire (excerpt above), which included questions about social class, “sexual attitudes,” family income, intelligence, attractiveness and body weight. See the full questionnaire.

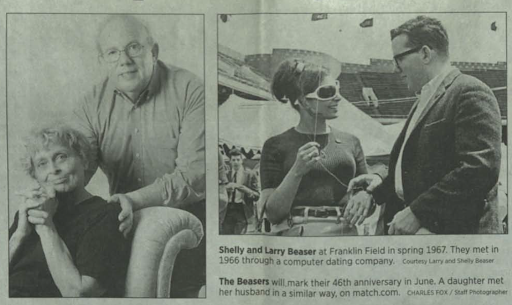

Two generations of computer dating services: Shelly and Larry Beaser met through Operation Match in 1966. Their daughter (not pictured) met her significant other through Match.com. Read the 2015 Philadelphia Inquirer article.

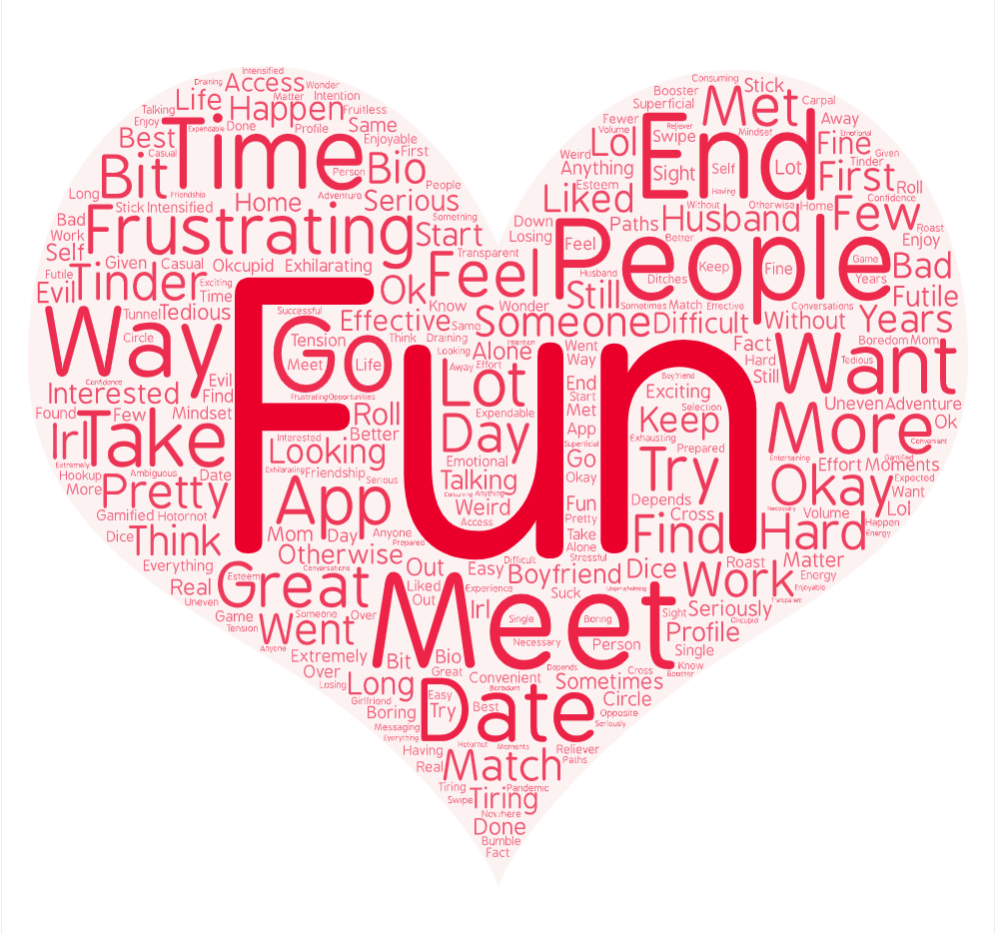

I created a survey to gather personal feedback about online dating from friends and friends-of-friends. Their thoughts and stories appear throughout this article. I asked survey participants to describe in a few words their experiences with dating apps overall and made the word cloud below to visualize their responses:

It’s clear that many people have found the experience fun—this is good! But terms critical of dating apps vary and, for that reason, don’t appear as prominently. Looking close, you can see words like “frustrating,” “tiring,” and even “futile.”

Particular concerns preoccupied many of the survey respondents, including: harassment and bullying; fake accounts or scams; other users misrepresenting themselves to appear more desirable; and, unwanted messages and attention.

Since these issues stem from bad behavior on the part of users, you might feel tempted to absolve the platforms of responsibility. Maybe it’s reasonable to assume that someone who behaves poorly online would behave just as poorly in a physical space, as one respondent suggests:

Though I agree that neither is inherently better or worse, there are significant differences between these two settings. I’ll discuss some of them below.

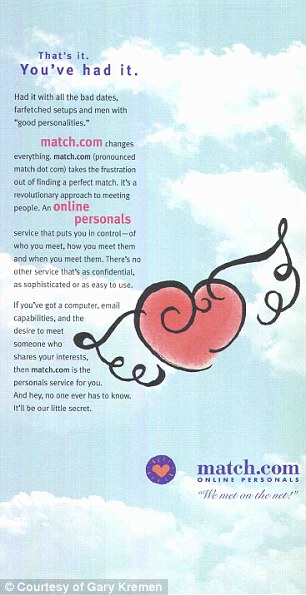

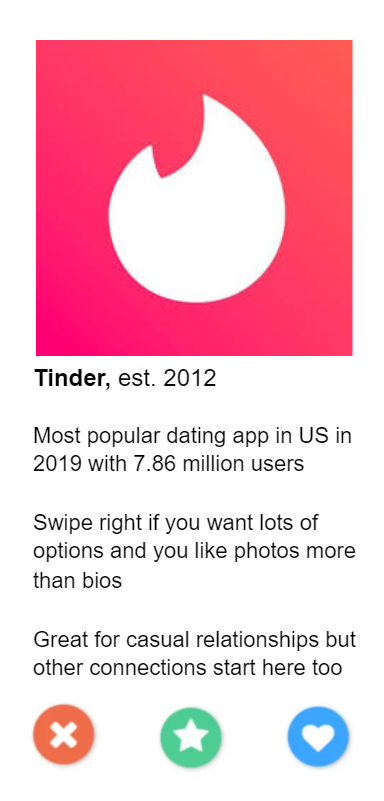

Match.com was one of the first and most popular dating sites when it launched in 1995. While the internet has come a long way since then, frustration and bad dates unfortunately seem to be timeless. Today, Match Group is a giant in the online dating space and owns Tinder, Match, OkCupid, and Plenty of Fish, among other services.

In a bar or any other public place, an algorithm does not filter who we see, or who sees us—rather, we “filter” people through our own preferences and biases. The pool of options is much smaller than on an app, but potentially anyone in the room can see and talk to us.

On an app, filtering begins from the moment we start swiping. We make decisions about who we like or don’t like, but we don’t know how the app will interpret our decisions or who it will recommend based on them. After all, what does it really mean for one user to be “similar” to another? Do they have similar hobbies, jobs, ages, or something else? The following comment indicates that hobbies play a significant role:

This seems fairly harmless and potentially useful. But consider this comment: “If I swipe on one Asian guy, suddenly my feed is full of Asian guys.”

Tinder, for one, says its algorithm does not store information about race or income and is “designed to be open.” But if the app is not filtering by race, how did the above situation occur? The participant below highlights a concerning trend:

The algorithms seem to have been designed with certain assumptions in mind: that the qualities we believe we want in a match are the qualities we actually want; that the people we swipe right on today indicate who we will like tomorrow; that apparent similarities between users reflect significant patterns that will determine whether we will like them. An effect of these assumptions may be a lack of diversity in our potential matches.

To recommend potential matches, Tinder’s algorithm relies on location and prioritizes users who are active at the time. It also takes users’ behavior on the app into account. If I swipe right on several profiles that other users similar to me have swiped right on, the algorithm will recommend more profiles that those other users have liked too.

Tinder points to data showing that the number of interracial marriages in the US has increased since the app was introduced. It’s true that the rate of interracial marriage has consistently increased over the past 50 years, with bumps after Match.com, OkCupid, and Tinder, respectively, became popular.

Of course, the data does not prove that Match, OkCupid, or Tinder caused those increases in interracial marriages. If Tinder has played a part, it may not be because of its algorithm’s “openness” so much as the app’s ability to introduce users to a greater variety of individuals far beyond their social circles.

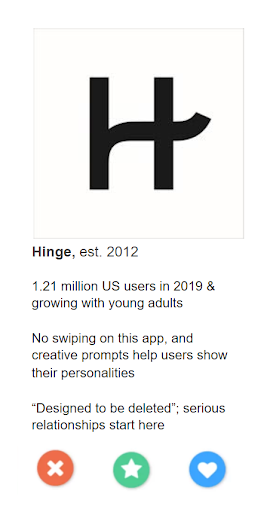

Consider apps like OkCupid and Hinge that do allow filtering by race. Both companies claim that some minority users find this filter useful for finding other users like themselves, perhaps helping prevent people of color from coming into contact with users who discriminate against them.

But could it also cause certain groups to be marginalized? OkCupid found that Black women and Asian men are least likely to receive messages or responses on the platform. According to a 2014 study, 80% of white dating app users on an undisclosed “major online dating site” exclusively messaged other White users, while only 3% of all messages from White users were sent to Black users.

The opportunity to learn and grow by meeting people who are different from us should be, I think, one of the best benefits of online dating. It is disheartening when the opposite occurs.

Unfortunately, some users act on their biases in ugly ways. Sometimes the app’s environment generally feels unsafe.

It can take the form of overt racism. As one respondent reported: “I’ve had people be straight up racist towards me (calling me a chink, saying they have yellow fever, etc).” And there can be other kinds of abusive language, such as, “I’ve experienced my fair share of harassment, and dating sites are no different. Being plus-sized, especially speaking with men, people believe that you should be thankful someone even breathed in your direction. And when you don’t jump at the chance... they retaliate with mean words.”

I do wonder if the nature of dating online makes this type of harassment a bit easier. There are no witnesses to these online discussions, and unlike physical places like bars, apps are not subject to laws against discrimination. The harasser can more easily dodge accountability. However, users can perhaps avoid the possibility of physical violence, though not necessarily the threat of violence.

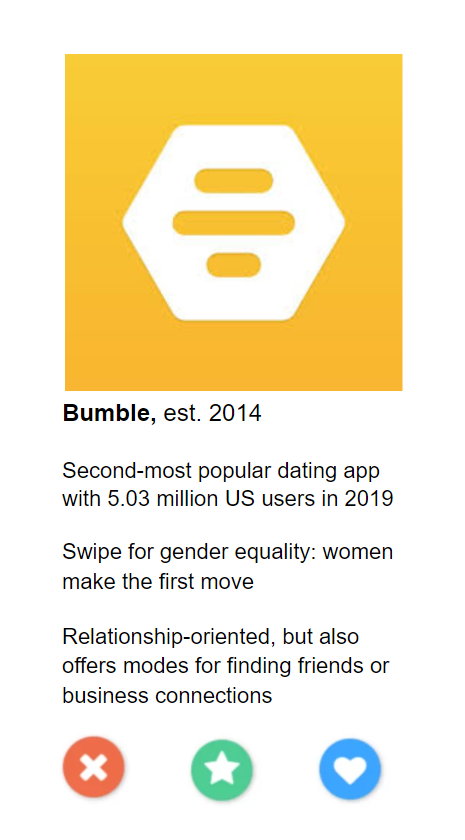

Bumble reveals very little about how its algorithm works, but some suspect it is similar to Tinder’s (despite its special focus on empowerment). We do know that the platform was built with gender equality in mind, as it only allows women to make the first move. A notable feature, “Private Detector,” uses AI to automatically blur nude images received in the app’s chat in case they are unsolicited (1 in 3 women have received a nude image they didn’t ask for, according to a national survey).

What are dating app companies doing to hold harassers accountable on their platforms? Bumble has explicitly banned “unsolicited and derogatory comments... that can be deemed fat-phobic, ableist, racist, colorist, homophobic or transphobic.” Several apps allow you to report users for bad behavior and Tinder, for example, will flag the reported profile for review by moderators. If everything works properly, you will never see the harasser in your feed again.

This won’t necessarily help, though, if you have already exchanged contact information and communicated outside of the app. Some guys I’ve chatted with have been quick to ask for my phone number, often before I feel comfortable sharing it.

The situation becomes even less clear when it comes to in-person meetings. Though the apps often facilitate these meetings, should they be held responsible for what happens during them? It probably isn’t the app’s fault if you don’t hit it off with your date, but what if something much more serious happens?

I received several comments from respondents who were concerned about the risks of connecting with people they didn’t know. Some of these worries stemmed from the possibility of other users misrepresenting themselves online.

The above, unfortunately, may be a best-case scenario for what can happen when users lie. Here are some less desirable outcomes: “One time, this guy said he was 22 but he turned out to be only 18. We were supposed to go to a bar but his fake [ID] got busted by the bouncer and he threw a fit." And, “When I first started using Bumble I got scammed by two guys that I was supposed to meet but they didn’t call or [FaceTime] or see me because I think they were fake.”

Several respondents expressed concerns about their date turning violent (more than one specifically mentioned a fear of meeting up with a murderer).

To protect themselves, several respondents reported taking measures like meeting in a public place, telling a friend the location of the date, and having a plan for what they would do in an unsafe situation. One respondent suggested that dating apps could help by providing safety guidelines to users. Another said, “There really are very few to no safety guidelines provided on dating apps, which is incredible when you think that this is effectively a service which helps you meet strangers off the Internet! Basic advice... would—if nothing else—be a useful prompt to first time users and even a reminder to those who've been on the platform a little longer.”

This solution would likely help, but I wonder if even more could be done. Might dating apps be able to predict abusive behavior by detecting key words in user profiles or chats, or suspicious matching/unmatching habits? Could something be done to prevent abusive users from joining in the first place, like adding additional verification steps? It would be great to see dating apps use their algorithmic power to fight harassment wherever possible.

There is no swiping on Hinge, and rather than simply liking a profile as a whole, the app forces you to like something specific about it, either a photo or a prompt response. Hinge also has a feature called “Most Compatible,” which uses cumulative data and machine learning to recommend compatible matches to the user. The feature works by finding patterns between the people that users have liked or rejected, then comparing them to other users’ patterns. If you think this sounds similar to Tinder’s algorithm, you may be onto something.

There is far less stigma attached to online dating today than in the internet’s early days, when its users made up a small percentage of the population. Most of my friends in the Gen Z/Millennial age groups use dating apps, and actually meeting someone you want to date (and who wants to date you) in a physical space seems remarkable.

Still, if you have shared your online dating experiences with someone who has not dated online, you may have heard something like, “I’m so sorry you have to go through that!” or “What if your date turns out to be an ax-murderer?” And there are those who don’t believe a relationship formed online can be as meaningful as one formed through conventional means.

For the record, “meet cutes” are not always so cute, as evidenced by this uncomfortable scenario:

Yet there is concern even amongst dating app users that dating apps are not facilitating meaningful connections. One said: “I do feel sometimes that it's become so gamified that we're losing sight of the fact there's a person at the other end of all this. It can make you feel a bit expendable at times—like someone better than you is just one swipe away—and I wonder if that affects how much effort people are prepared to put into their matches given it's so easy to log back on and keep looking rather than stick it out.”

One factor may be the sheer volume of options on dating apps. There is scientific evidence that our brains are not built to choose between hundreds or thousands of alternatives. We can get overwhelmed or, worse, plagued by a nagging sense that there might be someone just a bit better out there.

As it turns out though, swiping more doesn’t necessarily ensure better matches. The apps do “learn” from your behavior to an extent, but at a certain point, you will run through your “best” options and begin to see less compatible profiles. Essentially, the closer you get to the end of the dating pool, the less tailored your options become, and the guy you turned down 1,000 profiles ago starts looking pretty good compared to the bot trying to sell you Bitcoin. (If you do want that first guy back, you’re in luck! Tinder, Bumble and OkCupid have all recycled profiles that users rejected in the past.)

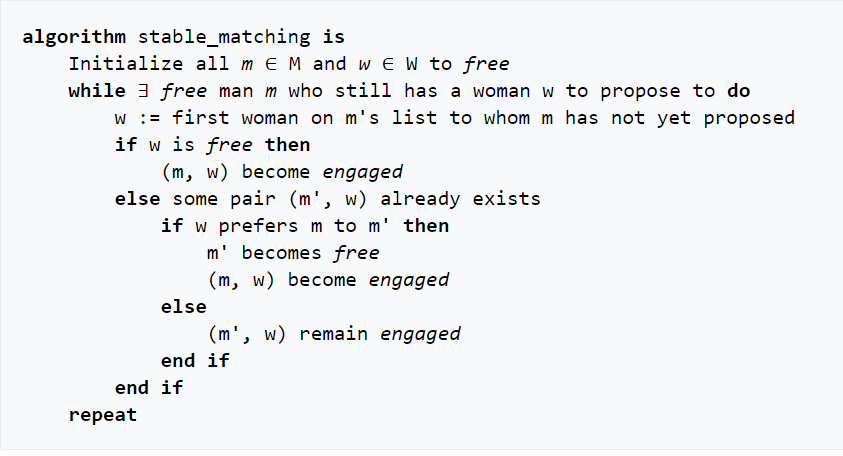

The Gale-Shapley algorithm was developed in 1962 as a solution to the “stable marriage problem.” The idea is that stable matches (meaning that there is no other possible pairing that both participants would prefer to the one they are in) can be made between equal numbers of two types of participants—in the above case, men and women. Today, Hinge supposedly uses an updated version of this algorithm that can make same-sex pairings and does not have the explicit end goal of marriage. That said, note that in the above example, because the men are “proposing” to the women, the matches will be better for all men than for the women. Making the first move can be empowering!

Is online messaging a less substantive form of communication than in-person interaction? Gaps between responses could make it more sporadic, and it might be easier to ignore a text message than something you hear face-to-face. It would also be easy to message several people at the same time, dividing your attention rather than focusing on one person. Consider this possibility, too:

It’s hard to predict how virtual and in-person conversations might differ, and whether any awkwardness results from nerves or true incompatibility. I personally feel more comfortable connecting with someone I don’t know well yet through writing rather than speech and, for this reason, online communication has been invaluable in helping me form and maintain meaningful relationships. Everyone is different, of course, and the reverse of my situation is true for many people. One said, “The constant need to keep on checking the app for matches is a little tiring. It is difficult for someone who prefers to talk rather than messaging.”

One way to mitigate several of the issues raised in this article—the fear that someone is not who they say they are, the potential danger of meeting in person, the difficulty of connecting through an app alone—may be a video chat. Safer than an in-person meeting but a closer approximation of one than messaging alone, a video conversation can help us safely gauge compatibility and determine if we want to meet in person. As for catfishers, they are unlikely to agree to a video chat, and if they do, they are unlikely to show up (if they do, their con is essentially over).

“But Emily,” you say, “I am so tired of video chats! All I do anymore is video chat!” This is certainly understandable in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. I still recommend it, though, as a safer, more affordable and less time-consuming way to meet a stranger for the first time.

You may be wondering how things are going for Alice, the college student I mentioned at the beginning of this article.

“I’ve been on a few dates,” she says. “It can be frustrating and feel like a lot of trial and error, but I’ve met interesting people. Even when we don’t end up being compatible, at least it helps me figure out what I do want in a relationship.”

I asked her if the issues raised in this article made her think about dating apps differently. She said, “I thought that bad behavior on dating apps was just sort of inevitable, but it’s really interesting to think about how technology could enable it, or prevent it.” Here’s hoping that dating tech will focus increasingly on the latter.

*Name has been changed.

In addition to drawing on national surveys, academic studies, and news articles, I created a survey to collect more personal feedback on the topic from friends and friends-of-friends. Their thoughts and stories make up the quotes sprinkled throughout this article. Though the group is by no means a representative sample of the US population, respondents touched on a variety of issues that I think are relevant to many people.

Operation Match materials: https://www.computerhistory.org/collections/catalog/102797880

Operation Match booklet: https://www.computerhistory.org/collections/catalog/102797881

The Strength of Absent Ties: Social Integration via Online Dating: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1709.10478.pdf

Debiasing Desire: Addressing Bias & Discrimination on Intimate Platforms: http://www.karen-levy.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Debiasing_Desire_published.pdf

The Virtues and Downsides of Online Dating: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2020/02/06/the-virtues-and-downsides-of-online-dating/

Operation Match: https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1965/11/3/operation-match-pif-you-stop-to/

The Creator of the First Online Dating Site Is Still Dating Online: https://www.vice.com/en/article/nz7e87/the-creator-of-the-first-online-dating-site-is-still-dating-online

Recruiting Women to Online Dating Was a Challenge: https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2019/04/how-matchcom-digitized-dating/586603

![]()

Check out more CHM resources and learn about upcoming decoding trust and tech events and online materials. Next up on February 18, 2021: Should We Fear AI?

Want to share your experiences and thoughts about dating apps? Keep an eye out for our upcoming polls on Facebook and Twitter.