As a software curator at the Computer History Museum, it is my job to be a content specialist in an insanely large knowledge space that I will never fully understand and to know at some high level what we have and don't have in the archives.

This work allows me to make intelligent decisions about what is being offered as historical donations and to proactively collect, filling in the gaps in the collection so that researchers have what they need to interpret the past. In this role, I was able to play a key part in collecting the Lisa source code and making it available to the public.

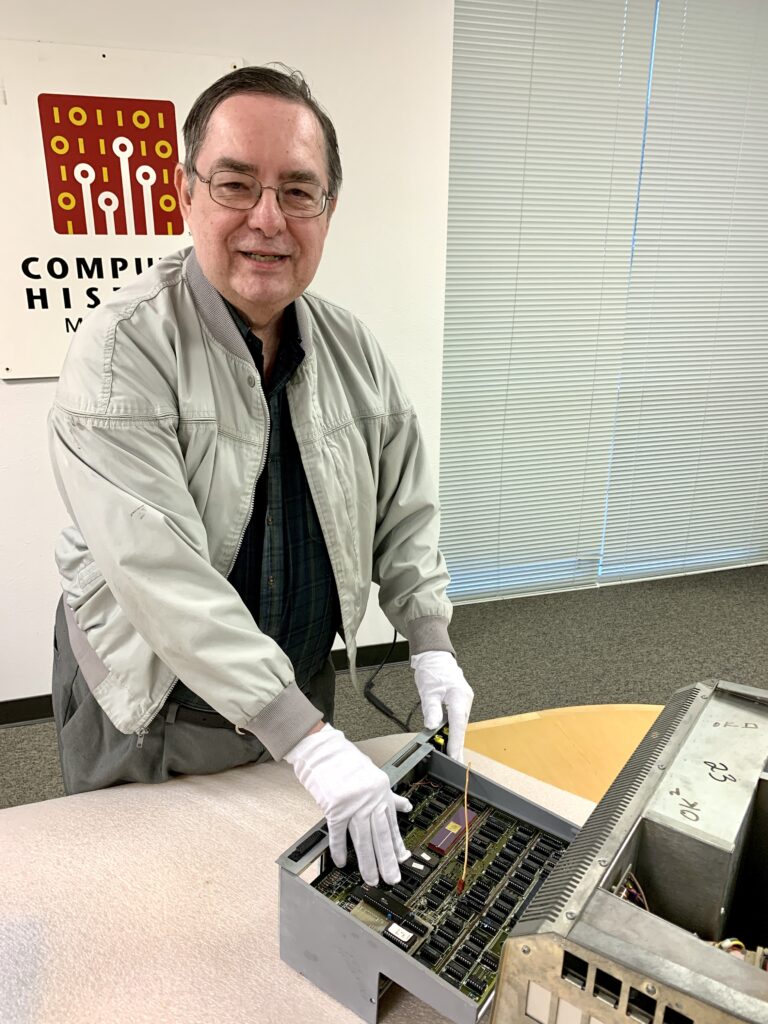

Software Curator Al Kossow with the Lisa. Kossow is the Robert N. Miner Software Curator and is responsible for collecting historical software and developing tools for reading and preserving CHM’s software artifacts.

The source code is a snapshot of an entire product, in its final form, first proposed in 1978 and shipped in 1983. The Lisa didn’t follow the usual path of Apple products. It was envisioned as a turnkey solution for business, something Apple had little experience in doing, and it was developed by management trained in the “HP Way.”

Ultimately, the UI development, system tools, and some portions of the code created for Lisa made it into the mainstream, when it was used to accelerate the development of the Macintosh.

Honestly, it’s hard to think of some new hook or anecdote that hasn’t been told literally for decades about Lisa and its place in Apple’s history. But what might surprise you is that there is still so much to discover about this time in Apple’s history. Here’s a little bit about what I have uncovered in my research and what I still hope to discover, hopefully with your help.

Back in October, 1986, long before I became a curator at the Computer History Museum, I responded to a job ad for a software engineer posted on the Usenet group ba.jobs from the legendary Al Alcorn. I didn’t know it when I applied, but Al was an Apple Fellow in a not-well-known part of the company known as the Advanced Technology Group (ATG). There were never many Apple Fellows, and they were all highly respected people who were allowed to work on whatever they wanted. When I started, for example, Lisa and Macintosh cocreator Bill Atkinson was working on a project called “Wildcard,” which became HyperCard.

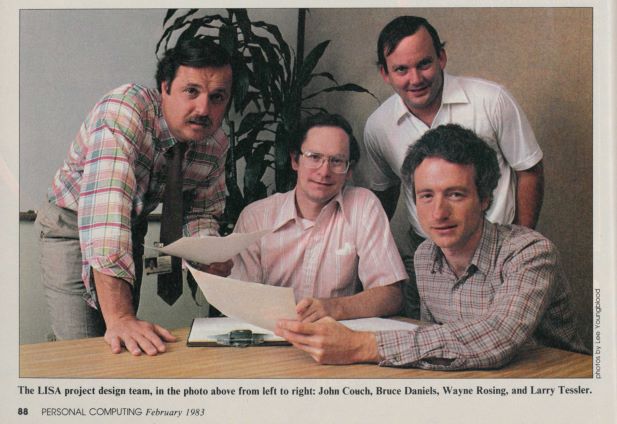

After I was in ATG for a while, I wanted to learn about its history. It turned out that after the Lisa and Mac groups merged, Wayne Rosing, general manager of the Lisa group after John Couch’s departure, ran a group of people known as the Education Research Group (ERG). When Wayne left for Sun, Xerox PARC alum and former Lisa applications manager Larry Tesler took over the group, and as its charter expanded ERG became ATG. Some of the early ATG history is included in an oral history I recorded with Larry in 2013, which you can read here.

Managers of the Lisa development group. From left to right: John Couch (VP and General Manager of the Lisa division), Bruce Daniels (software, systems architecture), Wayne Rosing (hardware, later all of Lisa engineering), Larry Tesler (applications software and libraries, user interface design and testing). Photo by Lee Youngblood. Scan of page 88 of Personal Computing Magazine, February 1983, CHM #102661079.

In the mid-’80s, ATG was supposed to be Apple’s project incubator. The plan was that as new technologies were created, they would be handed off to Product Development along with the staff. With a few notable exceptions (the people in the ATG Graphics and Sound Group) that never really happened. A whole book could be written on ATG. Maybe someone will do that someday, and the oral history I did with Larry here at CHM could help with that. In my oral histories, I try to cover topics that don’t appear in the preexisting literature.

There were a LOT of ex-Lisa people in ATG. I heard first-hand about the Lisa OS and applications from the people who wrote them. But although I tried to find someone who would allow me to see the source code, I still had not succeeded by the time I resigned from Apple and joined CHM in 2005.

When Steve Jobs gave CHM permission to release the QuickDraw source code things changed. Now, there was an approval process for getting historical Apple source code released for people to study.

I asked Chris Espinosa, one of Apple’s earliest and longest-serving employees, who I had known since the 1980s, if it would be possible to recover the Lisa source code. After some searching, he was able to find it in the source control offsite archives, and I recovered the data on one of the Macs in my software lab at CHM. The code was translated from its original format to one easier to view on a 2020s computer, and it has now been made available for you to study here.

Chris Espinosa, Apple employee number eight, was instrumental in providing CHM with the Lisa source code. Shown here, Chris with software curator Al Kossow, holding the Apple II heuristics Speechlab card at the Apple “Twiggy Mac Day” event organized by Dan Kottke at the Computer History Museum in September 12, 2013.

Looking at the code in 2023, its structure is somewhat opaque. Fortunately, the web has established worldwide instantaneous connectivity and sharing of the primary documentation sources that have been collected about the system over the decades along with functional Lisa computer emulators. As a result, I’m hoping that a dialog will start about this historical artifact and fill in some of the pieces of the Lisa story that are still missing.

In the meantime, here’s a bit of high-level Lisa software history, and some theories about why the system looks the way that it does.

The hardware and software of the Lisa didn’t spring fully formed from the work done at Apple. Unlike the Apple II before it, the company had hired engineers and management experienced in minicomputer design for the development of the Lisa Office System product.

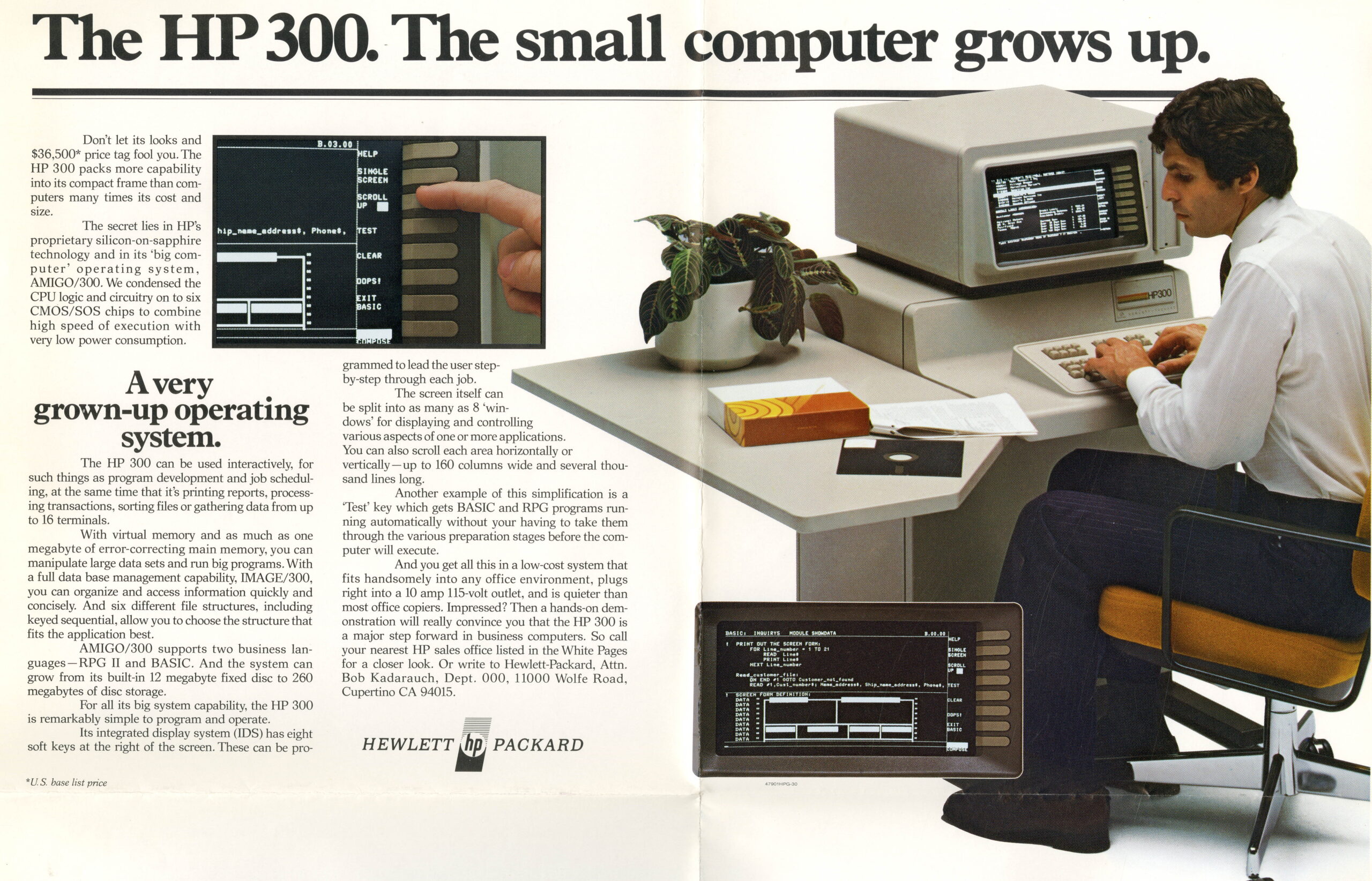

Many were from HP’s General Systems Division in the Santa Clara Valley, where the HP3000 and 300 computers were developed. They brought experience with developing operating systems and software in a high-level language and also provided a framework for the structure of the system. It is my opinion that the HP300 Amigo had a huge influence on Lisa.

The Amigo was a business minicomputer designed to compete with IBM’s System 34. It had an integrated display with application-programmable “soft switches” to the right of the wide CRT display, and internal hard and floppy disks and was announced in late 1978.

The problem was that with a base price of $36,500 the Amigo was expensive and considered a product failure. Later machines based on it (the HP250 and 260) were successful in Europe.

Unfortunately, my attempts to interview people directly involved in the engineering management and implementation of the Amigo and the Lisa have never been accepted. Hopefully, the code release will provide stimulus for new information and documentation of Lisa’s early engineering history.

Finally, two watershed events in Lisa’s development were Jobs’ visit to PARC in 1979 (read more about that here), and Rich Page coming to Apple from HP. It was Page who convinced product development to abandon its original plan to build their own custom processor and use Motorola’s 68000 microprocessor for the Lisa instead.

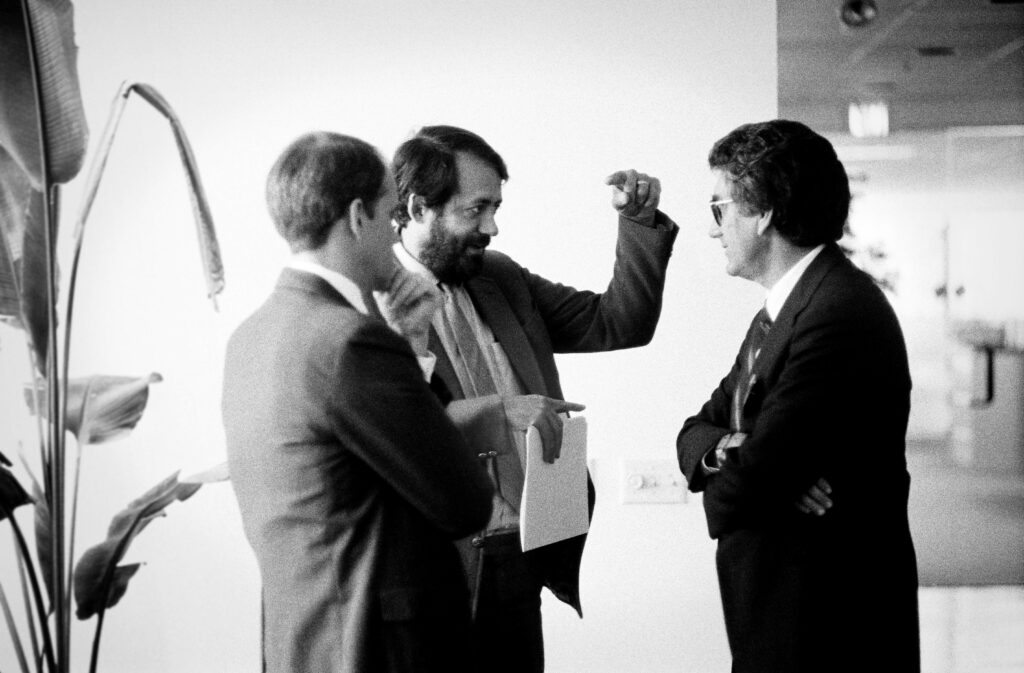

Rich Page (center) at NeXT in 1989. Page worked on the microcode for the HP3000 minicomputers before joining Apple and making the decision to use the Motorola 68000 family of microprocessors for the Apple Lisa and later the Macintosh computer. Later he co-founded NeXT with Jobs and led the hardware engineering team there. See Page’s CHM Oral History here. Photo credit: ©Doug Menuez/Stanford University Libraries

The Motorola 68000 was one of the first widely available processors with a 32-bit instruction set that ran at relatively high speeds at the time, helping to support the new graphical user interface (GUI) of the Lisa.

For those of you interested in digging deeper, there are some great sources and documentation online. Here are a few:

There are still gaps in the development engineering documents. Hopefully more will be found now that the source code is available for study. A full description of the structure of the code would be much too long for a blog post, but additional research and documentation will appear in the future. For now, have fun digging into the source code and the documentation currently online. Access the code here.

Editor’s note: In addition to recovering the source code for the Lisa computer from diskettes loaned to CHM from Apple, Al Kossow works to restore many of the unique and historic machines in CHM's extensive collection.

Learn more about the Art of Code at CHM or sign up for regular emails about upcoming source code releases and related events.