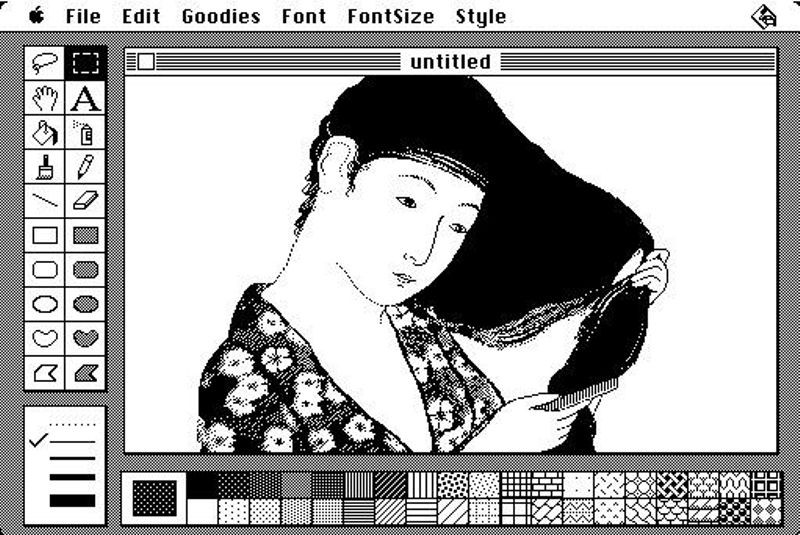

Early MacPaint drawing by Susan KareCredit: Apple, Inc.

The Apple Macintosh combined brilliant design in hardware and in software. The drawing program MacPaint, which was released with the computer in January of 1984, was an example of that brilliance both in what it did, and in how it was implemented.

For those who want to see how it worked “under the hood”, we are pleased, with the permission of Apple Inc., to make available the original program source code of MacPaint and the underlying QuickDraw graphics library.

Note: This material is Copyright ©1984 Apple Inc. and is made available only for non-commercial use.

MacPaint is the drawing program application which interacts with the user, interprets mouse and keyboard requests, and decides what is to be drawn where. The high-level logic is written in Apple Pascal, packaged in a single file with 5,822 lines. There are an additional 3,583 lines of code in assembler language for the underlying Motorola 68000 microprocessor, which implement routines needing high performance and some interfaces to the operating system.

MacPaint version 1.3 source code (5 files, 67.8k)

QuickDraw is the Macintosh library for creating bit-mapped graphics, which was used by MacPaint and other applications. It consists of a total of 17,101 lines in 36 files, all written in assembler language for the 68000.

QuickDraw source (37 files, 180.4k)

MacPaint was written by Bill Atkinson, who was a member of the original Macintosh development team. He based it on his earlier LisaSketch (also called SketchPad) for the unsuccessful Apple Lisa computer, so he originally called it MacSketch. He started work on the Mac version in early 1983.

Atkinson also created Quickdraw first for the Lisa, as LisaGraf. Andy Hertzfeld, another key member of the team, considers QuickDraw “the single most significant component of the original Macintosh technology” in its ability to “push pixels around in the frame buffer at blinding speeds to create the celebrated user interface.”²

SketchPad used menus to select patterns and styles to draw with, but Bill replaced them with permanent palettes at the bottom of the screen, and added another prominent palette on the left that contained drawing tools.

One of the problems with many early graphics programs was that as you dragged a shape or image across the screen, it had to be erased from its old position before being redrawn, which caused a distracting flicker. Bill eliminated the flicker by composing everything in a hidden memory buffer, which was then transferred to the screen quickly when it was completely ready.

Around April 1983, Bill changed the name from MacSketch to MacPaint, and starting adding new features almost on a daily basis: The “Fat Bits” mode magnified screen areas so individual pixels could be edited. The “Paint Bucket” tool identified and filled closed areas with a pattern. The “Lasso” tool selected non-rectangular shapes. He even wrote an elaborate character-recognition routine to turn pixilated characters back into text, but in the end removed it because he wanted MacPaint to be used as a great drawing program, and not as an inadequate word processor.

In writing MacPaint, Bill was as concerned with whether human readers would understand the code as he was with what the computer would do with it. He later said about software in general, “It’s an art form, like any other art form… I would spend time rewriting whole sections of code to make them more cleanly organized, more clear. I’m a firm believer that the best way to prevent bugs is to make it so that you can read through the code and understand exactly what it’s doing… And maybe that was a little bit counter to what I ran into when I first came to Apple… If you want to get it smooth, you’ve got to rewrite it from scratch at least five times.”¹

MacPaint was finished in October 1983. It coexisted in only 128K of memory with QuickDraw and portions of the operating system, and ran on an 8 Mhz processor that didn’t have floating-point operations. Even with those meager resources, MacPaint provided a level of performance and function that established a new standard for personal computers.

There are many wonderful anecdotes about the original Macintosh team collected and preserved by Andy Herzfeld at www.folklore.org. Here, with Andy’s permission, are condensed versions of a couple of interesting ones about Bill Atkinson:

A reporter asked Steve Jobs, “How many man-years did it take to write Quick Draw?” Steve asked Bill, who said, “Well, I worked on it on and off for four years.” Steve then told the reporter, “Twenty-four man-years”. Steve figured, with ample justification, that one Atkinson year was the equivalent of six ordinary programmer years.

When the Lisa team was pushing to finalize their software in 1982, project managers started requiring programmers to submit weekly forms reporting on the number of lines of code they had written. Bill Atkinson thought that was silly. For the week in which he had rewritten QuickDraw’s region calculation routines to be six times faster and 2000 lines shorter, he put “-2000″ on the form. After a few more weeks the managers stopped asking him to fill out the form, and he gladly complied.

MacPaint development was taken over by Claris, a software subsidiary of Apple created in 1987. The last version was released in 1988, and it was discontinued in 1998.

After years of designing software tools to empower other creative people, Bill Atkinson shifted focus to his own artistic creations. He is the proprietor of “Bill Atkinson Photography”, www.billatkinson.com, which celebrates the beauty of nature.