NCR 304 salesman’s model. Gift of Albert Schott

A few months ago, the Museum was the recipient of a mystery package. Inside was a 1970’s era suitcase. Buried within was the wonderful surprise of 21 individually bubble-wrapped pieces of a salesman’s scale model of a National Cash Register 304 system. (Thank you donor, Albert Schott, for bestowing CHM with such a rare item!) As we unwrapped each piece, we noted the original adhesive had failed on a few of the disk drive doors, the reels had come unglued, the chair was in three pieces. While some might find that disappointing, CHM Collections staff considers these examples of deterioration as an opportunity to learn how to best care for the collection.

On their arrival at the Museum, most newly donated artifacts require a bit of cleaning. It’s usually simple vacuuming to lift dust or removing some sticky residue. But in the course of reviewing objects when responding to research and loan requests or for CHM’s own exhibits, we sometimes find objects that need more significant TLC—tender, loving conservation. And like all museums of excellence, CHM turns to professional conservators for help.

Honeywell Fox close-up showing broken leg

While examining the whimsical Honeywell fox (part of Honeywell’s animal sculpture series) for possible display, I determined it was time to address the breaks in three of its legs. Not doing so would mean the fox would have to remain in storage indefinitely. The fox is constructed of multiple pieces of foam, painted and then adhered with a variety of wires, diodes, processors and similar components. Unfortunately, the fox has a broken ‘hind’ leg and two broken ‘fore’ legs with the right ‘paw’ completely severed (so to speak). Decades ago, someone not trained in museum conservation, attempted repairs which did not stabilize the breaks sufficiently. In fact, the glue used may not be compatible with the foam and could be doing more harm than good.

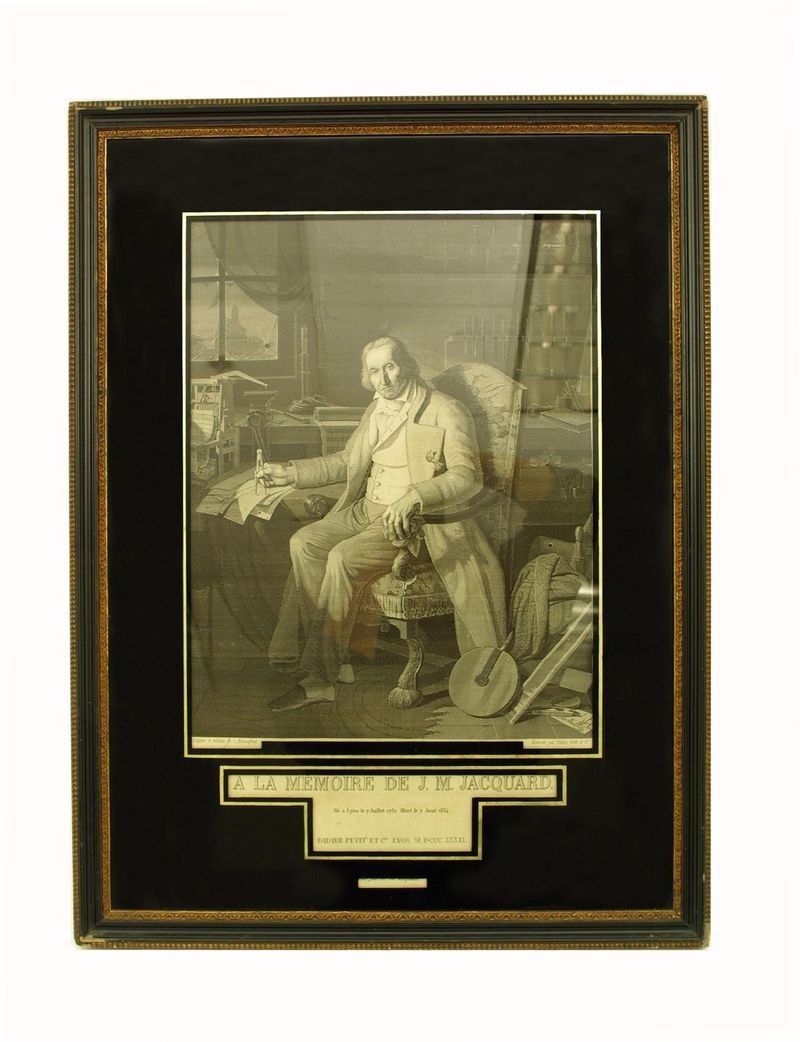

Portrait of Joseph-Marie Jacquard, ca. 1840, Loan of Gwen and Gordon Bell

The inherent harm, or vice, of an artifact’s construction is a common reason to consider conservation. The visual inspections of the NCR 304 model and the Honeywell fox led us to reflect on another item: the portrait of J.M. Jacquard. A silk weaving created in 1839, the portrait was showing some stains most likely due to acids migrating from the backing board into the silk. Acid migration is a leading cause of slow decay and irreversible damage if left untreated. Considered one of the most famous images of early computing, there are only ten samples of this same weaving including those in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Science Museum, and the Art Institute of Chicago. CHM clearly has a responsibility to provide outstanding care for such a rare piece of history.

The problem is none of these artifacts has health insurance. By insurance I mean that despite ongoing needs, very few non-art museums have the budget to keep a conservator on staff who could provide regular check-ups and health care for the collections. Some might say that because CHM’s collection is so young, it shouldn’t have the same needs an old collection—like Renaissance paintings—might have. But that is not true. The majority of physical objects in CHM’s collections are a mish-mash of plastics and metals, some of which actively corrode each other. The most obvious detriment to the collection is the prevalent attitude by manufacturers and consumers alike that computers were made be used, used up and disposed. While in service, none of the artifacts in our collection were perceived as historic and some have seen hard times. The long-term aging of the manufacturing processes hasn’t been observed over time by conservators. Thus, staff must rely on the results of conservation tests performed on other, similar materials to determine the best course of remediation.

While it’s most often not necessary to head for the emergency room, we do need to consult the specialists. Most of the conservators I’ve met are artists with chemistry backgrounds (or vice versa) who hold multiple advanced degrees. Like curators and registrars, conservators are bound to an ethical oath to ‘first do no harm’ to artifacts. They are physicians of a sort, spending considerable time assessing and researching the composition and life history of individual artifacts. Depending on how an object is constructed or damaged, conservators may consult with peers to develop an appropriate treatment proposal. Treatment can take weeks depending on the root cause of the problem and repair requirements. And anyone who’s been hospitalized knows how expensive that can get.

CHM has consulted with two local conservators, who specialize in objects and textiles. Tracy Power, object conservator, has treated large-scale bronze sculptures, pottery and ceramics in top collections, such as the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Textile conservator, Hannah Riley, once cared for the gowns worn by Queen Elizabeth II and Princess Diana and for the Dalai Lama’s prayer banners. I was thrilled to learn she was already familiar with Jacquard’s weaving techniques. We are extremely fortunate to have these two highly respected conservators here in the Bay Area.

The repairs to the NCR 304 model are straightforward: re-bonding the loosened parts with archival adhesive. But the fox and weaving require surgery. To give the Honeywell fox steady legs on which to stand again, Tracy Power will remove the old adhesive and apply a suitable one, strengthen the legs by inserting support rods and reapply loose components. CHM will also purchase a custom mount so the fox can be safely displayed. To stabilize Jacquard’s portrait, Hannah Riley will separate it from its highly acidic support board, mat and frame, then wash the fabric in a neutralizing solution. She will collaborate with an archival framer to select new glass in the style of the original reverse-painted glass, then re-frame it using archival materials and techniques. Like human patients, the treatments will be documented and stored in the object’s permanent files at CHM.

And as for the insurance? This is where you come in, gentle reader. Assessing the fox, the model and the portrait aren’t just opportunities for Collections staff—they’re also the means for Museum’s supporters to personally and directly preserve computing history. CHM has recently launched the Adopt An Artifact program to provide our many supporters with the chance to select a featured object and fund its conservation, in full or in part. Donors will be recognized on the webpage and in display labels, receive images of “their” adoptee, and receive invitations to behind-the-scenes tours and private viewings. Those who participate at the full sponsorship level will be featured in an online story and receive permanent recognition.* Did I mention that adoptions make excellent gifts to honor friends and family? Consider the venture capitalist in your life who has everything.

Stay tuned. I plan to blog more on these artifacts as the funding grows and they undergo treatment. I hope you’ll partner with us to ensure the Honeywell fox, J.M. Jacquard’s portrait and the NCR 304 sales model each live a full, happy life.