The Adobe Corporation has announced that cofounder John Warnock died at the age of 82 on August 19, 2023. His death will be a loss to many, most of all his closely knit family, but extending as well to many professional colleagues and, indeed, to us at the Computer History Museum.

Among his many interests, Warnock was engaged with history. He collected books from across the history of science, technology, and mathematics. He donated artifacts and documents from the history of Adobe to CHM, where he became a fellow in 2002, participated in our workshop on the history of desktop publishing in 2017, and was instrumental in facilitating our recent public release of the PostScript source code. Indeed, we were working with Warnock to finalize our two-part oral history interview with him when we received the news of his passing. We could think of no better way to remember him, than to make this interview available today.

CHM’s Oral History with John Warnock, Part 1. Download transcript here.

CHM’s Oral History with John Warnock, Part 2. Download transcript here.

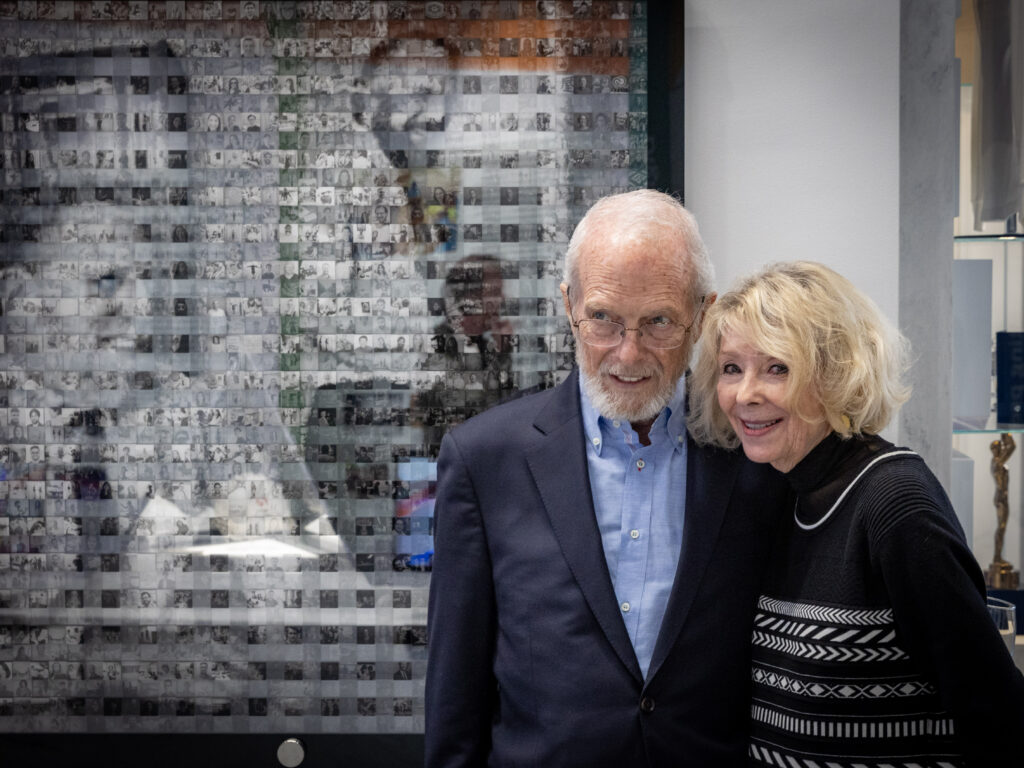

The Computer History Museum collaborated with Adobe to create the Adobe Experience Museum on the ground floor of the new Adobe Founders Tower in downtown San Jose. Shown here are John and Marva Warnock at the ribbon cutting in January 2023.

John Warnock was born in the suburbs of Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1940. His childhood home was thoroughly artistic, with parents and siblings alike drawing and painting. By his own description, Warnock was a “lackluster student,” but that by no means meant that he was without interests. Working as a “stock boy” in a photography shop during the summers, fueled—and financially supported—what turned out to be a life-long passion for photography.

A major shift in Warnock’s life, however, came through a dynamic high school mathematics teacher. Warnock said, “He had a very interesting way of approaching things. He said, 'We’re going to use a college trigonometry book. How many of you can solve all the problems in the book?’ A week later, a guy would come in with a stack of paper and have solved all the problems in the book. He sort of challenged people, and a big part of the class would do it. I mean, just do it. He was an amazing guy and I fell in love with mathematics . . . it changed me from being a non-student to a good student.”

Graduating from high school in 1958, Warnock followed family tradition and attended the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. While he was set on studying mathematics, little else was decided: “I thought I’d probably end up being a teacher at that time. I really hadn’t thought about it much. I guess I’d thought about being a photographer or something like that, but I would say teaching or photography or something like—I really didn’t think about it much.”

Finishing his undergraduate studies in just three years, Warnock stayed on at Utah for a master's in mathematics. From there, he got a job at IBM in 1963 where he had his first exposure to computers: “Well, with mathematics behind you and learning FORTRAN and things like that, it was fairly straightforward. I learned how to do that. But mostly when you . . . started visiting customers and solving real problems, that’s when you started to learn about operating systems, how [they] worked. As my customers would always say, ‘You’re here so we can train you’ . . . So I learned how to program.” One of the accounts he had at IBM was the University of Utah Computer Center.

The prospect of being drafted for the Vietnam War led Warnock back to the University and a deferment so that he could pursue a PhD in mathematics. To support himself, he worked in the University’s Computer Center, continuing much of the work he had done as an IBM employee. There, he encountered Gordon Romney, the first graduate student in the newly formed Computer Science Department then being formed by Dave Evans, who had come to Utah with a huge ARPA contract to make it a center of computer graphics research: “They were experimenting with displays and how you do three-dimensional stuff on displays. One day Gordon Romney, who was working on it, came in and he said, “I have a problem,” and he sort of described the hidden surface problem to me. I was in the Computer Center. I thought about that problem and then said, “Gee, here’s a way you could solve it.” Gordon said, “You probably ought to talk to Dave.”

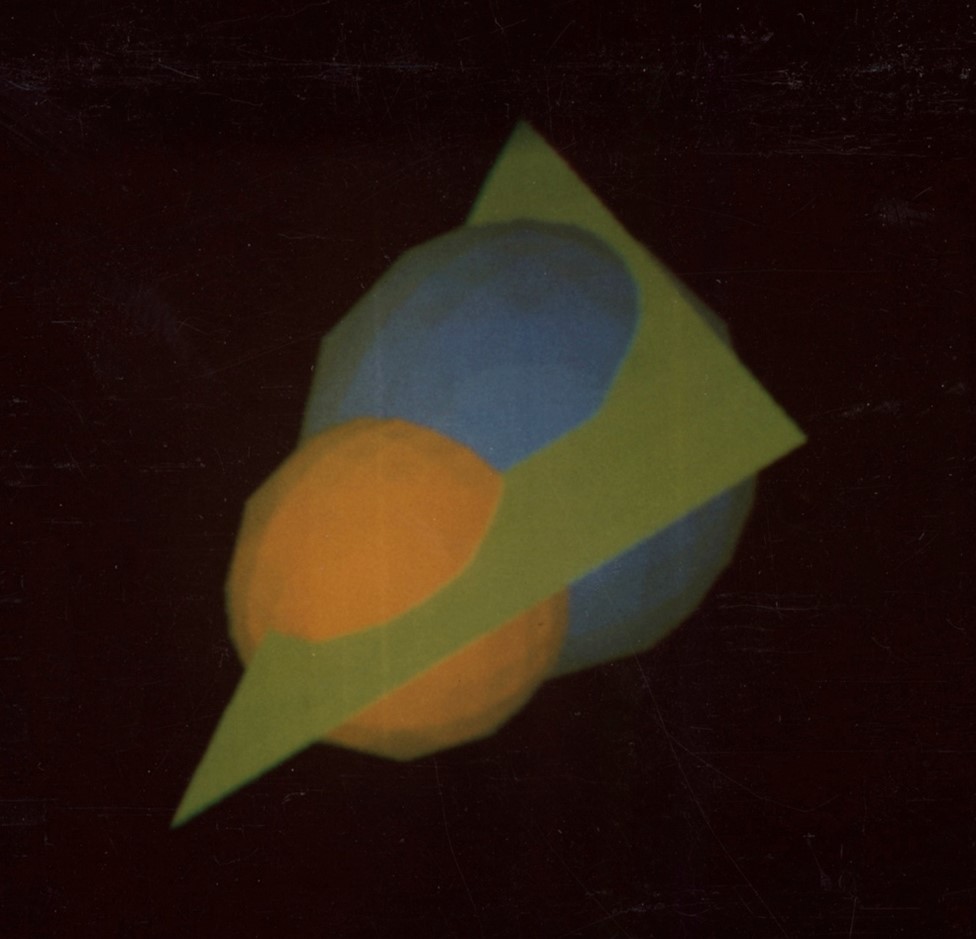

John Warnock’s journey into computer graphics at the University of Utah.

Warnock did, and soon switched to pursuing a PhD in computer graphics under Dave Evans. With Evans’ recruitment of Ivan Sutherland to the Utah faculty, it did indeed become the most important site of computer graphics research, and Warnock was in the thick of it. The department also connected Warnock to the larger community of ARPA-supported computer science researchers across the country, which had a profound impact on him and on computing: “It was great. No, it was really great. I think that’s essentially sort of what launched all computing that we know today.” Warnock made significant strides in creating 3D color images as part of his graduate studies at the close of the decade, and then found immediate work in computer services for a few years.

An early color 3D graphics image by John Warnock from the late 1960s. Courtesy John Warnock.

In the early 1970s, Dave Evans recruited Warnock back into the computer graphics fold, hiring him into the firm Evans and Sutherland. Dave Evans and Ivan Sutherland had started the firm in Utah to pursue the commercial potentials of 3D computer graphics and animations. Soon, Warnock was opening a new Evans and Sutherland office in Mountain View, California, to work on an ambitious 3D color graphics powered simulation of the New York harbor for training ship pilots.

With his success with the Harbor Pilot Simulator, and a reorganization of Evans and Sutherland in the works, Warnock was asked to move back to Utah to become a vice president at the company. Interested in remaining in the Bay Area, he reached out to a friend, William Newman, from Utah computer graphics who was now working at the nearly Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC). Newman quickly connected him to Chuck Geschke, another member of the ARPA community of computer scientists who was also working at PARC. The pair met, and as Warnock recalled: “We’re roughly the same age, and roughly the same education. We have the same number of kids that are the same ages. We both refereed soccer. We hit it off well. He said, ‘I’m starting a new laboratory called the Imaging Sciences Laboratory. I’d like to have you interview.’”

Warnock quickly joined Geschke’s lab: “My primary responsibility was to make device-independent graphics, so that a piece of software could drive not only the bitmap display, it could drive color displays or grayscale displays, and deal with a much broader spectrum of stuff. But, also, potentially could drive high resolution printers.” This work directly fed into a new challenge for the group. PARC’s researchers had created a radical new kind of networked personal computer, the Alto, that Xerox was now turning into a real product. As Warnock recalled: “[Xerox] has started to make the Star a commercial product . . . They found that they had no universal printer protocol, and so they said, “Well, we’ve got to sell printers to these guys. Why don’t we have PARC design a printer protocol for Xerox?” This was also one of the most fascinating projects in the world, because we very rarely met. We did the whole design via email, and we’d have arguments via email, and everything.”

Warnock put much of what he had learned about computer graphics at Evans and Sutherland and PARC into this new effort, and the printing protocol that came out of it, called Interpress. While he and Geschke thought it had significant potential for Xerox and for the computing world at large, Xerox told them it would be over a half-decade before it could be fully implemented by the company. Warnock recalled: “I went into his office, and I said, ‘We can live in the world’s greatest sandbox for the rest of our life, or we can do something about it.’” They did, leaving PARC to create Adobe in 1982.

John Warnock on cofounding Adobe.

Chuck Geschke (seated) and John Warnock (standing) at Adobe. © Doug Menuez/Stanford University Library Systems

At Adobe, they would create this universal printing protocol—allowing diverse computers and programs to create high quality text and images on a great variety of printers—more fully along the lines Warnock thought best. Everything to be printed, including fonts, would be treated as geometry, as mathematically described shapes. Adobe’s protocol, PostScript, also used careful mathematics to ensure the quality of text on printers and screens. As Warnock recalled: “The first time we tried this, it just worked like a champ.”

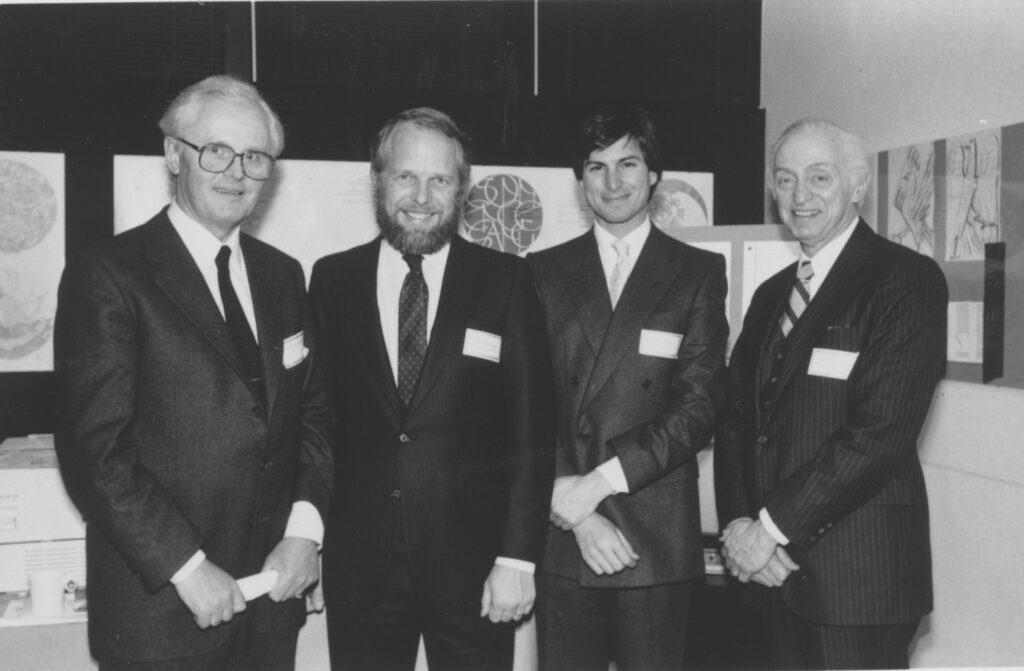

PostScript became a roaring success for Adobe, for both its mathematical approach and for a savvy insight by its founders. They licensed fonts from the biggest typography houses worldwide: “Chuck and I had a very strong feeling that it was worth your weight in gold if you could license the real thing. Now, you could have the same outlines, but if you couldn’t call it Times Roman, and you couldn’t call it Helvetica, the design community wouldn’t trust it.”

Alliances were essential for the success of Adobe’s digital press. This photograph from the January 1985 debut of Apple’s LaserWriter—that relied on Adobe’s Postscript—captures the alliances that Adobe forged and would prove critical to the growth of the company. Shown here, far left is then-President of the Linotype Group, Wolfgang Kummer, who licensed Linotype’s famous fonts; next to Kummer is John Warnock, Adobe cofounder and architect of Postscript, followed by Steve Jobs, cofounder and then chairman of Apple and finally Aaron Burns, cofounder of the International Typeface Corporation, which also licensed its large typeface library to Adobe. Courtesy John Warnock.

Following the success of PostScript, Warnock went on to become a champion for important new application products for Adobe. He was deeply involved with the creation of Illustrator, a popular drawing application closely tied to PostScript technology. He was a key champion for Photoshop, the pathbreaking application for digital photography: “I started my own dark room I guess when I was 15 years old and I started mixing my own chemicals for the dark room when I was like 16 or 17 and I had my own enlarger and I had a graphics camera and I was on the yearbook photography staff, so I’ve had a long history with cameras and photography. And I learned to do a lot of things in the dark room and I started seeing those in Photoshop, the things you could do in a dark room and then it became totally obvious that anything you could do with an image, you could do in software.”

John Warnock on how his experiences in photography prepared him for Photoshop.

Importantly, John Warnock was responsible for the creation of PDF. Early on in the company, he had figured out a way to modify PostScript so that printing would happen faster in Steve Jobs’ first demo of the LaserWriter, Apple’s first laser printer for the Macintosh. Years later, in 1991, he envisioned that this same kind of modification would be key to creating a new kind of electronic document that would have high visual quality but also be safe for electronic sharing through email or the internet. From the launch of this new format, PDF, in 1993 and for years afterward, Warnock championed the effort. After several years, PDF caught on like wildfire, and has become an international standard for digital documents and their exchange. In all of these application efforts, Warnock kept the user perspective at the forefront, because he was one himself: “And from day one, I’ve used Illustrator every day of my life. And I’ve used Photoshop every day of my life. And I’ve used Acrobat every day of my life.”

PostScript. Illustrator. Photoshop. Lightroom. PDF. InDesign. Behind all of these technological success stories, Warnock saw the importance of culture, of bringing people together in a way they could seize opportunity sustainably: “I think a big part of the company . . . is the culture of the company. And one of the things that Chuck’s always said is always hire people who are smarter than you. And we’ve also tried to be very egalitarian . . . it’s always been giving people opportunity, it’s always taking care of people, being fair . . . [W]hen Chuck and I first started the company, we explicitly said to each other, we want to build a company that we would like to work for. Okay, this is sort of number one. We also felt that transparency is really, really, really important . . .We sort of tried to bend over backwards to keep both the cultural and ethnic distribution of the company and the male-female balance there and I think we do really well at that . . . always believed that diversity, hybrid vigor is great!”

John Warnock on the values behind Adobe’s corporate culture.

While the deaths of John Warnock and Chuck Geschke are truly a great loss, their commitments to technological innovation, artistic excellence, diversity, and humane values are enduring examples of lives well-led and that should be studied by generations of technologists to come.