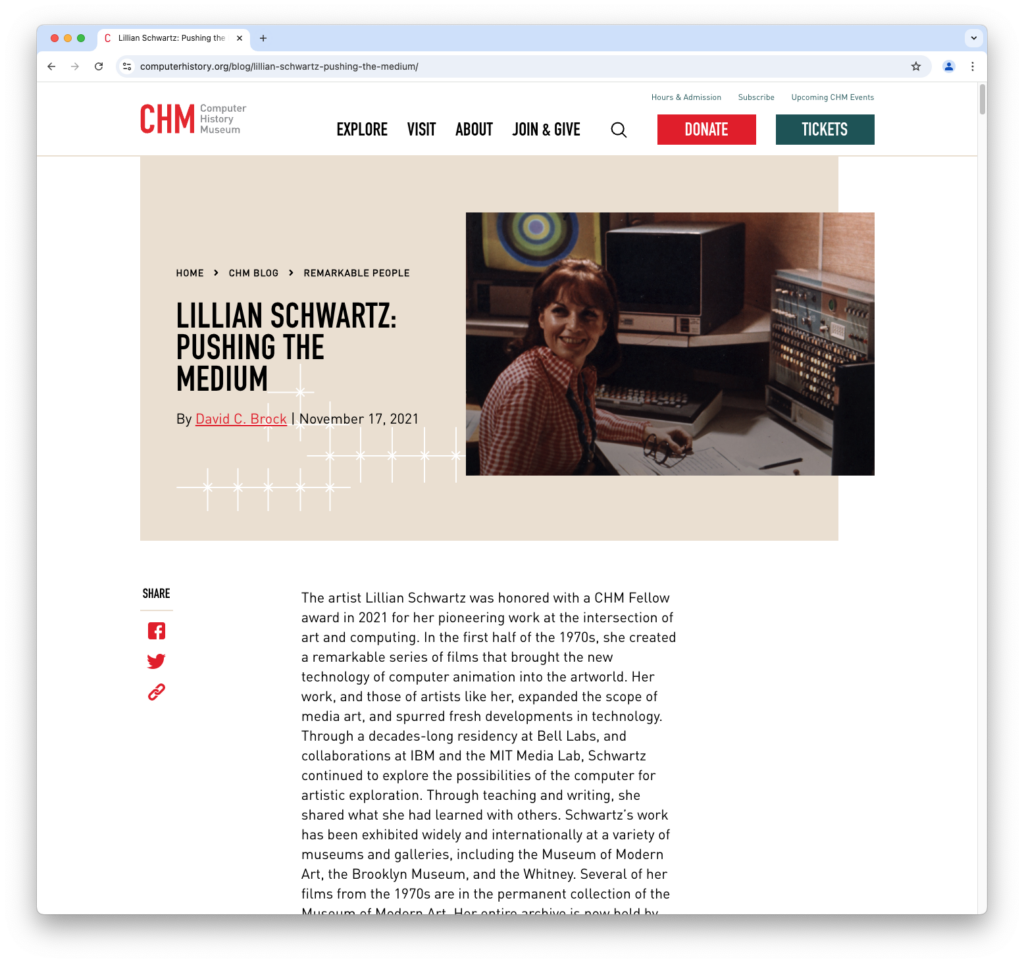

From her childhood, Lillian Schwartz was a ceaseless artist. Indeed, she began her oral history interview with the Computer History Museum with early childhood memories of drawing: drawing with sticks in dirt, and with chalk on sidewalks. When I visited her in August 2021 at her apartment in New York City in connection with her selection as a Fellow of the Museum, she was again drawing, inking fresh work that another artist friend was eager to animate using computers in a collaboration.

Matthew Cavenaugh Photography.

Between these points of first experimentation with drawing, and her continued practice of it for nearly nine decades, Schwartz enjoyed a life in art characterized by continual change and exploration. Her early embrace of the digital computer, and its capacities for generating and manipulating images, as an artist’s tool was key, in her estimation, to this continual unfolding of inspiration and possibility. Schwartz’s accomplishments in creating very early computer animations and incorporating them into a series of astonishing art films in the 1970s, made her what—as noted in Schwartz’s New York Times obituary—historian and art critic Hannah Stamler called “a pioneer of the form” of “digital imagery” itself.

Schwartz pursued the many twists and turns of the digital computer, with all of its dramatic and rapid evolutions, as her artist’s tool through a long association with the Bell Telephone Laboratories in Murray Hill, New Jersey. There, as a resident visitor and, later, a paid consultant, from the close of the 1960s to 2002, she enjoyed the use of their computing facilities and collaboration with many and diverse researchers. In 2021, Lillian Schwartz was made a Fellow of the Computer History Museum in recognition of her trailblazing efforts at the intersection of computers and art.

Born in 1927 as the youngest of 13 children, Lillian Schwartz overcame economic hardship and bigotry, creating art however she could. She sculpted with bread dough, colored on walls, and, as mentioned above, drew in the dirt with a stick. Schwartz burst into the New York artworld in 1968 with the appearance of her multimedia, interactive sculpture “Proxima Centauri” in the now famous Museum of Modern Art exhibition, The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age. Immediately afterward, she began a decades-long residency at Bell Labs the legendary research and development center. During her long and prolific career, Schwartz created a remarkable series of art films incorporating the emergent technology of computer animation, and often scored with fresh developments in computer music. Her work has been exhibited by MoMA, the Brooklyn Museum, the Whitney, and many other museums, and her archive is now preserved at The Henry Ford.

The Computer History Museum offers a wide range of in-depth and engaging online resources about Lillian Schwartz and her art. Some of them are presented below, as an invitation to experience more of this remarkable person and her body of work.

Lillian Schwartz: Pushing the Medium is an extended essay on Schwartz’s life and career and includes excerpts from her breakthrough computer films. https://computerhistory.org/blog/lillian-schwartz-pushing-the-medium/

Lillian F. Schwartz: Pushing the Medium: Art and Technology is a three-minute section from Schwartz’s oral history with the Computer History Museum, focused on her formation as an artist before her encounter with the computer.

Lillian F. Schwartz: Journey into Computer Art is a three-minute selection from Schwartz’s oral history interview, treating journey to and work in early computer films.

Lillian F. Schwartz: Breaking Boundaries, Overcoming Adversity is a 4-minute selection from Schwartz’s oral history interview, focused to the challenges she met in pursuit of her life in art and technology.

Lillian Schwartz’s acceptance remarks from the 2021 Fellow Awards. 3 minutes.

Leading video and media curator Barbara London on Lillian Schwartz. From the 2021 Fellow Awards. 4 minutes.

Professor of contemporary art and computational media Zabet Patterson on Lillian Schwartz. From the 2021 Fellow Awards. 4 minutes.

Lillian Schwartz’s 2021 Fellow Awards event, full recording. One hour.

Technology + Art. A companion essay to the 2022 exhibit at the Computer History Museum of early computer films, 1963-1972, including selections from the work of Lillian Schwartz. https://computerhistory.org/blog/technology-and-art/

A gallery of short excerpts from the films featured in Technology + Art, including several films by Schwartz. https://computerhistory.org/playlists/technology-art/

A companion essay for the 2022 exhibit at the Computer History Museum, Music-Film-Computers. This exhibit featured editions of Lillian Schwartz’s breakthrough computer films of the early 1970s with scores by F. Richard Moore, an early computer music researcher then at Bell Labs. https://computerhistory.org/blog/music-film-computers/