This is the second post in an ongoing series about the making of the Computer History Museum’s Education Center.

From the beginning of the project, CHM leadership understood that embarking on the design of a new Education Center would require the input of multiple constituencies, both internal and external. On one level, CHM recognized that observing multiple users’ relationships to the intended space and earning their buy-in were critical in creating a space that would meet the needs of the very diverse communities they wanted the center to serve.

At the same time, the Museum’s leaders acknowledged that their own staff had concerns and expectations that would need to be recognized and addressed. CHM’s Education Department is only one of several internal constituencies who may conduct programming or events in the new space. Lauren Silver, CHM’s Vice President of Education and the Education Center project lead, stated:

At the outset of the project launch, Silver held numerous meetings with Education staff to help shape an initial vision for how the space might look and function. The goal was not to achieve consensus but rather to air everyone’s “implicit” visions. Not surprisingly, there were many diverse suggestions. Though staff were willing to be involved, Silver was concerned that once this input process was expanded to other CHM staff as well as community groups, her ability to both manage the project and objectively tease out and assess other viewpoints while having her own personal vision for the space could be challenging.

She and others within CHM recognized that in order to maximize engagements with constituents, a certain level of design and process expertise would be required. For a number of years, CHM President and CEO John Hollar and Dennis Boyle, a founding member and partner at the design firm IDEO, had been exploring ways for the two organizations to collaborate. As discussions around the new Education Center intensified, it was apparent that the right project had finally materialized. Having the buy-in and interest of both organizations led to CHM hiring IDEO to facilitate workshops with CHM staff and community groups to articulate and generate concepts for the new center.

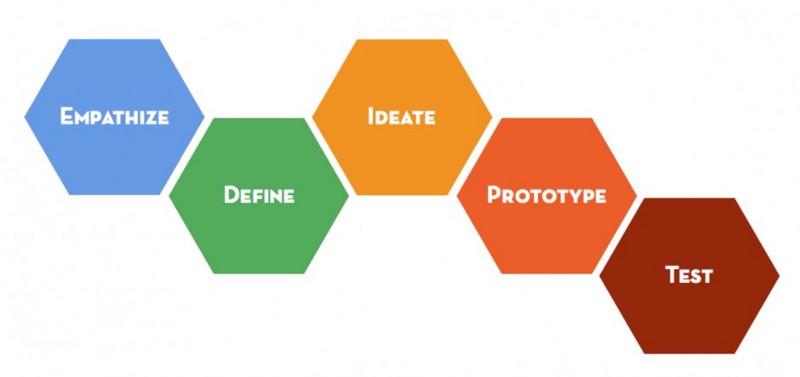

As mentioned in the previous blog, IDEO grounds its work in the human-centered design process. This approach encourages the inclusivity of multiple voices, assumes that all points of view are valid, and incorporates some ambiguity that often results in unanticipated surprises and innovation. When done well, a user-centered approach fuels the creation of products and ideas that resonate more deeply with an audience and ultimately drives engagement and growth.

During many of its engagements, IDEO spends a good deal of time helping the client envision the impossible as possible and imagine something new or novel. In the case of CHM, hearing many different voices and expectations, the IDEO team felt they needed to help Museum staff better understand the tradeoffs, and how to balance the many complex components that mattered to each of them in different ways. For the IDEO facilitators it was important to make staff comfortable talking about the intersection of space and programmatic concerns, to serve, as one IDEO staff member described it, as “spatial psychologists.”

In October 2016, IDEO conducted a kick-off meeting with about 25 CHM staff to introduce the user-centered design process and understand the staff’s issues and expectations for the space. When deciding who should participate, Silver made sure to invite staff representing different departments and functions across the Museum:

To prepare for the meeting, IDEO asked CHM staff to think about the following:

IDEO distilled information from the kickoff meeting to build the structure of subsequent co-creation sessions with members of the community (to be discussed in a subsequent blog). After completing the community sessions, IDEO asked CHM staff to respond to a broad set of images and symbols (also used with community groups) that corresponded to issues involved in the design of learning spaces; for example, “What is your preferred learning mode?” and “What is your dream classroom?” These images ranged from traditional to highly unconventional and were meant to prompt conversation and encourage diverse thinking. Both the process of arriving at answers and the answers themselves helped IDEO identify assumptions, requirements, and ambitions underlying staff’s ideas about how the space should look, feel, and function. By involving CHM in this manner, IDEO asked staff to make a kind of interpretive or imaginative jump.

According to the IDEO team, the inclusion of so many staff from CHM demonstrated the organization’s commitment to the project. Often client organizations are a level or so removed from their customers, but in this case, CHM staff were eager to be heard on issues of space design and functionality.

With no previous education space from which to draw ideas or inspiration, the project had a feeling of starting from a blank slate. Not only was there a multitude of ideas about how the education space should look, but also an equally open (and uncertain) lack of consensus and clarity among staff about curriculum, content, and pedagogical methodology. As a result, IDEO was faced with a chicken-or-the-egg dilemma: Should curricula drive the space or vice-versa? Faced with this dilemma, the IDEO team facilitated discussion and exercises aimed at helping staff imagine what and how they would teach in the new space. It soon became apparent that staff were concentrating more on curriculum development than on space and functional design. This drove the realization that IDEO’s ultimate design approach had to be open enough to accommodate many different curricula and methods of instruction.

What made this process alternately challenging and exciting for CHM staff was IDEO’s focus on “invisible” and abstract issues. Trying to imagine how a visitor feels when entering a space is not easy for many museum professionals, who typically think about space in more literal or physical ways. This exercise created an awareness that changing a space can have a huge impact on visitor interaction. In other words, by more clearly defining the kinds of visitor interactions the museum desires, staff can help designers create a space that better meets visitor goals.

Throughout the workshops, all participating CHM staff were given a voice and encouraged to articulate their concerns. At the beginning of the engagement, IDEO experienced some skepticism and pushback from CHM staff — not everyone bought into the process. By the end of the engagement, however, IDEO staff observed that CHM staff (even some of the harshest critics) appeared to be much more invested. Dialogue focused more on identifying common solutions and ideas than protecting individual turf. Achieving this level of buy-in in just five weeks was enormous. Project architect Mark Horton believes there is tremendous value in this type of direct and open engagement with staff:

IDEO believes that this kind of sustainable education can happen “underneath,” where methods applied during an engagement can be harnessed for other purposes within the Museum and for engaging new and diverse audiences. A number of CHM staff have remarked that while the design thinking process was difficult at first, they have developed an appreciation for it and will be looking for ways to adapt it for use within their departments and with constituent groups. Lauren Silver believes that it was important to have an outside agency like IDEO facilitate a process to challenge staff and create a safe and nonjudgmental space for an open flow of ideas:

Rendering of CHM Education Center — Mark Horton/Architecture

These discussions and workshops demonstrated the power of collaborative design thinking. They created a process of collective inquiry and imagination in which diverse actors (CHM staff, architect, teachers, community constituents) jointly explore and define a problem and together develop and evaluate more daring and less predictable solutions. All participants were able to express and share their experiences, push back, reflect, discuss, and negotiate their roles and interests, and in the end jointly envision and realize positive change.

While IDEO staff were proud of the final design, they were particularly gratified when “the whole engagement catalyzed” as the process was coming to a close. Through the design process, IDEO was able to synthesize what all participants had to say and encouraged dialogue (sometimes difficult) among CHM staff. This made the final design concept representative, inclusive, and tangible. It was an accomplishment to provide a number of design directions that staff could either agree with in total or work collectively with the project architect to refine.

As CHM continues to think more deeply about use of space and adopts new methods of learning and instruction, the Education Center can change as well. User-centered design assumes a necessary degree of fluidity and adaptability, underlying the understanding that a community’s needs and expectations are not static and will evolve.

Mark Horton, charged with taking IDEO’s education center design concept and working with CHM staff to make it a reality, feels that his task has been made much easier as a result of these user-centered staff workshops.