How do you compare plagues? By which groups they most harm? By the cold calculus of body counts? Through their cultural or political weights? Or though the scars of flesh and psyche left on individual lives? If you are like me, an elder member of Generation X, then you will have lived to have seen your late adolescence and young adulthood profoundly shaped by the peak of a plague that still stalks us today—HIV/AIDS—and your middle age being actively refashioned by a companion plague—SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19—that continues to unveil its savagery. The differences and the similarities between these two overlapping plagues are both haunting. COVID-19 has been a much faster killer in the US than has AIDS. While AIDS has taken over 700,000 lives here since the end of the 1970s, it has taken COVID-19 less than two years to rob us of nearly 600,000 of our neighbors. With both plagues, the most devastated group has been Black men. There is nothing inherent about the bodies of Black men that accounts for this fact. Rather, it is a testimony to structural racism.

With HIV/AIDS, an additional and defining factor was homophobia. Those who have been infected with HIV and have died from AIDS are primarily gay men. At the heights of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, it was enormously consequential that much of officialdom—elected officials, business leaders, media and press, cultural and religious figures—were openly, even officially, homophobic. The delay and inaction that homophobia enabled put the plague on the path by which it would claim so very many and remain so persistent today. The extent of official homophobia and its consequences for the HIV/AIDS epidemic are chillingly illustrated by recently recovered recordings of White House press briefings from the first half of the 1980s, with laughter and crude jokes accompanying questions about AIDS.

Reagan Administration's Chilling Response to the AIDS Crisis (Vanity Fair)

October 2, 1986 memorial for AIDS activist Diego Lopez. Fred R. Conrad/New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/01/health/aids-day-photography-1980s.html

In the 1980s, as public health and other medical officials began to see the real nature and extent of the HIV/AIDS crisis—and, with others in the gay community, worked hard to raise alarm and attention—every individual and organization faced the challenge about how they would respond to the crisis. Would they ignore, or perhaps worse, minimize? Or would they, at some risk, step out front to take compassionate action based on the best current expert assessments? The fact that AIDS disproportionately afflicted gay and BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and People of Color) communities meant that both homophobia and racism were decisive factors in the failure of so many. With the disproportionate impact of today’s COVID crisis on BIPOC communities, it is a failure of courage and compassion that we have relived.

The challenge that the AIDS crisis presented to us all was not, however, just a story of failure. It is also the story of pride: of individuals within organizations who really walked the walk, lived up to their values, and took moving and meaningful action. What follows is one of these stories of pride. It is the story of three people who, with others inside of the then-largest personal computer software company, helped make one of the first AIDS Walk fundraisers a triumph and helped set a new standard for visible corporate support for addressing the AIDS crisis and in support of the gay community. It is the story of how this company would come to publish a book of love poems, written by its employees, in the memory of two employees who had died of AIDS, and as a fundraiser for AIDS care.

Lotus poster. Credit: Collection of CHM, 102640074

The company in this story is the Lotus Development Corporation. Founded and headquartered in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1982, Lotus is most commonly remembered for its spreadsheet, Lotus 1-2-3. 1-2-3 was the dominant spreadsheet on the market into the 1990s, rocketing to success with the spread of the IBM PC and IBM PC-compatible personal computers. In 1995, on the success of 1-2-3 and the collaboration and email software Lotus Notes (created by CHM Fellow Ray Ozzie), IBM acquired Lotus for $3.5 billion in a hostile takeover.1

Mitch Kapor, center, in early 1980s at a Computer Museum event for Danny Hillis’s Tinkertoy Computer. Collection of CHM: 102630799

Mitch Kapor, the founder of Lotus, is, appropriately, the first of the three characters in this story of Lotus’ stepping up to the challenge of the AIDS crisis. Kapor, born in 1950, had shown an early talent for mathematics, skipping ahead in early grades, and gaining unusual access to computers as a student. As an undergraduate at Yale in the late 1960s, he developed his own major, combining computing and linguistics, and jumped into the counterculture with both feet. Working as a professional disk jockey and then as a mental health counselor in a hospital, Kapor re-connected with computing as commercial personal computers appeared in greater numbers starting in 1977. Soon, he had purchased an Apple II, started programming in BASIC, and began developing commercial software at the very beginning of the personal computing software industry. In a few short years, working in partnerships and with software publishing contracts, Kapor brought a financial analysis program, a spreadsheet graphing program, and presentation software to market. The financial windfall from this early participation left him, in 1982, with $600,000. He kept $300,000 as a nest egg—figuring he could live off of it for a decade if need be—and spent the other half on starting his next effort in software: Lotus.

While Kapor’s focus on building a better spreadsheet and aiming for the IBM PC market brought him a quick venture investment from Ben Rosen, another of his primary intentions for Lotus received much less attention. Kapor wanted Lotus to be a different kind of company. He wanted it to be explicitly values-led and politically progressive. He wanted it to respect and welcome outsiders and to be an environment where “bad employees” like himself could thrive. As he recalls in his 2004 oral history for the Computer History Museum, “We created a very progressive corporate culture ... the woman I hired as my office manager [Janet Axelrod] was a political radical ... who needed a job, and I was more comfortable hiring other oddball people because I felt more comfortable with them ... We did all of this outrageous stuff that I’m extremely proud of.”

In a sense, the progressive corporate culture blossomed under the cover of the mindboggling success of 1-2-3. Lotus went from $0 in revenue when it started up in 1982 to $53 million in sales during 1983. In 1984, sales jumped to $156 million and Lotus was the largest personal computer software company in the world: larger than Microsoft, Ashton-Tate, WordPerfect, Borland, MicroPro, Aldus, VisiCorp, Software Publishing, and Adobe.2 With this astonishing success and profitability, no one inside of Lotus or without objected to the progressive moves that seemed “outrageous” in comparison to US corporate culture more broadly. Kapor explained in the 2006 oral history, “We had a corporate values statement. Usually corporate values statements are bad for morale because you do it and people realize this is not the reality … Managers’ bonuses were tied in part to how well they were rated by the people who worked for them, embodying the corporate values … they did not get their bonus unless they live up to our values. We gave back profits. There was an employee-run Philanthropy Committee … We had very serious diversity efforts ongoing. We had a very diverse workforce …We adopted the Sullivan Principles and wouldn’t sell into South Africa. We had a very egalitarian kind of culture, based on respect and fairness. I’m really proud of that.”

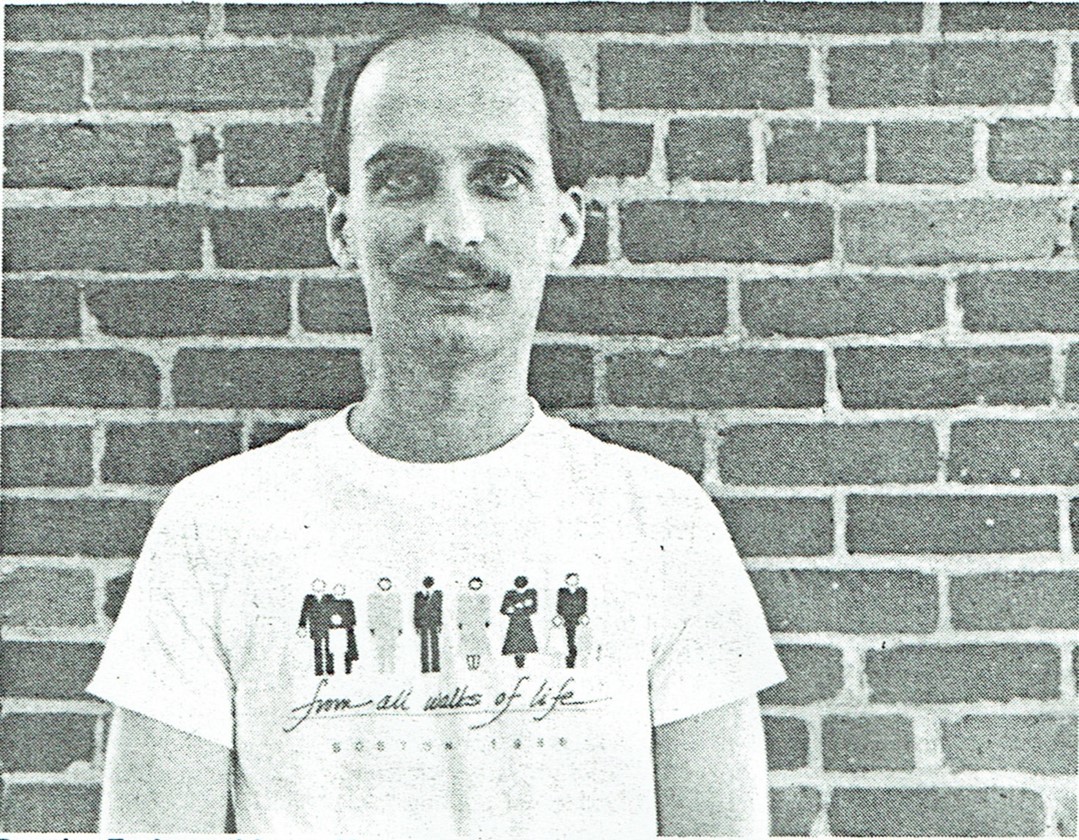

Matt Stern. From South End News, May 22, 1986

The diverse workforce that Lotus was creating for itself was the decisive factor in the appearance of the second character in our story of pride in facing the AIDS crisis at Lotus. Matt Stern, like Mitch Kapor, displayed a youthful talent for mathematics.3 It was as an undergraduate at MIT from 1978 to 1982 that Stern first encountered computers and found that he had an aptitude for programming. His college summers were filled with programming jobs for large financial and aerospace firms. One of them even paid for him to have a terminal and dial-up modem installed in his dorm room so he could continue to support his projects during the academic year. By graduation, he had landed a job with a financial software company in Boston.

As Lotus got up and running in Cambridge, Stern was contending with some uncertainties in his new life post-MIT. On one side, he had doubts about where his firm was heading and its prospects. On the other side, he was figuring out how to live his life as a young gay man, with the prospects of living out of the closet at home and at work against the bleak landscape of official homophobia in America. The professional opportunities for a talented software developer were, however, the opposite of bleak, and Stern soon took a call from a headhunter who had been hired by Lotus to help them staff up.

In 1983, with Lotus 1-2-3 announced and just about to ship, Stern found himself in the Lotus lobby waiting to be called in for his interview. “I remember watching the receptionist, Elaine Yeomelakis, handle the calls,” he recalled in a 2021 oral history with the Computer History Museum. “She was this really sweet, sweet person. And on the bulletin board was a copy of an article from the Boston Business Journal, I think, profiling Chris Morgan, who was a vice president at Lotus, who the article said was openly gay, and how noteworthy that was to have a senior executive at an up-and-coming Boston-area company be out as a gay man. That got my attention.”

Attracted by the diversity of Lotus, Stern signed on as Lotus employee number 107. During his first week, he—along with everyone else—helped 1-2-3 to quite literally get out the door: “… they needed all hands on deck to pack the boxes … we were that small that it was, you know, everybody stop what you’re doing, come over, and let’s get this product shipped.” Soon after, Stern joined Ray Ozzie and Barry Spencer in a small Lotus office in Littleton, Massachusetts. There, the trio ensconced themselves to create Lotus’ next big product, Symphony, that combined spreadsheet, word processor, graphing, database, and communications.

Freada Klein in 1979 in an Alliance Against Sexual Coercion picket. Photo by Ellen Shub.

As Lotus rose on the success of 1-2-3 to become the largest personal computer software company in 1984, the third of our three characters arrived on the Lotus stage: Freada Klein. Klein was recruited to join Lotus fresh from her doctorate at Brandeis, where she had continued her pioneering work in identifying and combating workplace sexual harassment.4 At Lotus, she took on the role of Director of Employee Relations, Organizational Development, and Management Training. Her charter was quite explicitly to make Lotus the most progressive employer in the United States. In many moves she took in service to that challenge, Klein created a Diversity Council that represented every dimension of difference and included representatives from, simply put, the lowest to the highest paid employee ranks.

Stern was one of the members of Klein’s Diversity Council, as well as a member of the company's Philanthropy Committee, and was now living openly as a gay man at Lotus. On a business trip to San Francisco in 1984, Stern had been upset with homophobic language used by several of his colleagues, none of whom knew that Stern was gay. When he got back to Cambridge, he wrote a letter to Janet Axelrod, explaining the effects of this kind of language on him as a gay man and urging Lotus employees to do better. Axelrod responded immediately, saying they wanted to publish the letter in the employee newsletter, but anonymously to protect him. Stern, now assured of his place at Lotus and in life, insisted they use his name. They did. He suffered no negative repercussions and gained a lot of respect from other gay employees. Indeed, Klein remembers meeting Stern during her first week on the job. She was explaining her role and her goals to everyone, and when she came to Stern, he said “Hi, I’m Matt. I’m gay. What are you going to do for gay people in the company?”

As a gay man, the growing awareness of the realities and severities of the AIDS crisis in the country had a direct immediacy and deeply personal dimension. As Stern recently explained in his oral history, “So I decided, in 1985, that the AIDS crisis was—I felt like it was getting closer to home for me, and I wanted to do something, and I started volunteering at the AIDS Action Committee in Boston, which was the one-stop place for dealing with that, dealing with AIDS at that point. It was the umbrella group for that. There weren't too many other groups at that point.” Klein, who was friends with Stern inside and outside of Lotus, was also active with AIDS Action. On July 25, 1985, the American movie star Rock Hudson announced that he was dying from AIDS. (He would succumb on October 2.) Hudson’s announcement was an important event in the history of HIV/AIDS, marking a change in public awareness as well as media coverage. Three days later, on July 28, 1985, the AIDS Project Los Angeles—a HIV/AIDS service organization founded in 1983—held an “AIDS Walk” fundraiser. In the publicity following Hudson’s announcement, the Walk was unexpectedly successful. 4,500 people walked a route that began at the gates of Paramount Pictures’ studio, and raised $673,000. Paramount was a corporate sponsor for the Walk, and remains so today, with the LA AIDS Walk still leaving from its gates. This first AIDS Walk was a huge fundraising boost for service organizations in the region, and an important opportunity for public visibility and activism.5

The first AIDS Walk, departing from the Paramount gates. Photo by Paramount. https://www.larchmontbuzz.com/featured-stories-larchmont-village/paramount-pictures-supports-aids-walk-los-angeles-for-the-35th-year/

Across 1986, the AIDS crisis only worsened. For Lotus, the boom continued. 1-2-3 was propelling the firm toward nearly $400 million in sales, keeping its position at the top of the chart of the largest personal computer software firms. For AIDS Action, they looked to the success of the first AIDS Walk in Los Angeles and began to plan their own for the late spring. As the organizers with AIDS Action began to contact established Boston-region firms about possible corporate sponsorships, they found themselves getting absolutely nowhere.

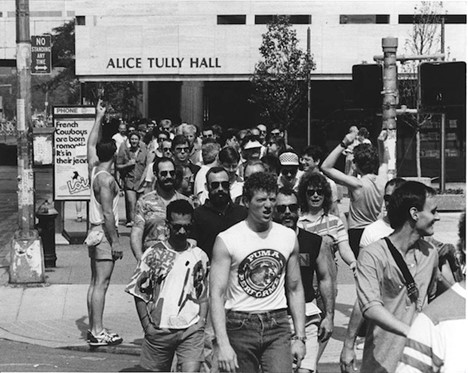

On May 18, 1986 an AIDS Walk took place in a second US city: New York. The New York AIDS Walk, organized by the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, matched the success of the Los Angeles Walk. 4,500 walkers gathered in Central Park, and raised $710,000. Mayor Koch and Governor Cuomo both made appearances, and business sponsors included both the Village Voice newspaper and The Saint nightclub.6

The first AIDS Walk in New York City. Photo by Gay Men’s Health Crisis.

Back in Boston, Stern attended an AIDS Action meeting where the organizer for the planned Boston AIDS Walk, Elizabeth Page, let everyone know what a difficult time they were having attracting corporate sponsors. In New York, the Voice and The Saint were primarily local businesses for whom the gay community was indispensable. In Los Angeles, Paramount had quietly shown that a public company could walk the walk. But in Boston, the established corporate community had not budged. Back at Lotus, Stern took the need to the Philanthropy Committee at Lotus: “I just came back and I said, you know, ‘I hear that the walk for AIDS in Boston needs a corporate sponsor, and is it something that Lotus would consider?’”

Klein immediately took up the idea. She called around to contacts at some of the most progressive companies in the country. None of them had yet sponsored an AIDS Walk or publicly supported HIV/AIDS service organizations. They warned Klein that it was too dangerous. You would lose shareholders. You would lose customers. Your employees who walked or participated would be jeopardized. There were just too many red flags. Klein, who had the explicit charter to make Lotus the most progressive employer bar none in the US, listened to the advice, and decided not to take it. Lotus should sponsor the Boston AIDS Walk.

Kapor agreed. For a decision like this, to publicly support the AIDS Walk as a corporation, Kapor explains that he and his colleagues “used their own radar.” What others might think or do as a result of Lotus’ action “mattered less to us than it would matter to other businesses, both as a material fact and as an attitude … We wanted to do the right thing, and it was an independent value, not to do with the commercial success of the business.”

Matt Stern addresses the first Boston AIDS Walk. Credit: Collection of CHM, 102792233.

Stern and his Lotus colleagues walk in the first Boston AIDS Walk with Lotus banner. Credit: Collection of CHM, 102792233.

Given the size of Boston relative to Los Angeles and New York City, the success of the Boston AIDS Walk on June 1, 1986 was extraordinary. 4,000 people walked to the Boston Common, raising $500,000. Governor Dukakis and Mayor Flynn both appeared.7 Not only was Lotus the only corporate sponsor, but its early gift of $10,000 to the Walk funded all of the organizational costs to make the Walk a success.8 Stern, who addressed the crowd of walkers on the Common from a stage he shared with the politicians and other notables, proudly walked with his coworkers behind a large Lotus banner. The crowd also sang Dionne Warwick’s 1985 hit "That’s What Friends Are For," which has been the Boston AIDS Walk’s anthem to this day. For Lotus, there had been no danger in its support of the Walk. Its growth continued. The press that it did receive was only positive. The contribution to the Lotus’s culture by walking the walk was immeasurable.

It was not long after the Walk, however, that the three people who had been so important to Lotus’s involvement would be gone from the firm. In July 1986, Kapor stepped down from his position at Lotus, that of chairman of the board, leaving his successor Jim Manzi as CEO and Chairman. He was 35 years old. Klein left Lotus the following year, creating her own consultancy to work with firms on issues of bias and discrimination. Klein and Kapor married in the 1990s and, among many other things, continue to work on redefining what technology companies can and should be through their Kapor Capital and Kapor Center. Stern, after continuing his work on Lotus Symphony, left Lotus in 1988 to pursue AIDS activism fulltime.

Despite these notable departures, Lotus’s corporate culture was strong enough that its commitment to prominent corporate support for AIDS support groups did not wane. In 1990, a set of Lotus employees created an unusual and touching fundraiser for HIV/AIDS causes: A book of poems. Dedicated to the memory of two Lotus employees who had died from AIDS, the book With Love, Lotus was primarily filled with poems on the theme of love penned by Lotus employees. The book was the result of several years effort, and the project was carried out as part of Lotus’s Philanthropy program. Not only were company resources used to produce the book, but Lotus used its sales and marketing channels to promote it, and its fulfillment infrastructure to provide it.9

With Love, Lotus, 1990. Collection of CHM: 102722067.

In the book, Jim Manzi, Lotus’s CEO, wrote “The problem of AIDS is one of health, education, prejudice, and fear. Responses to the epidemic require courage and creativity … I would like to congratulate everyone who contributed to With Love, Lotus . May their work be as inspirational to you as it is to me.” Nori Odoi, one of the figures behind the book project, wrote in an introduction, “The proceeds of this book are dedicated with Love—love for those battling a disease that our technology has not yet conquered. It is a disease that touches all our lives, but some more terribly than others. We honor their struggle and their courage … May a cure for AIDS be found soon.” It was the presence of this book in the collections of the Computer History Museum that inspired this blog. You can read it here.

Through a broad coalition of groups and individuals—established AIDS organizations like those supported by the early AIDS Walks along with new movements like ACT UP—successful pressure was put on government and corporations that resulted in HIV/AIDS treatments that, for those that have access, make living with HIV/AIDS a commonplace. But HIV/AIDS is still very much with us. There are some 1.2 million people in the US with HIV today, and over 150,000 do not know they are infected. Worldwide, there are 38 million people living with HIV, with about 21 million located in Eastern and Southern Africa.10 There is yet no vaccine for HIV. With this, AIDS Walks continue to this day in many cities and towns around the world. The Los Angeles AIDS Walk still begins at the Paramount gates. The Boston AIDS Walk still features "That’s What Friends Are For."

This year, the creator of one of the new mRNA vaccines for COVID-19, the Cambridge-based Moderna is a corporate sponsor for the Boston AIDS Walk.11 Moderna is putting two potential HIV vaccines into clinical trials during 2021, built using the same mRNA technology as their COVID vaccine.12 If mRNA technology is successful in creating effective vaccines for both COVID and HIV, it will represent one of history’s greatest successes for public investment in science and technology.

Read the full oral history interview with Matt Stern here.

Read the full oral history interview with Mitch Kapor here.

For information about the current work of Freada Kapor Klein and Mitch Kapor, visit https://www.kaporcenter.org/ and https://www.kaporcapital.com/

Make sure to look out for an AIDS Walk happening near you.