No doubt, my dad’s interest in old stuff is one of the reasons I’m so passionate about museums. My dad was a tinkerer. Buying, restoring and selling antique clocks was only his hobby. But you’d never know it by the dozens of gingerbreads, O.G.’s, French mantle, cuckoos, long case and more clocks that chimed night and day all throughout the house…and the basement…and the garage…and relatives’ homes. He restored clocks back to working condition, sometimes with parts he’d picked up at auctions. But restoring objects for personal use is very different from preserving or conserving artifacts in a museum’s collection.

The IBM 1401 restoration project began in 2004 when CHM acquired two complete IBM 1401 systems from Germany and the United States. A team of 20 Museum volunteers of mostly retired IBM engineers restored the machines after 20,000 hours in 500 works sessions over 10 years.

In the course of my work managing CHM’s collections, I often hear people use the terms preservation, conservation, and restoration interchangeably. In everyday use, that’s fine. However, these terms actually mean something quite different inside the walls of a museum. Here’s the insider perspective, examples for understanding the differences, and even some ways that visitors can help.

Preservation—or more accurately preventive conservation—is the practice of maintaining artifacts by providing a stable storage or display environment in order to minimize further damage or deterioration. Deterioration may be caused by environmental factors or by inherent vice, the unstable nature of an artifact’s composition. For example, paper may include lignin, acid and formaldehyde used in the paper’s manufacture and all of which contribute to its inevitable breakdown. Museums can really only slow the process of deterioration. Preventive conservation is typically accomplished by controlling temperature, humidity, light, security, mishandling, and other potentially damaging agents.

At the Computer History Museum, we maintain secure facilities in which our collections are housed and exhibited, monitor environmental conditions, treat for pests, utilize archivally safe products for cleaning and storage, and thoroughly document our collections and how they are utilized. To prevent damage from naturally occurring oils in people’s hands, staff must wear gloves whenever handling objects. As long as artifacts are kept in a stable environment, very few objects—even very old ones—are actually going to self-destruct (except cellulose nitrate film which spontaneously ignites).

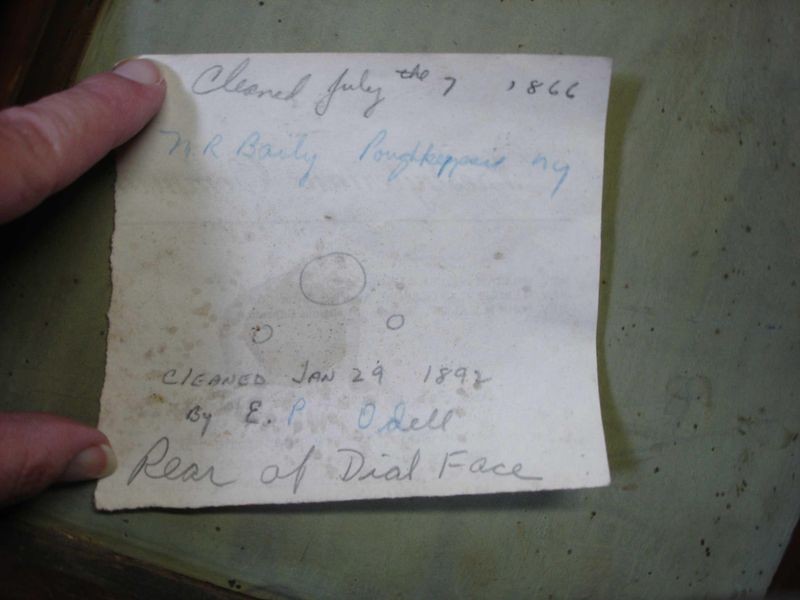

Let’s face it, no object is truly “built to last.” Instead, they are made to be used. Thus, historical artifacts are typically worn by normal use or were damaged in their previous environments. Sometimes objects are perceived as “damaged goods” if marked or altered. But the evidences of age are simply a part of an artifact’s past and those markings may illustrate patterns of use which actually increases its historic and cultural values. In museums we see this as part of the object’s history or provenance.

True that those artifacts differ from their original “like-new” appearance and can seem less aesthetically pleasing. But the “new in box” value impressed upon our commercial culture and wallets has little significance in a history museum. So why and when do museums conserve or restore objects? Most often when an artifact is to be displayed, used in research or demonstrated.

Interventive conservation is the practice of mitigating further deterioration. Conservation as performed by a professional conservator may mean specialized cleaning or the removal of agents that cause damage. The goal is to treat an artifact so that it can be gently handled, safely stored or displayed without further risk of damage. For example, a professional paper conservator may replace a badly damaged book binding in order to stabilize the book’s storage and handling. The original binding is preserved and the treatment process is fully documented and photographed.

Like physicians, conservators follow strict ethical standards including the rule of “first, do no harm.” They employ methods of reversible stabilization, meaning that any treatments they perform can be undone with no ill effect to the artifact. Because of their high level of expertise, professional conservators are in high demand and treatments are expensive. Conservation is not an attempt to return an object to its original state. Those efforts are more commonly known as restoration.

Best practices dictate that restorers document their work. This note transcribes the marks left by horologists of the past to uncover the extent of their labors on an antique clock.

Restorations play an important role in interpreting and retelling history because they provide a chance to share an often-intergenerational experience. Thanks to my dad this included learning to wind clocks, always resetting the hands in a clockwise motion, knowing which one always played Westminster chimes two minutes slow, and discovering why clocks once had wooden gears. But restorations in a museum are undertaken only after careful consideration of the ethics, likelihood of achieving success, proposed treatment plan and ultimate intended use of the artifact. If the object cannot serve to demonstrate a truly revolutionary principle or advance in technology, then it really cannot take up valuable space in the gallery.

Restoration equals permanent change. Cleaning and replacing significant parts, whether original to the object’s manufacturer or not, alter the historical integrity of an artifact. Once changed an object’s provenance has also been altered and it is no longer a true document of its place in history. That’s a big deal in museums, which are considered by the majority of Americans to be the most trustworthy source of information about the past.

If performed by persons who don’t understand how a system was designed or if they use archivally unsafe practices, cleaners or chemicals, a restoration may cause irreversible damage immediately or in the future. A cleaning agent used now may cause wooden gears to dry and crack in the future. The original maker’s work is no longer intact and its function and research value have diminished. In the end, such losses reduce the object’s cultural and material values or potentially its ability to function or be exhibited. Therefore, each step of the process must be carefully considered and always documented.

I’m sometimes asked, “When is the museum going to get everything up and running?” My answer is always, “How many football fields do you have to donate?” It’s not to be snarky, but with the hardware collection alone estimated at >35,000 items it’s really not feasible to undertake such a massive endeavor. And really, if CHM did do that it would take visitors months—possibly years—to experience everything being exhibited and operated. Who has that kind of time to visit one museum?

Right now, CHM’s strategy is dedicated to collecting and preserving at least one unaltered example of the major technological advances of the Information Age. If a second system in outstanding condition that can demonstrate significant principles in programming, design, and function makes its way to the Museum, the curators might consider it as a candidate for restoration and demonstration purposes. But we’d need to double up on some pretty massive systems to accomplish such a feat! Equally, few restoration projects occur simply because the museum has limited space within which to house a restoration shop and limited resources to demonstrate the restored object or system. It’s very much a quality over quantity decision. We want to provide the best visitor experience possible, so rather than set up moments of nostalgia we offer opportunities for real learning. Have you played Spacewar! on the PDP-1 yet?

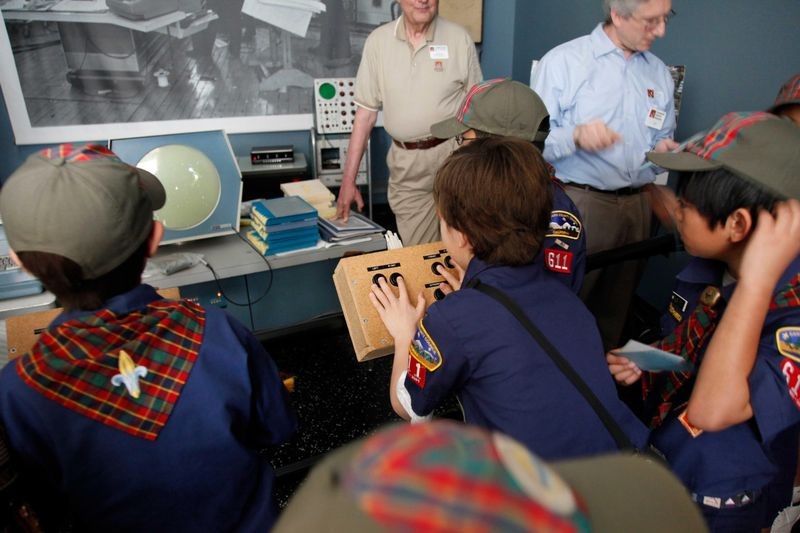

A Scout Tour hosted by the PDP-1 Restoration Team shows just how much fun a younger generation can have with an old computer.

My dad’s projects proceeded only after lots of research, communicating with fellow horologists, and I suppose by the space my mom was willing to lend to (yet another!) clock. The little notes he slipped inside each describe the clock’s history, the maker’s bio and any peculiar quirks of its workings. Of course, he always etched his mark and the date of repair on the back of the workings, taking responsibility for alterations. Of those he gifted to me, I’m grateful to keep his legacy going.

And that’s key to preserving history—inviting others to get invested and join you. Visitors can help CHM preserve artifacts by minding three simple guidelines while in the galleries: 1) don’t touch the artifacts to help keep them from being damaged; 2) keep all food and drink in the Cloud Café to avoid spills and pests; and 3) take all the photos you want but be sure to turn off the flash. Spread the word that, together, we’re doing the right things to promote computer history for generations to come.