Introduction by Marc Weber, Curatorial Director, Internet History Program

Contributions & Insights by David C. Brock, Marguerite Gong Hancock, Hansen Hsu, John Markoff, Dag Spicer, and Marc Weber

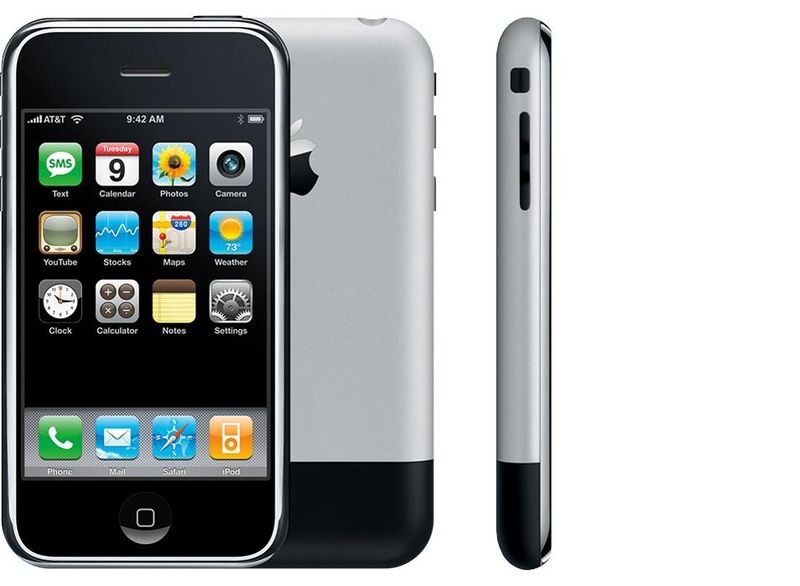

Original iPhone. Collection of the Computer History Museum, 102716304. Photo ©Apple.

By 2006 it was already clear to most people in the computing industry that the future was mobile. The cell phone was on its way to becoming the most common electronic device on earth, with over 2.7 billion users.1 Yet it was almost equally clear that the main events wouldn’t happen in Silicon Valley, or even the United States.

Since 1999 Japan had been connected to everything from mobile maps to online shopping with its own version of the mobile web, i-mode. When it came to the small but explosively growing market for smartphones, the European Symbian operating system—for which cell phone behemoth Nokia was a key partner—seemed the most likely to succeed. The profitable business smartphone market belonged to Canada’s secure, easy-to-type-on Blackberry.

The only local contender was the Palm Treo. It was a versatile smartphone based on the sleek, user-friendly Palm operating system. But it was mostly known to American geeks. Palm’s rocky business history had kept the company too small to be much of a presence in the larger world.

None of this was helped by the fact that US cell phone usage—and networks—lagged years behind other countries, and were split into two competing standards (GSM and CDMA).

For a region whose identity was so caught up with innovation, it was a smarting blow. It only seemed to confirm a 20-year local record of failed handheld computing efforts—Apple’s Newton, the Go Eo, General Magic, the Danger Sidekick, and more.

Fast forward six years. A phone that didn’t exist last time had snapped the global center of gravity for mobile development back to Silicon Valley and changed the look, feel and business model of nearly every other smartphone on earth along the way. More important, the iPhone platform and its equally new archrival Android had turned the smartphone from a niche toy into the battleground for the future of the entire connected world. The skirmish lines were no longer between browsers, but between mobile operating systems, the web itself vs. standalone apps, and even tablets vs. PCs.

The iPhone didn’t really do anything other phones or handhelds hadn’t before. It was clumsy to enter text on and not especially fast, and it initially cost $500. But looking at its ingredients is like saying that Michelin level cooking is done with the same oil and onions as diner food. It’s what you leave in or out that counts, and presentation matters.

The iPhone was announced on January 9, 2007 , in one of Steve Jobs’ many dazzling demos. It shipped on June 29. Apple sold a million of them in three months, and over a billion to date.

Millions of words have been written about what made iPhone succeed. Besides the sheer artistry of its design from software to packaging, here are five specifics:

It didn’t hurt that mobile networks had recently gotten fast enough to support full-featured web browsing on that big screen. Nor that Apple’s experience with the insanely successful iTunes store quickly translated into the App Store and the copycat Android equivalent (not to mention the services that exploded on them from rides to reviews to hookup apps). It certainly didn’t hurt that Steve Jobs was (still) at the height of his powers.

But the iPhone’s triumph took longer than many of us remember.

When I developed the Mobile Computing gallery for the Museum’s permanent Revolution exhibition over 2009 and 2010, the center of gravity for the smartphone story was still heavily outside Silicon Valley. I interviewed Japanese and Swedish pioneers, and went to London to interview the creators of market leader Symbian and the early Psion OS it was based on. The local contingent was represented by the Palm Treo, still a contender, and this newish gizmo from Apple.

In 2012 we began to research the Texting gallery in our software exhibition, Make Software: Change the World! Android—headed by Apple alumnus Andy Rubin—had joined the iPhone’s iOS as the new face of mobile. But competitors still had some cards to play. They hoped to both imitate the iOS/Android model and to address one or more of its perceived weaknesses: the dearth of practical ways to create, rather than simply consume content; poorly integrated address, calendar, to-do, and notes functions; and a lack of security, easy syncing, or connectivity with peripherals. Such features might matter more as mobile followed the iPad from phones to tablets.

But then Microsoft’s much anticipated Windows Phone 8 fizzled, taking Nokia’s smartphone market down with it along with Microsoft’s own tablet, the Surface. Palm’s legacy entered the last stages of dissolution as HP abandoned WebOS. The “iPhone killer”2 Blackberry 10 operating system tanked. The high end of the mobile world now belonged to Apple and Google—and Silicon Valley.

This year, much of CHM’s curatorial team is taking a comprehensive look at the evolution of the iPhone with the iPhone 360 project. The main techniques are oral histories, collecting software, documents, objects and more, and both public and private events. The team represents an internal collaboration between the Exponential Center, whose director Marguerite Gong Hancock is coordinating the overall effort, Hansen Hsu and David Brock of the Software History Center, historian John Markoff, senior curator Dag Spicer, and myself of the Internet History Program.

So together let’s wish the iPhone a very happy 10th birthday! In the words of the late Steve Jobs, “it’s magic.” Follow this list to retrace the journey.

SRI Mobile Van, 1977. Collection of the Computer History Museum, X1590.99.

The van where “the internet was born” was famously used for a 1977 test of the internet protocols we use today. But the van had originally been customized and filled with high-tech equipment in 1973 for fundamental research into mobile, packet-switched radio networks. These are the basis of today’s mobile data services.

Catalog Record | SRI Mobile Van

Celebration Video | 30th Anniversary of Internet Milestone

Contributed by Marc Weber, Curatorial Director, Internet History Program

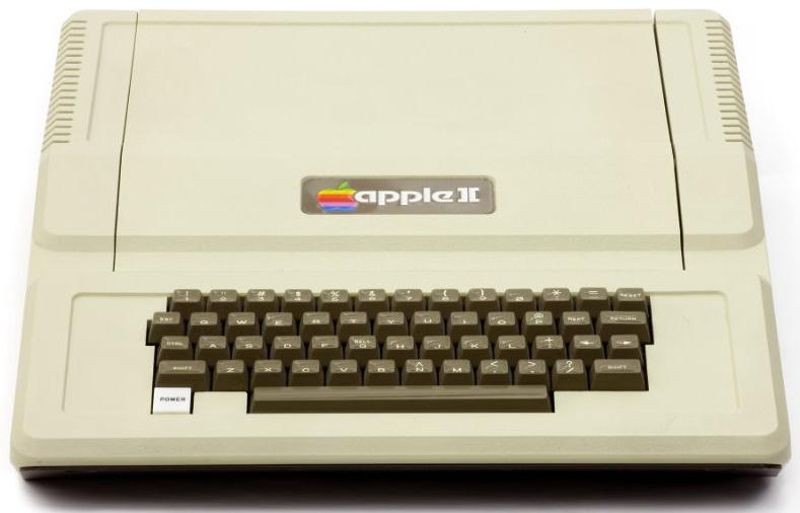

Apple II, 1977. Collection of the Computer History Museum, 102626726. Photo ©Mark Richards

Debuting in 1977, the Apple II was the product that launched Apple as a company, and brought personal computers out of the hands of hobbyists to a broader market. Like today’s iPhone, the Apple II became a successful software platform, especially for games. Also like the iPhone, the Apple II provided Apple with most of its profits, even after later products were introduced. Both led to exponential growth. Powered by sales of the Apple II, Apple reached the Fortune 500 in May 1983. Powered by iPhone, Apple became the largest company by market capitalization in August 2012.

Exhibition | “Computers for Everybody” in Personal Computers gallery, Revolution: The First 2000 Years of Computing

Oral History | Mike Markkula

Collection | Apple Computer Inc. Preliminary Confidential Offering Memorandum

Contributed by Hansen Hsu, Curator, Software History Center

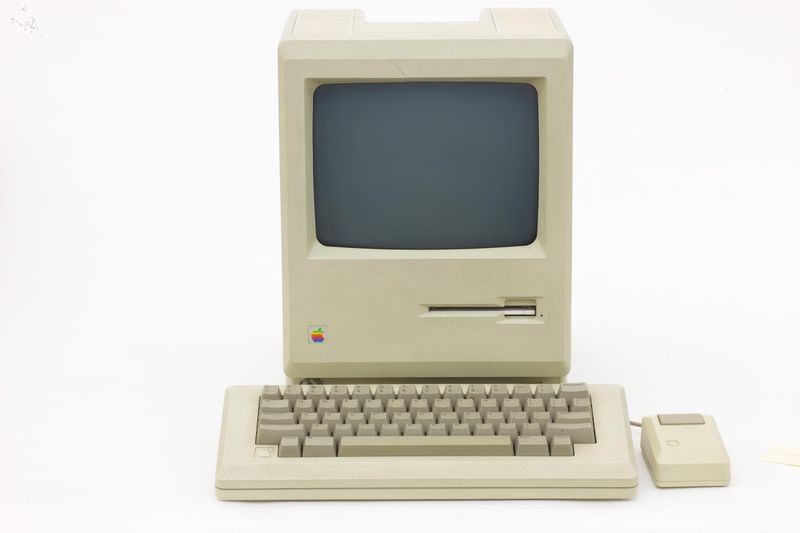

Macintosh, 1984. Collection of the Computer History Museum, 102756924, 102756926, 102756927. Photo ©Mark Richards

Just as Steve Jobs’ 2007 introduction of the iPhone transformed computing, so did his 1984 introduction of the Macintosh. Although neither product was the first in its category, both revolutionized the way users interacted with their computers. With the Mac, users could now control their personal computers graphically, with a mouse, rather than with arcane text-based commands. The Mac was copied by Microsoft Windows, and today all PCs work like the Mac. With the iPhone, users could control their smartphones directly with their fingers. iPhone was copied by Google’s Android, and today all smartphones work like an iPhone.

Article & Video | “The Very First ‘Stevenote,’” by Jonathan Rotenberg, Founder of The Boston Computer Society

Exhibition | “Saying It with Pictures,” in Personal Computers gallery, Revolution: The First 2000 Years of Computing

Contributed by Hansen Hsu, Curator, Software History Center

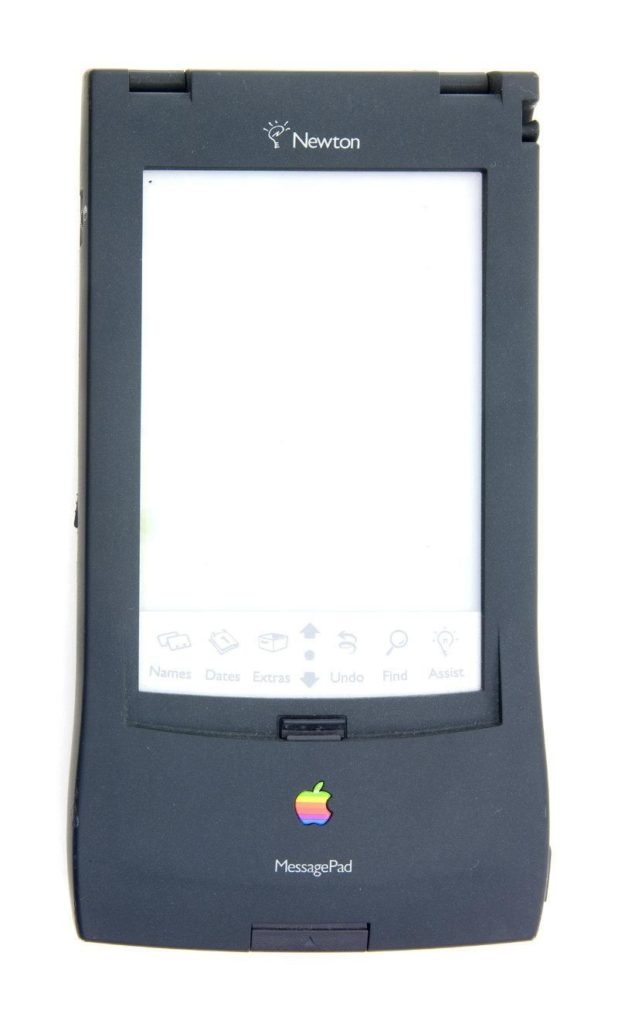

Newton MessagePad, 1993. Collection of the Computer History Museum, X2358.2002A. Photo ©Mark Richards.

The Newton MessagePad was Apple’s first pocket-size computer, released in 1993. A pen-based device, the Newton was infamous for its poor handwriting recognition, and was not a great success. Then Apple CEO John Sculley coined the term “personal digital assistant” to describe the Newton, a category later dominated by the PalmPilot. Subsequent models improved, but the product was killed by the return of Steve Jobs in 1997. Perhaps Newton’s most far-reaching legacy was its use of an ARM microprocessor. Today, ARM chips are the brains of every iPhone.

Catalog Record | Newton Message Pad 110

Exhibition | “The Pen Is Mightier Than the Keyboard,” in Mobile Computing gallery, Revolution: The First 2000 Years of Computing

Contributed by Hansen Hsu, Curator, Software History Center

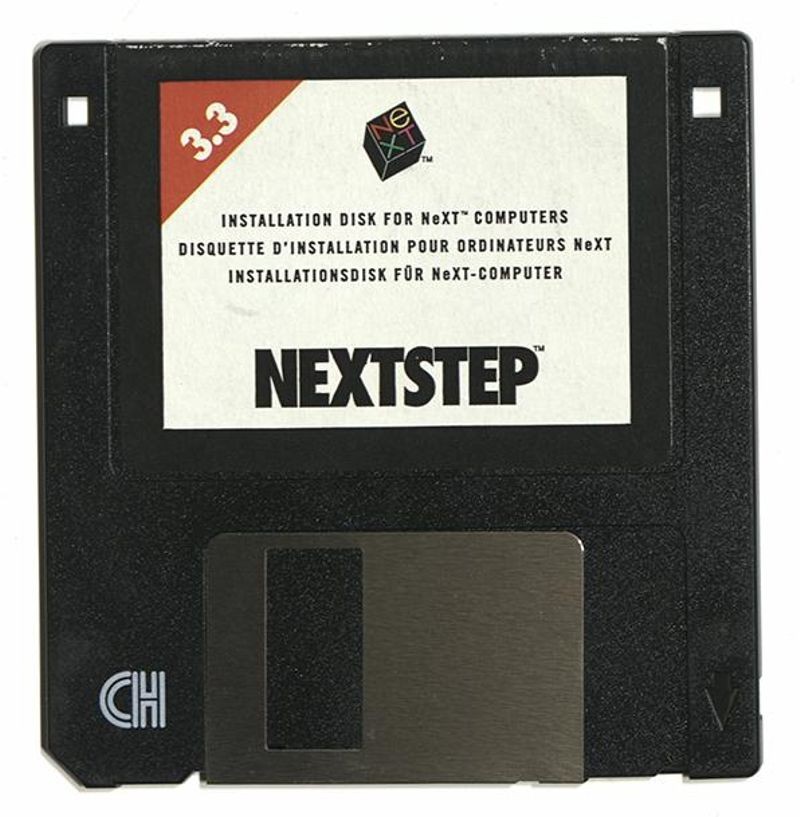

After Apple acquired NeXT in 1997, its NEXTSTEP operating system became the basis for Mac OS X and later iOS. Collection of the Computer History Museum, 102707236 and 102705564.

The iPhone OS, today known as iOS, was based on Apple’s desktop operating system, Mac OS X (2001), sharing the same kernel, drawing from the same design principles, and programmed in the same language, Objective-C. OS X itself derived from NEXTSTEP (1989), the operating system of Steve Jobs’ NeXT Computer. NEXTSTEP’s big innovation was leveraging the power of object-oriented programming throughout the system, helping programmers write applications 5 to 10 times faster. Today, the same technologies in iOS empower app developers all over the world.

Catalog Record | Mac OS X, 102776949

Oral History | Avadis Tevanian

Articles | “A Short History of Objective-C” and “NeXT: Steve Jobs’ dot.com IPO that Never Happened,” by Hansen Hsu

Contributed by Hansen Hsu, Curator, Software History Center

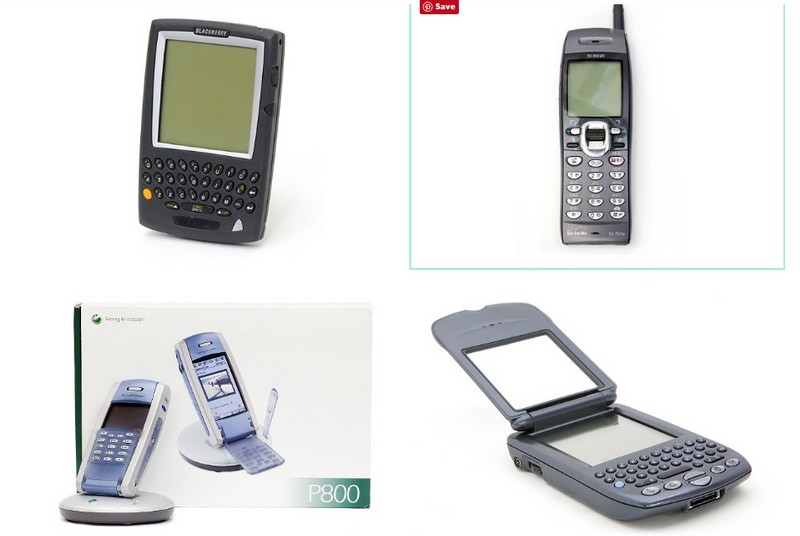

Top left to right: BlackBerry 5810 GSM wireless device and i-mode phone; Bottom left to right: Ericsson P800 phone and BlackBerry 5810 GSM wireless device

The pioneering 1993 Simon smartphone featured an innovative touchscreen but failed as a product. The first four successful smartphone lines were geographically scattered. The Ericsson P800 ran the Symbian operating system, a joint effort between Nokia and British handheld pioneer Psion. The BlackBerry 5810 was the first model to be a smartphone as well as a secure email device. i-mode phones like this one from NTT Docomo surfed Japan’s custom mobile web. The Handspring (later Palm) Treo smartphone was based on the popular Palm PDAs and the only local contender.

Exhibition | “Phones Get Smart,” Mobile Computing gallery, Revolution: The First 2000 Years of Computing

Article | “When Silicon Valley Realized It Could Put Computing in Your Pocket,” by John Markoff

Oral Histories | Charles Davies and Jeff Hawkins

Event Video | “Computing in Your Pocket: The Prehistory of the iPhone in Silicon Valley,” with Panelists: Steve Capps (Newton), Donna Dubinsky (Handspring/Palm), Jerry Kaplan (Go Corp.), and Marc Porat (General Magic).

Event Insights | “Computing in Your Pocket: The Prehistory of the iPhone in Silicon Valley,” by John Markoff

Contributed by Marc Weber, Curatorial Director, Internet History Program

“MP3 Makers & Users,” MP3 gallery, Make Software: Change the World!

The wildly successful iPod music player paved the way for the iPhone. It showed that Apple could design a successful consumer electronics product and brought together several of the team members who would later work on iPhone. It showed that Apple could be a media company. Most important, the iPod plus the i-Tunes Store showed that Apple could create a seamless end-to-end ecosystem of hardware, software, content, and e-commerce. A key selling point of the iPhone, of course, was that it was also an iPod music player...

Catalog Record | iPod, 102757290

Exhibition | “Disruptive Innovation,” MP3 gallery, Make Software: Change the World!

Contributed by Marc Weber, Curatorial Director, Internet History Program

..

Tony Fadell was a young computer designer who had worked at General Magic when he was hired as a contractor to design the first iPod. He would go on to lead the hardware development of the first iPhone and then leave Apple to found Nest, a company that designed a connected thermostat, which would be sold to Google for $3.2 billion in 2014.

Event Insights | “Computing for the Whole World,” by John Markoff

Contributed by John Markoff, Historian & Journalist

..

During 2006, the year before the iPhone was introduced, it seemed that innovation in mobile devices was beginning to slip away from Silicon Valley. Wireless computing was advancing more quickly in Europe than it was in the United States. That all changed abruptly when Steve Jobs stepped onstage at Moscone Center in San Francisco and asserted he was introducing “three revolutionary products” in one package—the iPhone.

How did iPhone come to be? On June 20, four members of the original development team discussed the secret Apple project, which in the past decade has remade the computer industry, changed the business landscape, and become a tool in the hands of more than a billion people around the world.

Event Insights | “Creating Magic: A Conversation with Original iPhone Engineers & Software Team Lead Scott Forstall,” by John Markoff

Contributed by John Markoff, Historian & Journalist

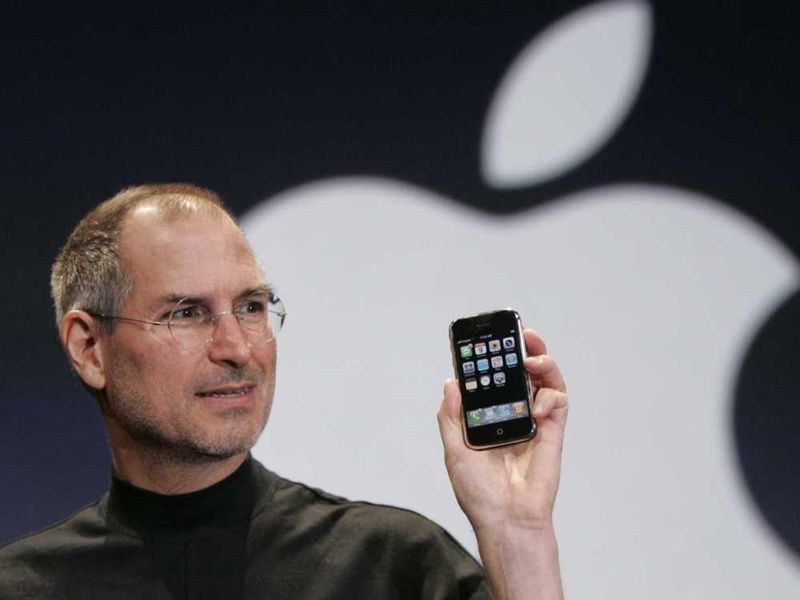

Steve Jobs introduces the iPhone. Photo genius.com.

At the 2007 Macworld trade show, Jobs announced that Apple would drop the word “Computer” from its name and become simply “Apple Inc.” The move solidified the profound shift in the company’s direction and signaled its seemingly unlimited ambition in the multi-billion dollar market for switched-on consumer products. At the Macworld show, Jobs also saved his customary “one more thing” portion of his presentation for another blockbuster announcement: the iPhone. He described it as nothing less than the re-invention of the telephone: a combination “widescreen iPod with touch controls,” a “revolutionary mobile phone,” and a “breakthrough internet communicator.”

Article | “Steve Jobs: From Garage to World’s Most Valuable Company,” by Dag Spicer

Contributed by Dag Spicer, Senior Curator

2 http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2013/09/30/blackberry-iphone-killer-verizonn4017227.html