Interview with Nick Hughes, architect of the M-Pesa mobile payment system

With his clipped red hair, freckled ruddy skin, and open yet no-nonsense manner, Nick Hughes could play a British army officer in the movies. But this quietly effective former geologist is the architect of the world’s leading mobile payment system, one that has changed daily life in Kenya and offers a possible glimpse into the future for many in the developing world. As readers saw in Part I of this posting, where we interviewed Maasai herdsmen about their use of mobile phones, M-PESA is the ubiquitous service that now moves over a quarter of the entire country’s GDP and holds nearly half of its people’s savings.

Today, Nick has devoted himself to development work. He is co-founder of a solar startup bringing affordable and sustainable power to the same kinds of poor and rural customers whom M-PESA freed from fears of muggings for cash and from extortionate middleman’s fees. But back when he started building M-PESA in 2004, he was working for the Corporate Affairs department of the giant British mobile provider Vodafone after leaving a similar position at BP.

His job? To fund the sorts of socially conscious, corporate “good citizen” projects that can also lend themselves to ad campaigns. At the extreme, such efforts can be cynical exercises like the limpid-eyed birds or sea turtles staring out from Chevron’s infamous “People Do” campaign. But Nick’s project would save untold wasted hours and shillings for Kenyans of all classes, and serve as a model around the world for a truly effective mobile payment system.

An obvious project was to help somehow with the direct micro-loans that had become the favored way for Westerners to directly support vendors and small business people in the global South, with hundreds of institutions emerging in dozens of countries. But how?

In the mid-2000s mobile phones were exploding in the developing world, and Vodafone owned a significant stake of the Kenyan provider Safaricom, which was expanding aggressively and fast becoming the country’s leading mobile provider. “Safari” means journey in Kiswahili, perfect for a mobile company. Nick and his colleagues decided on a relatively safe choice, a mobile system to allow micro-borrowers to service their loans without having to travel or pay big middleman’s fees. In the developed world we assume that as long as we’ve got the money, the mechanics of making payments on a loan are trivially easy, an afterthought. But where ordinary people don’t have bank accounts money transfer is expensive, time-consuming, and dangerous; making sure everything works smoothly is a big chunk of the cost of administering loans in many countries.

I was talking to Nick on a rainy September day in London, a couple of weeks before leaving for Kenya to see how the system works in practice. My colleague Jon Plutte, the Museum’s Director of Media, was directing the cheerful Cockney hired videographer in the same conference room where we had just interviewed Wikipedia’s founding publisher Jimmy Wales, whose office was upstairs. Both Wikipedia and text messaging are stories in the upcoming “Make Software” exhibit. Nick had been kind enough to round up some of the key people behind M-PESA in Kenya to talk with my wife and I when we got there.

The “Make Software” exhibit is about software that has changed people’s lives. For both stories, I was excited about interviewing not just the pioneers – the bread and butter of Web and computer history – but also the end users, and the middlemen, and in short the whole ecosystem from creator to consumer.

Nick told us about the first field trial of the micro-loan repayment system, in a market town full of traders an hour or two from Nairobi. Developed by Sagentia, a high powered consulting firm in the famed “Cambridge Cluster” of university spinoffs, it had all sorts of features custom built to anticipate every step of the loan repayment process. But then two things happened. First, the relationship with the local micro-lender went sour. More important, people in the trial started using the system in unanticipated ways. They paid personal debts to each other, and to the real surprise of Nick and his team, began using the system as a mobile wallet despite the processing fees. They said it was worth it for the security of not carrying cash.

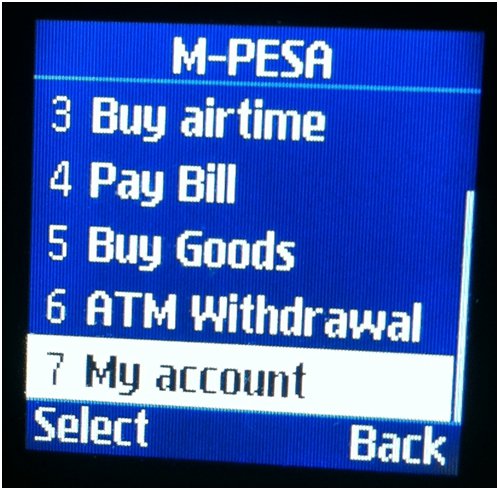

M-PESA main screen, scrolled down

Nick soon asked Sagentia to strip out all the fat in the software, all the extra screens and commands and unneeded bits and bobs related to microloans, and turn it into a pure payment system. What was left was an elegantly simple design, as spare and functional in its own domain as anything by Apple. M-PESA – pesa means money in Kiswahili – was born. With it, anybody with a mobile phone could pay anyone else. The cash would be deposited or redeemed at one of what would soon be thousands of M-PESA agents to litter the country. The system ran over SMS, the text message protocol supported by even the cheapest mobile phones.

But who’s idea was that? If you ask a person on the streets of Nairobi, he or she will tell you the key formula for M-PESA was developed by a Kenyan, who was then deprived of his rightful share by corrupt politicians. There have been newspaper articles and perhaps even a court case. The M-PESA pioneers say it’s just an instance of parallel conception at best; somebody had a similar idea and, when M-PESA took off on its own, thought he had dibs on the whole field. Such tenuous claims are common enough in the technology history trade. Few outside it realize just how usual parallel development really is, more the rule than the exception. But that’s a topic for another essay. To see whether there’s any grain of truth to this particular story will take more research.

But just as interesting is the story’s general shape: Corrupt politicians stealing from the rightful owner. This is a fault line deeply etched in the national psychology, a theme we heard over and over again, from herdsmen to government workers themselves. It’s not so different from similar memes in Italy or Russia, though with its own backstory of foreign-connected powers vs. locals thrown in as well. Still, in our very limited experience many things in Kenya seem to work as well or better than in Italy or Russia or many other countries, from passport control, to professional services like the video crew we hired, to pretty much anything to do with telecommunications.

Elegant as the final M-PESA concept was, what made it really go had far less to do with ideas than with scale, and luck, and especially with taking a big risk – both with money and credibility. In the months leading up to the service’s 2007 rollout, Safaricom spent nearly two million dollars swapping out every single customer’s SIM card for a new one with the M-PESA application built in. They created an ad campaign to educate users who had never touched a computer or an ATM machine about passwords, and security, and trusting an electronic system. The slogan was one that resonates with the millions of Kenyans who have moved to the city for work: “Send Money Home.”

Most critical of all, Safaricom built a nationwide network of an astounding 40,000 agents, all of whom needed to be vetted and trained on a system that was simultaneously being created out of whole cloth. Not to mention distributing tens of thousands of gallons of distinctive green paint to kiosks, huts, and booths from the warm beaches near Mombasa, to the flanks of Kilimanjaro and shores of Lake Victoria to the east, to the empty northern deserts that hold some of the cradles of humankind.

Naivasha wildlife and vacation home

Lake Naivasha and its city are an intersection of rich and poor in Kenya, and of old and new. The colonial past is visible here, from the gorgeous, overstaffed “Out of Africa” style resorts at the water’s edge to fancy country houses nearby. In fact, that book’s author Isak Dinesen, aka Karen Blixen, lived in the general region, and some of the movie version was filmed here by the giant freshwater lake. Under British rule the country’s only airport was nearby. Chunks of the surrounding region are still under a remnant of colonial ownership; notably the over one hundred square mile realm of an eccentric English libertine, the late Lord Delamere. While smaller than similar holdings held by a few Kenyan politicians, this is far more controversial for its ties with the past. It doesn’t help that just a few years ago the Lord’s great grandson shot and killed a poacher on that land, two years after killing an undercover game warden, and served a mere eight months in prison to the great anger of many Kenyans. The train to Nairobi no longer carries passengers, although there is talk that the new government may restore service soon, and they have already done much to improve the roads. There is plenty of work in the greenhouses that fuel Kenya’s massive export industry of cut flowers to Europe. Some is dangerous; the college-educated guide whom we interviewed on an island in the lake had worked as a pesticide sprayer for $2.50 a day until a doctor told him he had to stop or risk kidney failure.

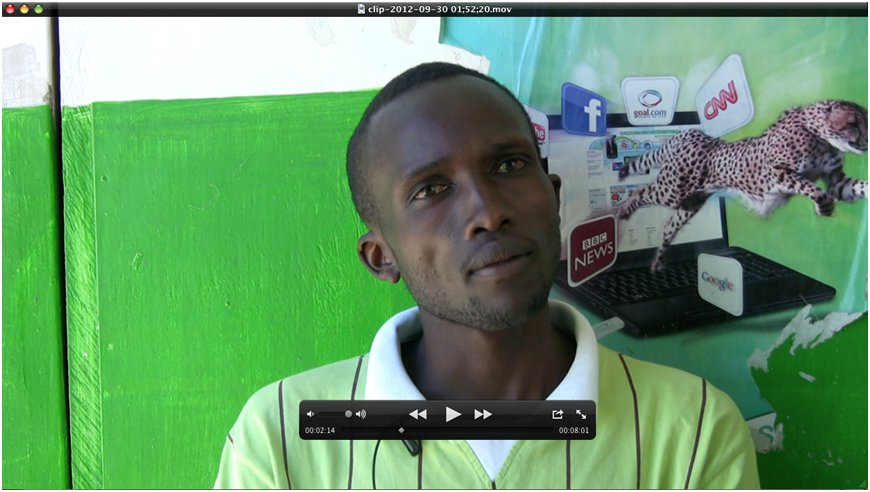

Still from video interview of Marteenie Maenah, M-PESA subagent near Lake Naivasha, in the entrance to his shop

The next morning I moved from interviewing users and creators of M-PESA to that all-important agent network. My wife Raffaella and I talked with Marteenie Maenah in the entrance of his agent’s shop in the rough equivalent of a strip mall near the lake, just outside the town of Naivasha. Only in his 20s, he’s a sub-agent to an older, full agent who can meet the various requirements including having access to over $50,000 in assets. He’s here late into the night, loading and disbursing amounts in keeping with that common $2.50 daily wage of people around here, many of whom work in the flower industry.

There’s an ATM across the alley. But Marteenie tells us that even for the less than half of his customers who have a bank account, the minimum of around $12 is more than most people want to draw out in cash. M-PESA lets them buy things in the 25 and 50 cent ranges. These could be a few minutes of airtime, or an individual packet of laundry powder, or a fresh tilapia like the ones we saw in the hands of the subsistence fisherman we interviewed the day before on the muddy shore of the lake, hippos’ eyes protruding above the surface a few tens of yards behind. Whimsical and plodding as they look, hippos can be lethally aggressive – and fast – both on land and in water.

Marteenie has been through a Safaricom training program, and he and his colleagues travel for refresher courses at least once a year. The equipment he needs is simple. Besides the shop itself, there’s only a mobile phone with the special backend Till (cash register) application loaded, one book to register customers, another to record transactions, and a strongbox. And, of course, a steady supply of cheerful green SIM and top-up cards. No computers, no modems, no printers, or copiers, or fax machines or conventional telephones. It is the true mobile office to come.

One man, fragrantly drunk at ten in the morning, keeps interrupting and telling us hard luck stories in the hope of a loan. But Marteenie says there are few real problems; mostly would-be fraudsters trying on one scheme or another. A security guard stands outside, as at any bank or ATM in Kenya. If somebody loses their phone, they call customer care to block the account. Nobody else can withdraw cash from it anyway without showing a national ID card to the M-PESA agent.

Kenyans generally perceive M-PESA as secure, and few are concerned about privacy tradeoffs as in this Safaricom Web page about mandatory registration for each SIM card

I film as he registers my wife Raffaella for a Safaricom SIM card and associated M-PESA account, taking her through each step of the five minute or so process as I had done a few days before. A few customers seem surprised to see white tourists signing up for the service. When it’s done, we try out sending money to each other’s mobile numbers – which double as M-PESA accounts – in literally just a few key taps.

The size and quality of this agent unique network is one big reason M-PESA’s success has been so hard to duplicate in other countries. Unlike the traditional Silicon Valley practice of experimenting with a business idea and scaling it up if it gets traction, something like M-PESA is more of an all or nothing proposition. You have to put in an expensive critical mass of infrastructure before you can even give the system a good try. A Kenyan sending money to his or her aged parents in the countryside won’t ask them to walk tens of miles to the nearest agent. There needs to be one around the corner, and that’s a big investment in a country of 40 million spread over an area nearly the size of France.

But there’s another secret weapon behind M-PESA’s success: Government regulators.

The third part of this series will explore the unusually entrepreneurial role that Kenya’s central bank played in fostering the system, a sharp contrast to similar efforts in other countries. It will introduce the reader to the current and former leaders of M-PESA who helped build it into the flagship and magnet for the emerging mobile startup boom centered in Nairobi.