Throughout his long career, Dick Kramlich was celebrated as a trailblazer of venture investing in Silicon Valley, the United States, and beyond. Many of the firms he backed became billion-dollar concerns, and he enjoyed an untarnished reputation as direct and trustworthy, a “gentleman.”

This acclaim is richly deserved, but it is not the whole story. Fundamentally, Dick Kramlich thought of himself as an entrepreneur, and he viewed his successful career within that frame. In his oral history interviews with me for CHM, he made this crystal clear: “I regard myself as, first and foremost, an entrepreneur.” I believe this is the key to understanding his professional achievements.

In interviews with the Museum, Kramlich explained that he came from a family of entrepreneurs. His grandfather had cofounded the Safeway grocery chain, and his father had started a line of groceries that were acquired by Kroger in the mid-1950s. As a teen, Kramlich began to follow their example, using his savings to buy “half a train car of light bulbs” directly from a manufacturer, and reselling them for a profit. He found the experience thrilling, “…once you get it in your DNA, everything else is boring.”

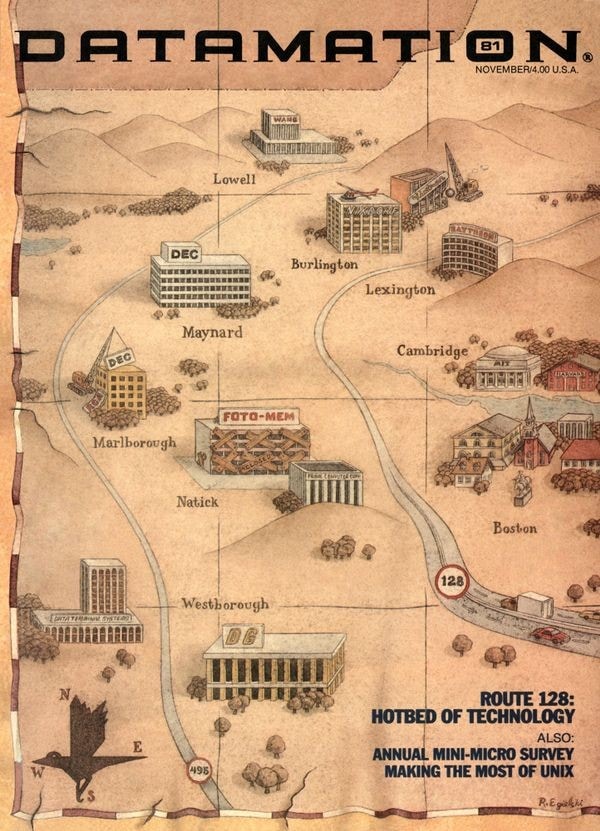

The young bulb magnate eventually made his way to Harvard Business School, following an undergraduate degree in history. By the mid 1960s, several of Kramlich’s friends had gone to work with the leading venture investment firms of the day, like Venrock and American Research and Development. He thought their work sounded exciting: identifying promising entrepreneurs, investing in them, and helping them succeed. Kramlich joined an established investment firm in Boston and was soon scouring for new opportunities up and down the Route 128 corridor, then in its full technological bloom. He found the excitement he was searching for in the entrepreneurial growth around new technologies.

Massachusetts’ legendary Route 128 corridor. 1981-11. From https://www.computerhistory.org/revolution/minicomputers/11/335/1899. © Technical Publishing Co.

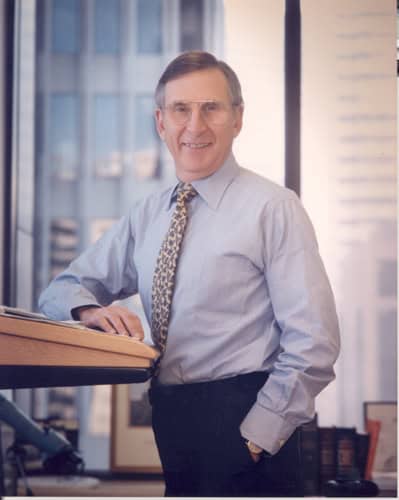

In 1968, an even more thrilling prospect dawned in Kramlich’s imagination. He read an interview with Arthur Rock who was gaining fame for his venture investments on the San Francisco Peninsula, an essential ingredient for why the region would soon become known as “Silicon Valley, USA.” Rock had been crucial to the formation of many of the key companies manufacturing the silicon integrated circuits that were transforming the world of computing, and electronics more broadly.

Rock’s venture partnership with Tommy Davis was ending, and in the article in Kramlich’s hands, Rock announced he was going to “…find a younger partner and do it all over again.” Struck by the possibilities, Kramlich dashed off a handwritten letter to Rock, with the intention of becoming that younger partner. Impressed, Rock began meeting with Kramlich, and in 1969, Kramlich moved to San Francisco and into his new venture partnership with Rock. The pair quickly raised $10 million from successful technologist-entrepreneurs, including several of the cofounders of Fairchild Semiconductor and Intel.

Arthur Rock, 1997, © Louis Fabian Bachrach

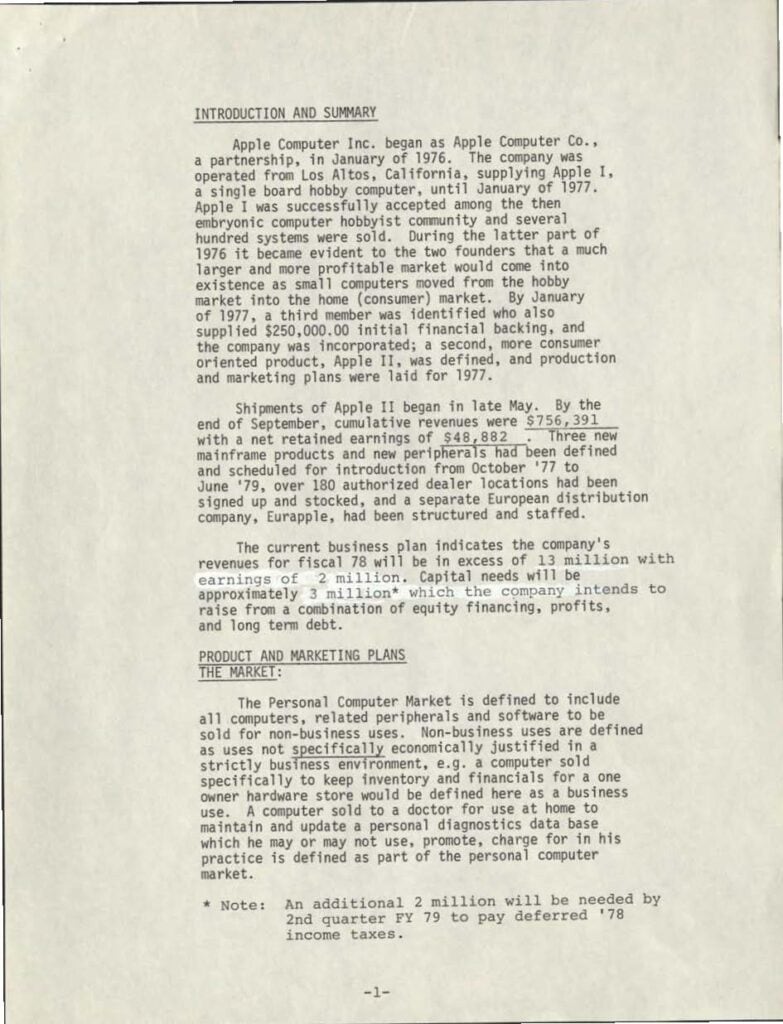

In 1977, as the partnership between Rock and Kramlich wound down, Kramlich was immersed in the rising personal computer industry, attending tradeshows and other gatherings and taking meetings with entrepreneurs. Early on, he set his sights on Apple. It, and its founders, had what he often called “religion,” a genuine and abiding passion for what they were doing, a true sense of mission: “I mean, there were two companies—one out of Berkeley and one out of Palo Alto at Stanford—they were better companies… technically in my judgement, but they didn’t have that something… the entrepreneurial spark, whereas Apple had it.” Through an old friend, Kramlich and Rock were able to make personal investments in Apple’s first round of outside financing.

A page from Apple’s “Preliminary Confidential Offering.” 1978–1982. Mike Markkula collection of early Apple Computer material. CHM catalog number 102783503. Gift of Mike Markkula.

At the same time, Kramlich was restless, exploring options for his next move. Where could he maximize his entrepreneurial excitement? He had serious conversations about joining Kleiner Perkins, a venture firm founded by successful technologist-entrepreneurs looking to support the next generations thereof in Silicon Valley. He was also weighing an open invitation to pursue venture investing at the investment bank Hambrecht and Quist in San Francisco. These were firms with the finest of reputations, and that meant they were well established.

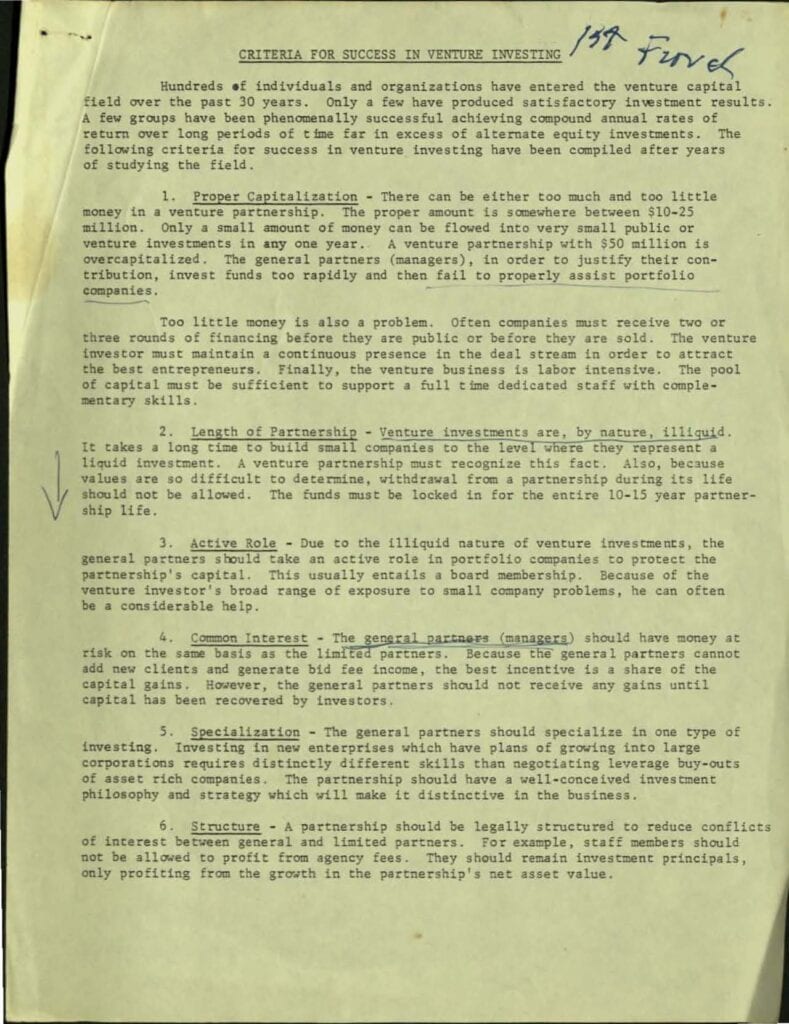

Through connections in the investing world, Kramlich began talking to Chuck Newhall and Frank Bonsal, two ambitious investors who wanted to establish a venture partnership of their own. They were entrepreneurial, intending to operate nationally (and eventually internationally) rather than regionally, and to support firms at different stages of development. They were also interested in building a partnership for the long term. Newhall and Bonsal would operate from the East Coast, and they wanted Kramlich to capture the opportunities in Silicon Valley. Kramlich responded to the lure of creating something new, and to the experience, ambition, and character of Newhall and Bonsal. They shook hands, and New Enterprise Associates (NEA) was launched.

Cofounders of NEA, from left to right: Chuck Newhall, Dick Kramlich, Frank Bonsal. June 1978. Chuck Newhall Papers. CHM catalog number 102644082. Gift of Charles W. Newhall.

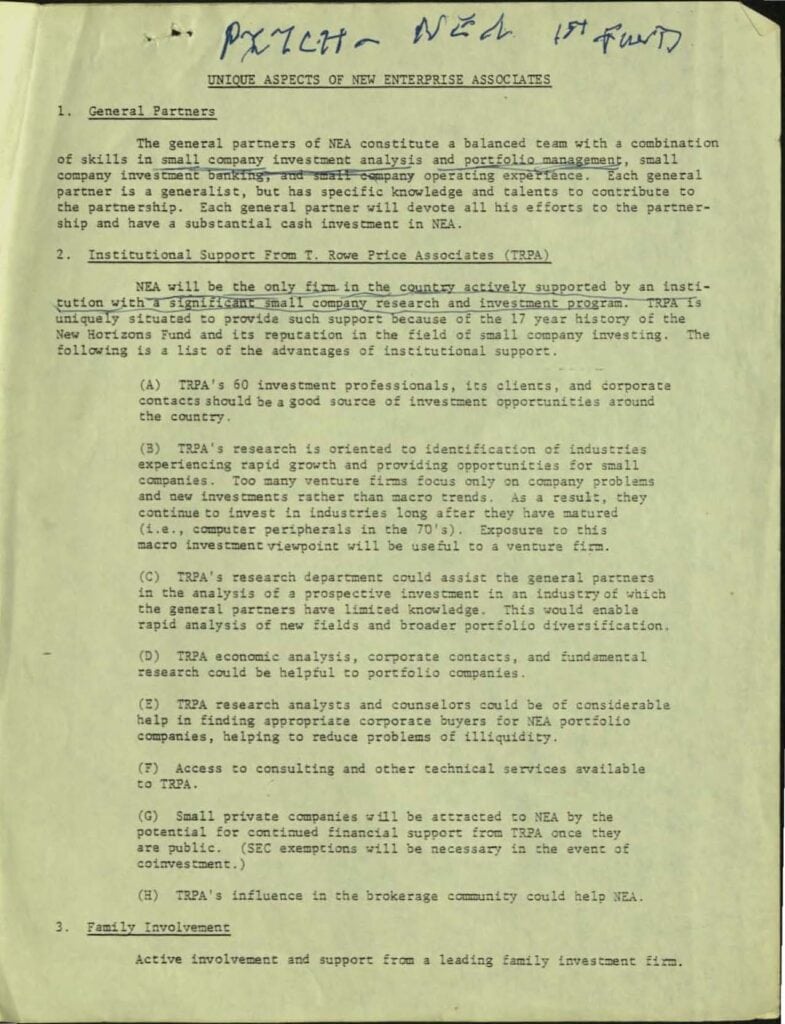

A document from the early days of NEA, detailing their overall approach for potential investors. ca. 1978. Chuck Newhall Papers. CHM catalog number 102644082. Gift of Charles W. Newhall.

One of the early pitch documents used by NEA’s cofounders for raising their first fund. ca. 1978. Chuck Newhall Papers. CHM catalog number 102644082. Gift of Charles W. Newhall.

In the following decades, NEA continually grew, raising larger and larger funds, and delivering high returns for its investors. Kramlich was equally if not more excited to have helped entrepreneurs create successful and meaningful firms, delivering on their “religion.” Some of the most recognizable firms with which he was involved include 3Com, Silicon Graphics, Immunex, Macromedia, and Juniper. But there is another much less well-known firm that illustrates so well what Kramlich meant when he said, “My philosophy is ‘I’m for the entrepreneur.’” It was named Forethought.

Dick Kramlich on the success of NEA, speaking in 2019 at CHM.

Forethought was a startup in personal computing software, created by two entrepreneurs who left Apple in 1982. Their ambition was to bring the power of the graphical user interface as developed at the fabled Xerox Palo Alto Research Center to the world of the IBM PC and its clones. Think Windows before Windows, but much more. Forethought’s software, called Foundation, was to be "an everything app," an operating system with every application folded intrinsically into it. Relational databases, documents, drawings, spreadsheets, Foundation would do it all. In 1983, NEA, led by Kramlich, made a first investment in the company.

Like the majority of venture capital backed startups, Forethought soon ran into serious problems. Foundation was not going to work. It was too ambitious for the state of the underlying hardware technology, and Oracle was not going to deliver a promised database system that would have been a key part of Foundation. Kramlich helped guide the firm into a pivot, recruiting Bob Metcalfe – the technologist-entrepreneur and Ethernet inventor behind 3Com—to Forethought’s board. To bring in much needed revenue, Forethought began distributing and marketing a small database program for the Macintosh, developed by a small firm in Massachusetts, called Filemaker.

The firm hired a new developer, Robert Gaskins, who assembled a small team to make a new product: Presenter. Gaskins was impassioned about the possibility to use What You See Is What You Get (WYSIWYG) graphical software, graphical user interfaces, and laser printers to allow knowledge workers of all stripes to create their own overhead presentations, handouts, and slides. Presenter would put the power of graphical personal computing in the hands of these knowledge workers, allowing them to better and more efficiently create vital communication aids. But while Gaskins and his team were developing Presenter, the numbers for Forethought were not adding up. The firm needed another round of investment.

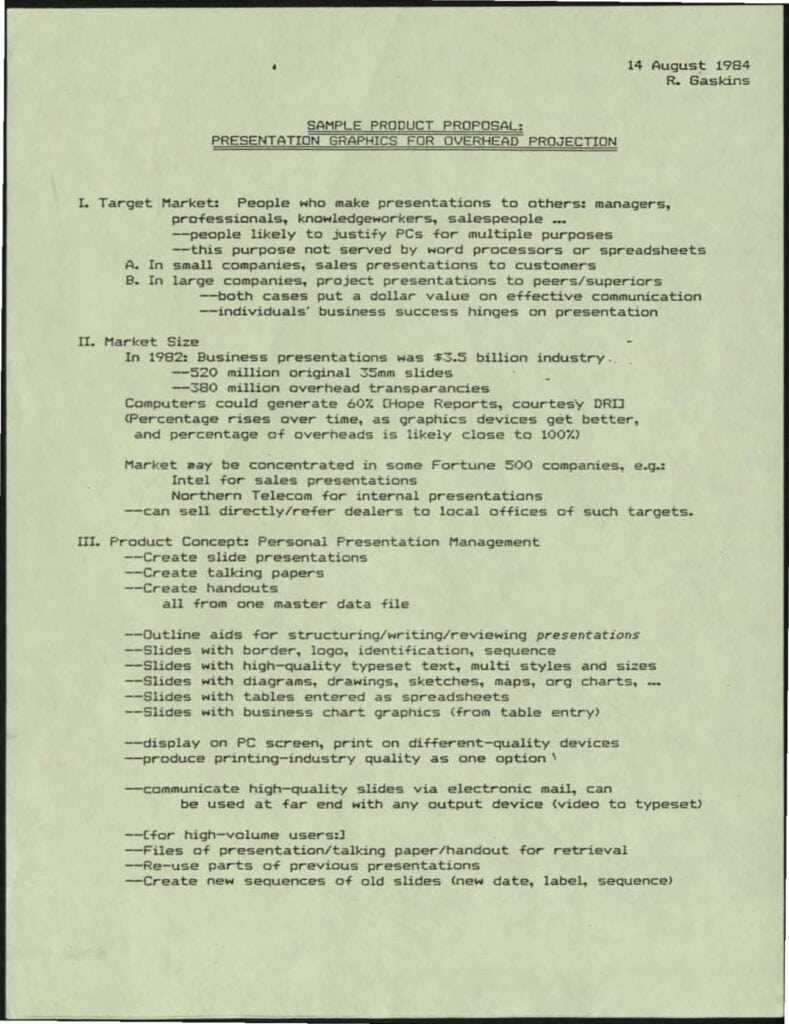

A page from a very early memo by Robert Gaskins about what would become PowerPoint. August 15, 1984. Dennis Austin PowerPoint Records. CHM catalog number 102733911. Gift of Dennis Austin.

NEA had already put two rounds of funding into Forethought, and now was being asked for a third. Despite Gaskins’, and now Kramlich’s, enthusiasm for the potential of Presenter, NEA decided against the third round. Even Metcalfe agreed, reminding Kramlich, “Dick, you know, there’s a time and a place to give up on these things.” Kramlich’s reply? “I don’t disagree with you, Bob, but now is not the time.” Instead, Kramlich approached his partners with a unique offer. He proposed to personally finance Forethought himself, and “If it’s a winner, you guys get the proceeds. If it’s a loser, I’ll take it.” Chuck Newhall responded, “How can I turn that down?” Kramlich replied, “That’s my point.”

Over the next four months, Kramlich fed Forethought $60 thousand a month to cover payroll and costs, for a total of about $250 thousand. With his wife, Pam, they put several domestic plans and priorities on hold to manage this direct investment. The Kramlichs were putting Dick’s philosophy into practice, investing in Gaskins, his team, and his vision and passion for Presenter. As Kramlich later explained, “But if some guy at a desk, in the back of the place… has kept this place alive and you’re lucky enough to find that person… I’ll walk the plank for them.”

Kramlich’s trust quickly paid off. Apple was enamored of Filemaker and made a big investment in Forethought. There was no more need for Dick’s monthly check. And in 1987, Presenter finally came to the market under its new name: PowerPoint 1.0. Originally for the Macintosh, PowerPoint was a smash success, with Forethought booking millions of dollars of orders. Things accelerated quickly. Three months later, Microsoft purchased Forethought to get PowerPoint, its first acquisition. When Kramlich went to talk about returning his gains on the deal to his partners in NEA, Newhall cut him off, “Dick, you earned that. You ought to get it.” As Kramlich later explained, “That’s the way our partnership has always worked. That’s why it’s enduring. Because we do the right thing, we’ll do the fair thing. And we can be candid with each other.”

PowerPoint packaging. Microsoft Corporation, 1994. Jim Warren collection. CHM catalog number 102690902. Gift of Jim Warren.

Over the past decade, Dick and Pam Kramlich developed a strong connection with CHM. They provided significant support for the creation of the Museum’s exhibit Make Software: Change the World! With their Kramlich Art Foundation, Museum staff have benefitted from discussions and events at the intersection of media art, computer history, conservation, and presentation. Dick Kramlich participated in a four-part oral history for the Museum and always encouraged our work to preserve and interpret business history around venture investing.

Dick Kramlich’s passing is a blow for many individuals and communities, including the Museum’s. But our sympathies are greatest for Pam and the rest of their family, for whom his loss is immeasurable.

Pam and Dick Kramlich in 2019. Photo by Ryan Young.

View and read Dick Kramlich’s four-part CHM oral history:

Part 1: Video, Transcript

Part 2: Video, Transcript

Part 3: Video, Transcript

Part 4: Video, Transcript

See an earlier oral history, part of a series from the National Venture Capital Association (NVCA) now preserved at CHM, here.

Watch Dick Kramlich’s appearances at CHM:

Trailblazers of Venture Capital (2019)

Venture Capital in the Valley: Past, Present & Future (2011)

View and read oral histories of Dick Kramlich's NEA cofounders:

Charles Newhall: CHM Video, Transcript; NVCA Transcript

Frank Bonsal: CHM Video, Transcript; NVCA Transcript