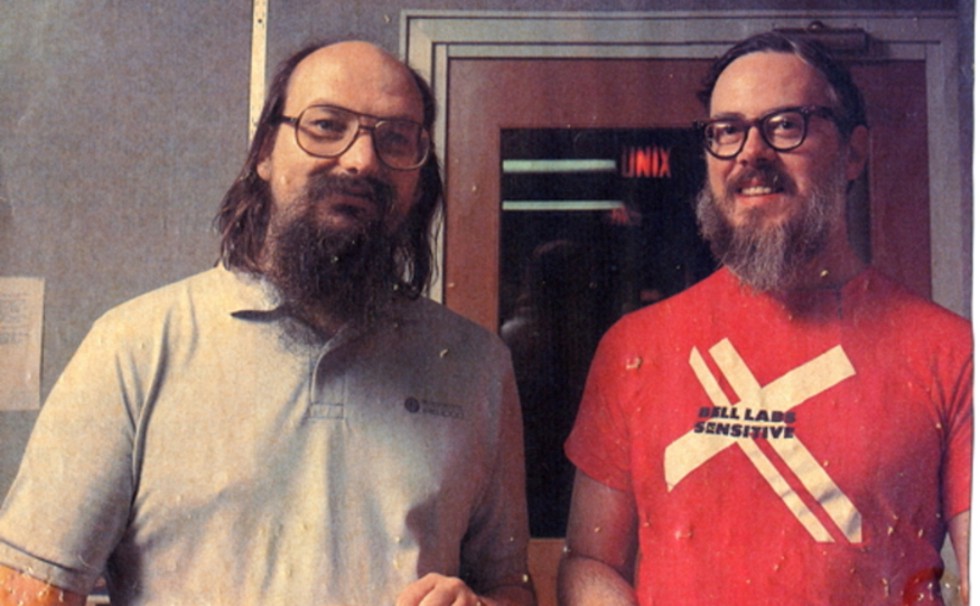

Many of you, dear readers, will have heard of Dennis Ritchie. In the late 1960s, he left graduate studies in applied mathematics at Harvard for a position at the Bell Telephone Laboratories, where he spent the entirety of his career. Not long after joining the Labs, Ritchie linked arms with Ken Thompson in efforts that would create a fundamental dyad of the digital world that followed: the operating system Unix and the programming language C. Thompson led the development of the system, while Ritchie was lead in the creation of C, in which Thompson rewrote Unix. In time, Unix became the basis for most of the operating systems on which our digital world is built, while C became—and remains—one of the most popular languages for creating the software that animates this world.

Unix creators Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie. Original source unknown.

On Ritchie’s personal web pages at the Labs (still maintained by Nokia, the current owner), he writes with characteristic dry deprecation of his educational journey into computing:

“I . . . received Bachelor’s and advanced degrees from Harvard University, where as an undergraduate I concentrated in Physics and as a graduate student in Applied Mathematics . . . The subject of my 1968 doctoral thesis was subrecursive hierarchies of functions. My undergraduate experience convinced me that I was not smart enough to be a physicist, and that computers were quite neat. My graduate school experience convinced me that I was not smart enough to be an expert in the theory of algorithms and also that I liked procedural languages better than functional ones.”1

Whatever the actual merits of these self-evaluations, his path certainly did lead him into a field and an environment in which he made extraordinary contributions.

It may come as some surprise to learn that until just this moment, despite Ritchie’s much-deserved computing fame, his dissertation—the intellectual and biographical fork-in-the-road separating an academic career in computer science from the one at Bell Labs leading to C and Unix—was lost. Lost? Yes, very much so in being both unpublished and absent from any public collection; not even an entry for it can be found in Harvard’s library catalog nor in dissertation databases.

After Dennis Ritchie’s death in 2011, his sister Lynn very caringly searched for an official copy and for any records from Harvard. There were none, but she did uncover a copy from the widow of Ritchie’s former advisor. Until very recently then, across a half-century perhaps fewer than a dozen people had ever had the opportunity to read Ritchie’s dissertation. Why?

In Ritchie’s description of his educational path, you will notice that he does not explicitly say that he earned a PhD based on his 1968 dissertation. This is because he did not. Why not? The reason seems to be his failure to take the necessary steps to officially deposit his completed dissertation in Harvard’s libraries. Professor Albert Meyer of MIT, who was in Dennis Ritchie’s graduate school cohort, recalls the story in a recent oral history interview with CHM:

“So the story as I heard it from Pat Fischer [Ritchie and Meyer’s Harvard advisor] . . . was that it was definitely true at the time that the Harvard rules were that you needed to submit a bound copy of your thesis to the Harvard— you needed the certificate from the library in order to get your PhD. And as Pat tells the story, Dennis had submitted his thesis. It had been approved by his thesis committee, he had a typed manuscript of the thesis that he was ready to submit when he heard the library wanted to have it bound and given to them. And the binding fee was something noticeable at the time . . . not an impossible, but a nontrivial sum. And as Pat said, Dennis’ attitude was, ‘If the Harvard library wants a bound copy for them to keep, they should pay for the book, because I’m not going to!’ And apparently, he didn’t give on that. And as a result, never got a PhD. So he was more than ‘everything but thesis.’ He was ‘everything but bound copy.’”2

While Lynn Ritchie’s inquiries confirmed that Dennis Ritchie never did submit the bound copy of his dissertation, and did not then leave Harvard with his PhD, his brother John feels that there was something else going on with Dennis Ritchie’s actions beyond a fit of pique about fees: He already had a coveted job as a researcher at Bell Labs, and “never really loved taking care of the details of living.” We will never really know the reason, and perhaps it was never entirely clear to Ritchie himself. But what we can know with certainty is that Dennis Ritchie’s dissertation was lost for a half-century, until now.

Dennis Ritchie (right) around the time he started working at Bell Laboratories, with two other figures from the Labs: His father Alistair Ritchie (left) and electronic switching pioneer William Keister (center). Courtesy Ritchie Family.

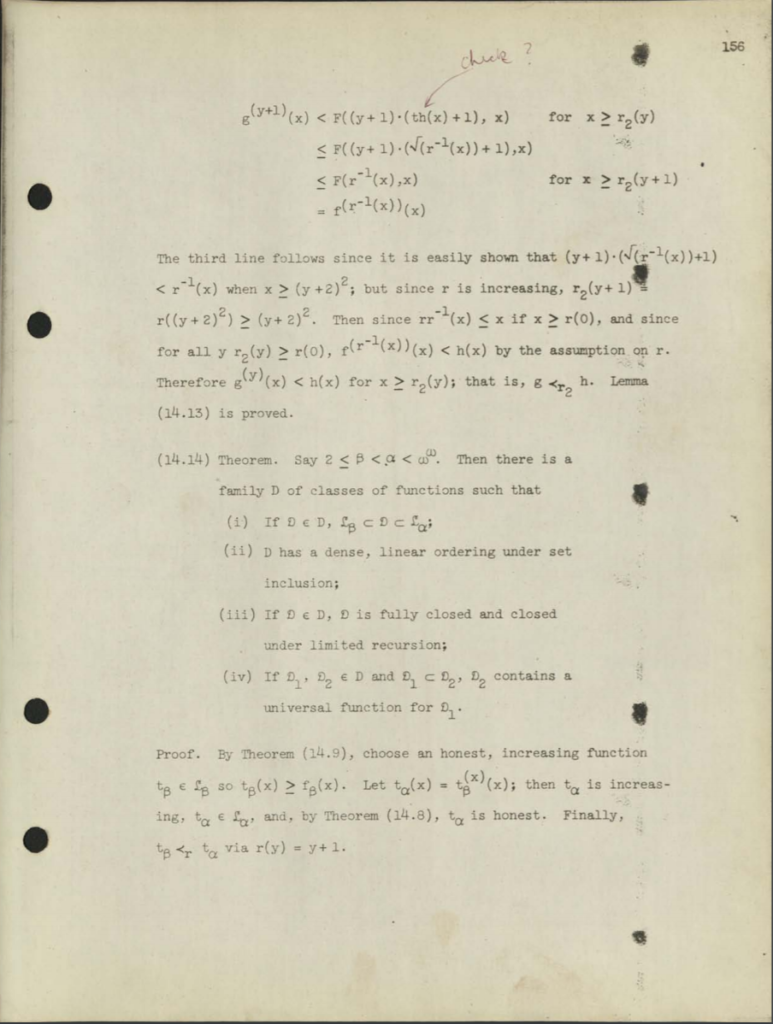

Within the Dennis Ritchie collection, recently donated by Ritchie’s siblings to CHM, lay several historical gems that we have identified to date. One is a collection of the earliest Unix source code dating from 1970–71. Another is a fading and stained photocopy of Ritchie’s doctoral dissertation, Program Structure and Computational Complexity. CHM is delighted to now make a digital copy of Ritchie’s own dissertation manuscript (as well as a more legible digital scan of a copy of the manuscript owned by Albert Meyer) available publicly for the first time.

Page from Dennis Ritchie’s previously lost dissertation manuscript available publicly for the first time.

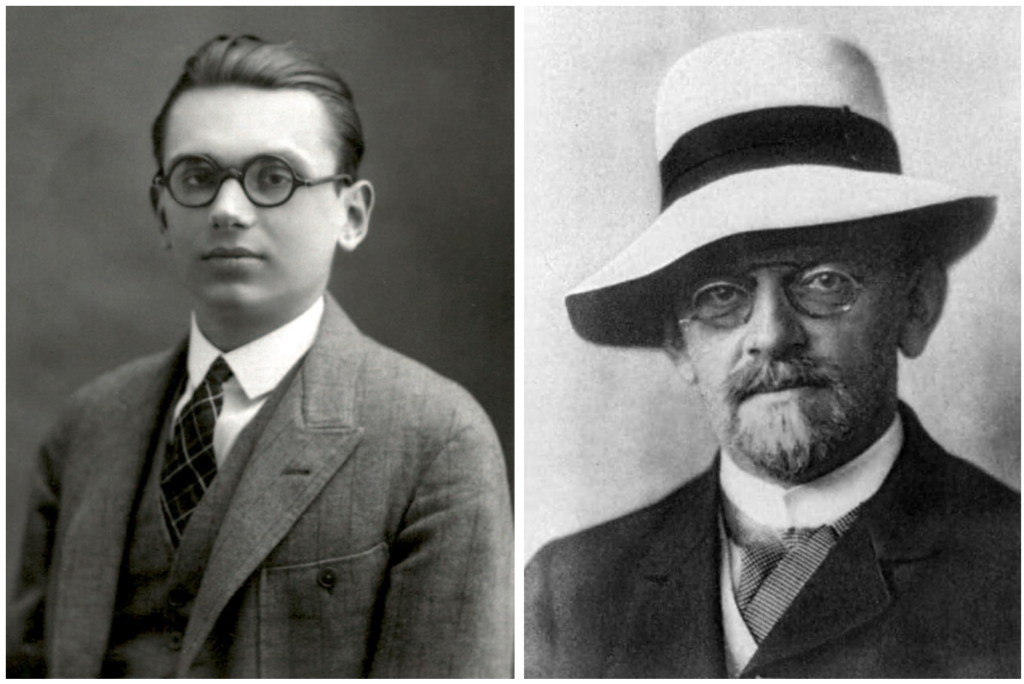

Recovering a copy of Ritchie’s lost dissertation and making it available is one thing, understanding it is another. To grasp what Ritchie’s dissertation is all about, we need to leap back to the early 20th century to a period of creative ferment in which mathematicians, philosophers, and logicians struggled over the ultimate foundations of mathematics. For centuries preceding this ferment, the particular qualities of mathematical knowledge—its exactitude and certitude—gave it a special, sometimes divine, status. While philosophical speculation about the source or foundation for these qualities stretches back to Pythagoras and Plato at least, in the early 20th century influential mathematicians and philosophers looked to formal logic—in which rules and procedures for reasoning are expressed in symbolic systems—as this foundation for mathematics.

Across the 1920s, the German mathematician David Hilbert was incredibly influential in this attempt to secure the basis of mathematics in formal logic. In particular, Hilbert believed that one could establish certain qualities of mathematics—for example, that mathematics was free of contradictions and that any mathematical assertion could be shown to be true or to be false—by certain kinds of proofs in formal logic. In particular, the kinds of proofs that Hilbert advocated, called “finitist,” relied on applying simple, explicit, almost mechanical rules to the manipulation of the expressive symbols of formal logic. These would be proofs based on rigid creation of strings of symbols, line by line, from one another.

In the 1930s, it was in the pursuit of such rules for logical manipulation of symbols that mathematicians and philosophers made a connection to computation, and the step-by-step rigid processes by which human “computers” and mechanical calculators performed mathematical operations. Kurt Gödel provided a proof of just the sort that Hilbert advocated, but distressingly showed the opposite of what Hilbert and others had hoped. Rather than showing that logic ensured that everything that was true in mathematics could be proven, Gödel’s logic revealed mathematics to be the opposite, to be incomplete. For this stunning result, Gödel’s proof rested on arguments about certain kinds of mathematical objects called primitive recursive functions. What’s important about recursive functions for Gödel is that they were eminently computable, that is they relied on “finite procedures,” just the kind of simple, almost mechanical, rules for which Hilbert had called.

Left: Kurt Gödel as a student in 1925. Wikipedia/Public domain. Right: David Hilbert, 1912. Wikipedia

Quickly following Gödel, in the US, Alonzo Church used similar arguments about computability to formulate a logical proof that showed also that mathematics was not always decidable, that is, that there were some statements about mathematics for which it is not possible to determine if they are true or are false. Church’s proof is based on a notion of “effectively calculable functions,” grounded in Gödel’s recursive functions. At almost the same time, and independently in the UK, Alan Turing constructed a proof of the very same result, but based on a notion of “computability” defined by the operation of an abstract “computing machine.” This abstract Turing machine, capable of any computation or calculation, would later become an absolutely critical basis for theoretical computer science.

In the decades that followed, and before the emergence of computer science as a recognized discipline, mathematicians, philosophers, and others began to explore the nature of computation in its own right, increasingly divorced from connections to the foundation of mathematics. As Albert Meyer explains in his interview:

“In the 1930s and 1940s, the notion of what was and wasn’t computable was very extensively worked on, was understood. There were logical limits due to Gödel and Turing about what could be computed and what couldn’t be computed. But the new idea [in the early 1960s] was ‘Let’s try to understand what you can do with computation, that was when the idea of computational complexity came into being . . . there were . . . all sorts of things you could do with computation, but not all of it was easy . . . How well could it be computed?”

With the rise of electronic digital computing, then, for many of these researchers the question was less what logical arguments about computability could teach about the nature of mathematics, but what could these logical arguments reveal about the limits of computability itself. As those limits came to be well understood, the interests of these researchers shifted to the nature of computability within these limits. What could be proven about the realm of possible computations?

Professor Albert Meyer of MIT, who was in Dennis Ritchie’s graduate school cohort, and shares his recollections of Ritchie in a 2018 oral history interview.

One of few places where these new investigations were taking place in the mid 1960s, when Dennis Ritchie and Albert Meyer both entered their graduate studies at Harvard, was in certain corners of departments of applied mathematics. These departments were also, frequently, where the practice of electronic digital computing took root early on academic campuses. As Meyer recalls:

“Applied Mathematics was a huge subject in which this kind of theory of computation was a tiny, new part.”

For both Ritchie and Meyer, theirs was a gravitation into Harvard’s applied mathematics department from their undergraduate studies in mathematics at the university, although Meyer does not recall having known Ritchie as an undergraduate. In their graduate studies, both became increasingly interested in the theory of computation, and thus alighted on Patrick Fischer as their advisor. Fischer at the time was a freshly minted PhD who was only at Harvard for the critical first years of Ritchie and Meyer’s studies, before alighting to Cornell in 1965. (Later, in 1982, Fischer was one of the Unabomber’s targets.) As Meyer recalls:

“Patrick was very much interested in this notion of understanding the nature of computation, what made things hard, what made things easy, and they were approached in various ways . . . What kinds of things could different kinds of programs do?”

After their first year of graduate study, unbeknownst to at least Meyer, Fischer independently hired both Ritchie and Meyer as summer research assistants. Meyer’s assignment? Work on a particular “open problem” in the theory of computation that Fischer had identified, and report back at the end of the summer. Fischer, for his part, would be away. Meyer spent a miserable summer working alone on the problem, reporting to Fischer at the end that he had only accomplished minor results. Soon after, walking to Fischer’s graduate seminar, Meyer was shocked as he realized a solution to the summer problem. Excitedly reporting his breakthrough to Fisher, Meyer was “surprised and a little disappointed to hear that Pat said that Dennis had also solved the problem.” Fischer had set Ritchie and Meyer the very same problem that summer but had not told them!

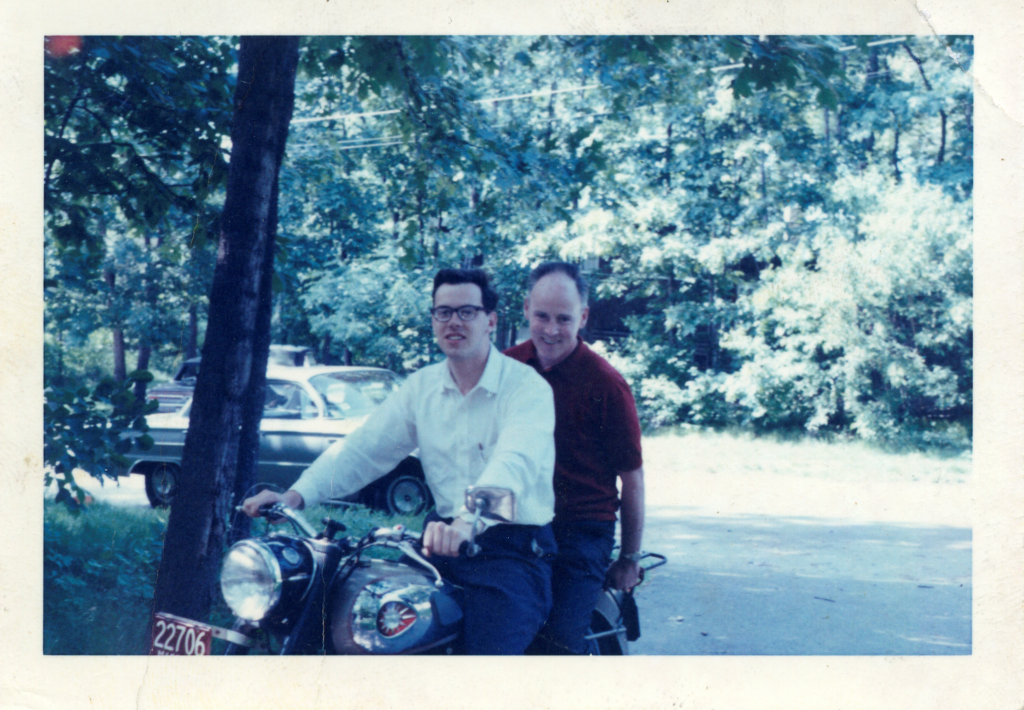

Dennis Ritchie, during his graduate school days. His father, Alistair E. Ritchie (who also worked at Bell Labs), is seated on the back of Dennis Ritchie’s BSA 650 motorcycle. Courtesy Ritchie Family.

Fischer’s summer problem was a take on the large question of computational complexity, about the relative ease or time it takes to compute one kind of thing versus another. Recall that Gödel had used primitive recursive functions to exemplify computability by finite procedures, key to his famous work. In the 1950s, the Polish mathematician Andrzej Grzegorczyk defined a hierarchy of these same recursive functions based on how fast or slow the functions grow. Fischer’s summer question, then, was for Meyer and Ritchie to explore how this hierarchy of functions related to computational complexity.

To his great credit, Meyer’s disappointment at summer’s end gave way to a great appreciation for Ritchie’s solution to Fischer’s problem: loop programs. Meyer recalls “. . . this concept of loop programs, which was Dennis’s invention . . . was so beautiful and so important and such a terrific expository mechanism as well as an intellectual one to clarify what the subject was about, that I didn’t care whether he solved the problem.”

Ritchie’s loop program solution to Fischer’s summer problem was the core of his 1968 dissertation. They are essentially very small, limited computer programs that would be familiar to anyone who ever used the FOR command for programming loops in BASIC. In loop programs, one can set a variable to zero, add 1 to a variable, or move the value of one variable to another. That’s it. The only control available in loop programs is . . . a simple loop, in which an instruction sequence is repeated a certain number of times. Importantly, loops can be “nested,” that is, loops within loops.

What Ritchie shows in his dissertation is that these loop functions are exactly what is needed to produce Gödel’s primitive recursive functions, and only these functions; just those functions of Grzegorczyk hierarchy. Gödel held out his recursive functions as eminently computable, and Ritchie showed that loop programs were just the right tools for that job. Ritchie’s dissertation shows that the degree of “nestedness” of loop programs—the depth of loops within loops—is a measure of computational complexity for them, as well as a gauge for how much time is required for their computation. Further, he shows that assessing loop programs by their depth of loops is exactly equivalent to Grzegorczyk’s hierarchy. The rate of growth of primitive recursive functions is indeed related to their computational complexity, in fact, they are identical.

As Meyer recalls:

“Loop programs made into a very simple model that any computer scientist could understand instantly, something that the traditional formulation…in terms for primitive recursive hierarchies…with very elaborate logician’s notation for complicated syntax and so on that would make anybody’s eyes glaze over—Suddenly you had a three-line, four-line computer science description of loop programs.”

While, as we have seen, Ritchie’s development of this loop program approach to computer science never made it out into the world through his dissertation, it did nevertheless make it into the literature in a joint publication with Albert Meyer in 1967.

Meyer explains:

“[Dennis] was a very sweet, easy going, unpretentious guy. Clearly very smart, but also kind of taciturn . . . So we talked a little, and we talked a about this paper that we wrote together, which I wrote, I believe. I don’t think he wrote it at all, but he read it . . . he read and made comments . . . and he explained loop programs to me.”

The paper, “The Complexity of Loop Programs,” was published by the ACM in 1967, and was an important step in the launch of a highly productive and regarded career in theoretical computer science by Meyer.3 But it was a point of departure for and with Ritchie. As Meyer recalls:

“It was a disappointment. I would have loved to collaborate with him, because he seemed like a smart, nice guy who’d be fun to work with, but yeah, you know, he was already doing other things. He was staying up all night playing Spacewar!”

At the start of this essay, we noted that in his biographical statement on his website, Ritchie quipped, “My graduate school experience convinced me that I was not smart enough to be an expert in the theory of algorithms and also that I liked procedural languages better than functional ones.” While his predilection for procedural languages is without question, our exploration of his lost dissertation puts the lie to his self-assessment that he was not smart enough for theoretical computer science. More likely, Ritchie’s graduate school experience was one in which the lure of the theoretical gave way to the enchantments of implementation, of building new systems and new languages as a way to explore the bounds, nature, and possibilities of computing.

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly noted that Patrick Fisher left Harvard for Columbia rather than Cornell.

Read Dennis Ritchie’s lost dissertation: