On January 6th, 2021, when the Republican crowd stormed the US Capitol building, I found out about it early on when I checked my Twitter feed. I admit I never did get back to work that afternoon; I was glued to the NBC News feed streaming on YouTube through my living room television set. My reaction was a funhouse mirror version of the Latin phrase attributed to Julius Caesar: I sat, I watched, I worried.

Just shy of a month later, on February 5th, I—another confession—lay in my bed, scanning the New York Times app before getting up as is my practice. I dove into a remarkable piece in the Opinion section about another data breach, one that told tales about the horrors of the 6th. This breach was the second time a corporate employee had leaked some of that company’s product to the Times: The consolidated geographical location information for thousands of smartphones, harvested and then aggregated from location tracking software embedded in many different apps installed on these phones that just so happened to be in Washington, DC for January 6th.

Why did the unnamed location data company have all this information? Because it is their business to harvest and aggregate this kind of data, and then sell it to whomever will pay for it. Mostly, we are told, the idea is that people will buy this location data as part of an effort to sell people something. What stories did this aggregated location data tell about January 6th? It showed smartphones in pockets, purses, and inevitable tactical gear, marching from the rally of the then-President and other Republican politicians to the US Capitol, scurrying around inside it, transforming it into a murder crime scene among other things, and then shuffling off back home.

Did the members of this crowd know that the smartphones were sending out some 100,000 location pings during and after the horrors of the 6th? How would they know that this kind of data about them was being produced, aggregated, and sold? For whom was this data about them working? Are there apps on my iPhone doing this for (or to) me? To be honest, I don’t know. I adjust my location settings to only allow sharing my geographical location data with apps that I trust, or that I want to use that won’t work without it. I run all of my cellular and Wi-Fi connectivity through another app, a Virtual Private Network, designed—I’m told, and I trust—to block out all sorts of tracking and monitoring, or, to put it differently, the creation of data about me that I don’t trust will be put to work for my benefit. Would these steps prevent location data about me from ending up in the massive aggregated data products created by location data firms, such as the eerie first data leak to the Times of 50 billion pings? Who knows?

(If you know a lot about data collection, try our KAHOOT! Challenge and join the running to win a prize; the quiz must be completed by March 23, 2021.)

Why, dear reader, would I drag you through these unsettling landscapes? It is to point out, maybe dramatize, just how few of us really know what’s going on with the data produced, aggregated, and sold about us, and to whose benefit this data actually accrues. This example of location data is but one iceberg in a dark and cold sea of private sector firms that create, gather, and sell data about us for their profit, and not necessarily—or even secondarily—for our benefit.

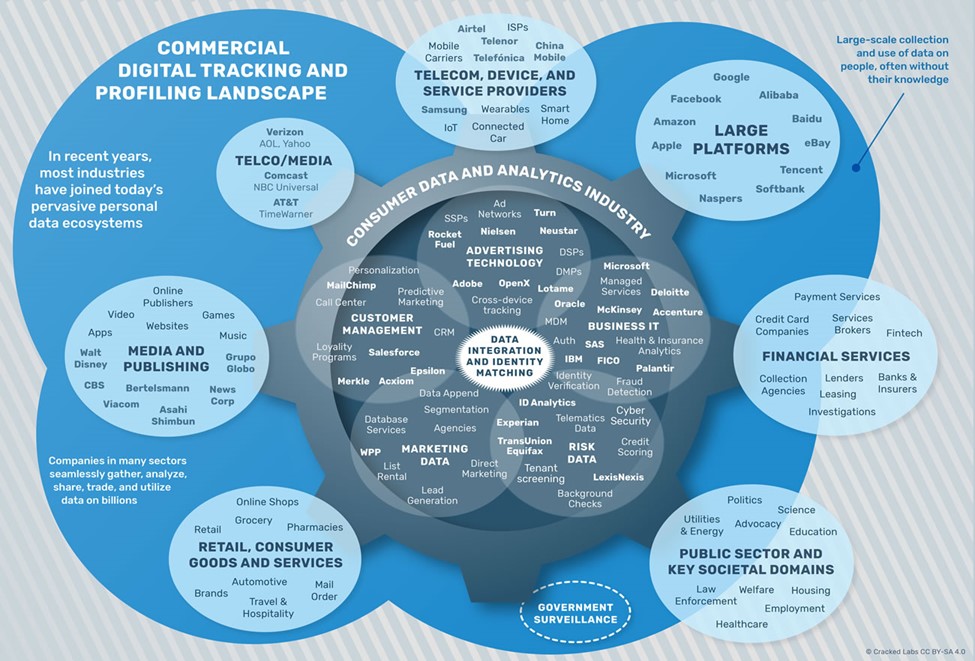

From Cracked Labs, 2017, “Corporate Surveillance in Everyday Life.”

While stories about data creation, aggregation, and use by large technology firms for their core targeted advertising businesses abound, there exists another huge, and hugely consequential, amount of similar activity around our finances: What and where we buy with credit, debit, and gift cards; If and how we use banks; How and when we pay our bills; Our use of payday lenders, car loans, and other sorts of loans. Here again we find companies that specialize in data aggregation—buying the data about you that credit and debit card companies create about your spending, buying data from banks about your activities there, etc.—and then selling this back to other financial firms so that they can make decisions about you.

The creation and processing of financial data about people is an important theme in the history computing. This IBM 405 from 1934 performed accounting calculations. https://www.computerhistory.org/collections/catalog/102645478

Perhaps the best known of these financial data aggregators are the consumer credit reporting bureaus and the company FICO, with its all-too-familiar “FICO Score” product. Your FICO Score—and if you are 18 or older in the United States, it is an extremely safe bet that FICO has one for sale about you—is marketed as a measure of your credit-worthiness, a gauge of how likely it is that you will pay back your debts with interest. In practice, the number FICO sells about you does much to determine if, and how expensively, you can access credit: The amount of interest you have to pay for a car loan, and if you can even get one, for example. This data created about you isn’t fully in your control. You don’t have a lot to say about who looks at your FICO Score, if or how your Score goes up or down, and how exactly it’s used. Both with marketing data aggregators and financial data aggregators in the US, the data produced and sold about you is put to work for the primary benefit of others. Whether or not this data in fact works for your benefit is, in the end, unclear.

An abundance of apps allows smartphone users to check their FICO Score. From https://www.quoteinspector.com/images/credit/bad-credit-mobile-application/

Indeed, the FICO Score is mutating into a kind of for-profit “social credit” scheme–moving from a measure purporting to reflect your credit-worthiness, to becoming a measure for your social worthiness, how trustworthy you are in general. It is common today for your FICO Score to be used in employment decisions about you. There are some state laws that seek to put some limits on the practice, but the exemptions are broad, and the loopholes gaping. There has been a lot of attention to China’s development of its “Social Credit System,” a very large state-run data aggregation effort to collect all sorts of data created about its citizens, and with this to assign a numerical score purporting to reflect their general social worthiness. The Social Credit Score is used in China for a variety of purposes, including employment decisions. Sound familiar?

Caption: A smartphone screenshot for an app for checking your Social Credit Score in China. From http://ub.triviumchina.com/2019/10/long-read-the-apps-of-chinas-social-credit-system/

Around the world, there are four distinct approaches to answering the question “For whom does data about people work?” These approaches were beautifully, and succinctly described in a 2018 Washington Post article by the New York University data scientist Vasant Dhar.

The first approach to data creation and use is the “US approach,” which “emphasizes moneymaking.” This is the model that you readers in the US are living with today. There are few laws, regulations, or restrictions on the ability of private firms to create data about you, and to buy and sell that data for the purpose of their profit. A second model is the “European approach,” which emphasizes laws and regulations to mitigate the harms to individuals in a system of for-profit data creation, aggregation, and sales. It is, in my view, the US model with harm-reduction laws imposed. These laws seek to protect individuals from data about them being “misused, lost, or stolen.”

A possible step in the evolution of the US approach toward the European approach is a California state law passed in 2018: the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA). The CCPA aims to give California residents some controls over the data created about them. You can’t exert control over data about you that you don’t know exists, and so the CCPA gives residents the right to know what data firms create about you, how they use it, and if they share or sell it. With exceptions, the CCPA also gives residents the right to have the data created about them by companies deleted. Further, the CCPA gives residents the right to prevent a company from selling data about them, and to non-discrimination—essentially non-retaliation—for exercising any of these new rights of control.

If the CCPA plays out as intended, it should prove an important step toward harm reduction in the US approach, moving it significantly toward the European model. The data about you will still be designed to work for the profit of others, but at least you will in principle have some controls to prevent the data about you from working against you. Nothing in the structure of the CCPA appears to fundamentally shift the model to ensure that the data about you is put to work for your interests.

The third model described by Dhar is the “Chinese approach,” which “emphasizes controlling data—and people.” The model essentially centers the state, where closely enforced rules and laws ensure that the data created about people by any organization are fully accessible to the state, and under the ultimate control of the state. In this approach, it is clear that data produced about people is put to work for the interests of the state. Whether or not putting data to work for the state also serves the interests of a particular individual is, to understate, complicated. The answer is likely partial and changing. It depends who you are, what you are trying to do, and what aspect of your life you are considering.

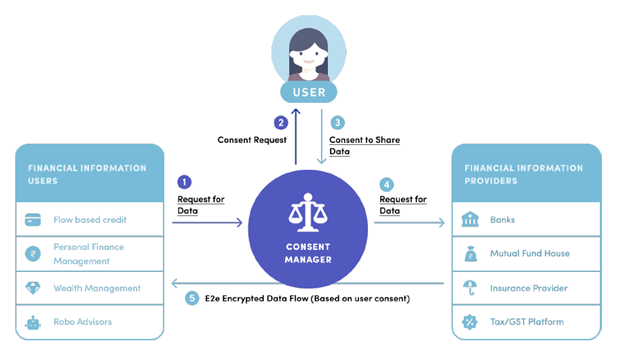

In India—the world’s largest democracy—an inventive and exciting approach is taking shape, and a fascinating new experiment is underway. As Dhar puts it, “India is treating critical digital platforms as public goods.” Through new laws, the Indian government is creating a new type of market structure for the data created about people, explicitly aimed at “data empowerment.” In the terms I’ve been using in this article, the goal is to create a computing-enabled model that ensures by design that the data about people is put to work primarily for people. Initially the market design will concentrate on finance, attempting to put financial information about an individual in service to that individual and at the control of that individual.

From “Data Empowerment and Data Protection Architecture: Draft for Discussion,” August 2020.

At the center of this new model is a novel kind of organization, the “Account Aggregator.” Aggregators are regulated, financial data intermediaries, restricted to the business of making data about individuals work for individuals. Aggregators will act as “consent managers,” acting on behalf of individuals to safely share, at an individual’s request and control, financial data about them from one organization to another in order to access some good or service. Aggregators are restricted to the business of being only this kind of data intermediary, and they cannot store any of the financial information gathered and transmitted on behalf of an individual. Data flows through the aggregator, but is not stored. For a good account of this Account Aggregator experiment, see a recent working paper by historian Arun Mohan Sukumar.

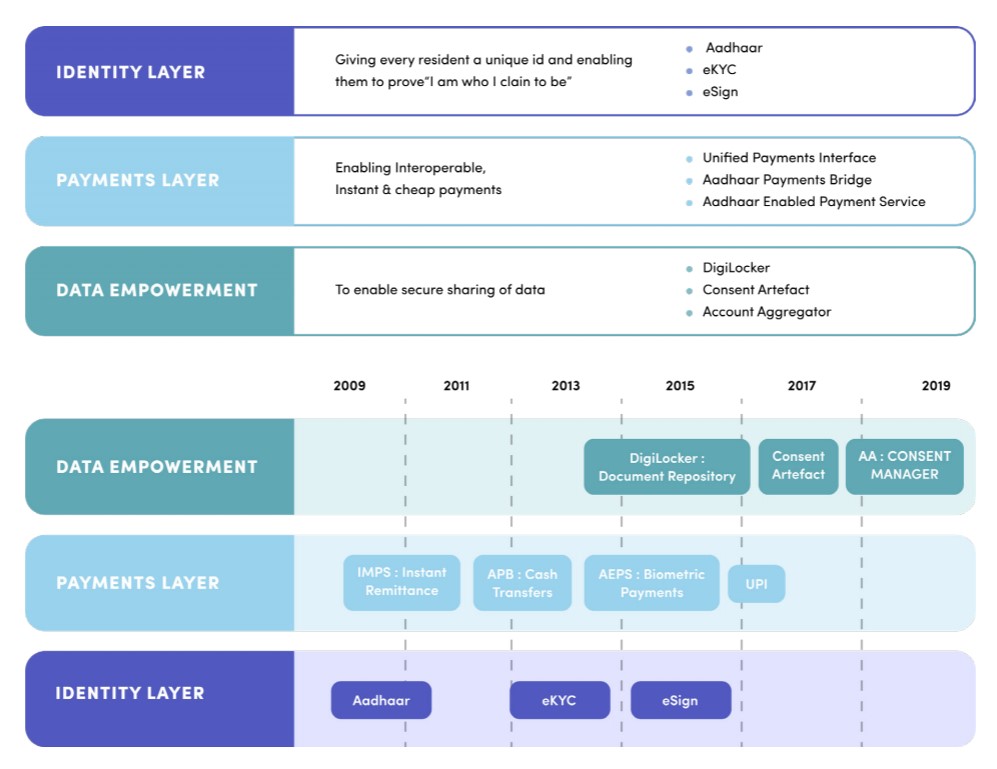

The Account Aggregators are the latest layer in a set of public sector digital technologies collectively known as the “India Stack.” The first layer comprised systems for establishing individual identity. The most prominent of these is Aadhaar, a digital identity confirmation system that provides unique identification numbers—associated with a set of biometric identifiers—for people resident in India. While there have been serious discussions about privacy and other concerns with Aadhaar, nearly 1.3 billion people in India have joined the system. The second layer added a digital payment infrastructure: a system of common protocols and services that tap into the identification layer to allow a broad range of digital payments and other transactions. The third “data empowerment” layer, in which the system of Account Aggregators resides, is in the process of construction.

From “Data Empowerment and Data Protection Architecture: Draft for Discussion,” August 2020.

One of the most prominent advocates for Account Aggregators and the entire India Stack of public sector digital infrastructure is Nandan Nilekani, a cofounder of the major India software and services firm Infosys. Recently, Nilekani articulated the vision for the India Stack and the possibilities of a the Indian model for public digital infrastructures in a major piece in Foreign Affairs. He has also advocated for the place of data empowerment in the transformation of India into what he and others call an “opportunity state:”

In the end, India’s new model of digital infrastructures as public goods depends on the underlying laws that created them, and the enforcement of these laws. That, in turn, depends on the trustworthiness of the democratically elected government of India. I, for one, will be following the Indian experiment with great interest. It is the only of the four approaches that has the design intention to ensure that data about people is put to work for people. And it is certainly true that questions of trust cannot—and should not—be avoided in any of the four existing approaches for putting the data created about people to work. We cannot avoid the necessity of asking ourselves if we can trust ourselves to do the right thing.

![]()

Read the related blog, Making Your Match: How Dating Apps Decide How We Connect, or check out more CHM resources and learn about decoding trust and tech.

Want to test your knowledge about what you just read? Try our KAHOOT! Challenge and join the running to win a prize (quiz must be completed by March 23, 2021).