ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, December 12-15, 1983, Boston The ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI) academic conference is considered the most prestigious in the field of human–computer interaction. CHI has been held annually since 1982 and attracts thousands of international attendees.

The vibrant social processes of science are dramatically visible at conferences, workshops, seminars, and other gatherings of researchers. The main events are typically presentations by invited senior speakers or aspiring young researchers who have won the approval of reviewers. The audience members listen and watch the slides, then respond with supportive applause or challenging questions. Breaks, meals, and receptions offer major social possibilities, enabling young scholars to meet prominent leaders, colleagues to reconnect, and advocates of new directions to confront those who stick to traditional paths.

Capturing these social processes has been my challenge for 30+ years. Researchers can be subdued, but they can also be enthusiastic, disagreeable, or confused. I tried to track an idea’s movement from one mind to another, record a speaker’s enthusiasm or capture a spirited confrontation. These challenges motivated my photography of computing professionals from my grad student days when I sought out respected leaders and acknowledged pioneers. Even now that challenge remains strong as I continue photographing long-term trusted collaborators or rising stars whose work seems promising.

Ideas leave no trace, but the facial expressions and body language that they evoke reveal the intense human engagement in scientific exploration. Some scientists are known for their passionate presentations or confrontational questions, while others are famously anxious, cheerful, or angry. Cameras cannot capture ideas, but the emotional reactions to a fresh idea or skepticism about a surprising result yield compelling images. Ideas are like neutrinos, invisible except for the impact they make on others.

If I were to create a pattern language of scientific exchanges it might include these themes:

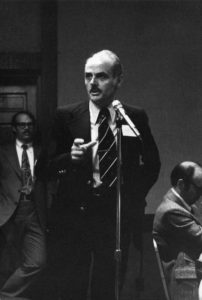

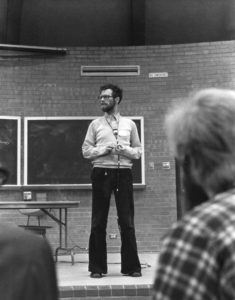

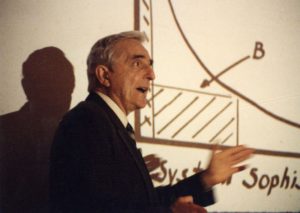

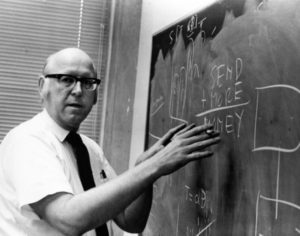

Standup lecture: A featured speaker may address a seminar table with ten attendees or a conference hall with thousands. Capturing the lecturer shows only part of the story, photographing the faces of listeners shows another part, but getting both is a challenge. The standard composition shows the backs of the audience members with the speaker in the distance. Blackboard “chalk talks” have given way to slide presentations, often separating the speaker from the content. Other challenges are the distraction of audience members looking down at laptops or mobile devices.

Seminar discussion: Smaller workshops, professional panels, or working research groups offer good opportunities to show the faces, hands, and body language for all participants. I try to capture spontaneous discussions, but often have to wait till participants are appropriately facing each other and appear engaged.

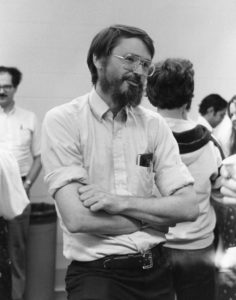

Hallway encounters: Pairs and small groups will often gather in exhibition halls, receptions, or at posters. The lively discussions make for good photographic opportunities because the participants are often intensely engaged with ideas, self-promotion, or personal story telling.

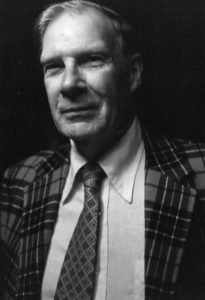

Posed portraits: Getting a memorable photo of an individual, author team, or research group often happens when I make a specific request, such as “will you honor me with a photo?” Getting researchers to pose in their office, with their award, or holding their new book often makes for a good photo. Their natural pride, willingness to smile, and good eye-contact contribute to a strong image.

Many variations are possible, keeping me alert to new possibilities. I favor a wide angle lens to be close to my subjects, but a telephoto helps capture speakers on a stage. I’m reluctant to use flash since it disrupts activities and produces a more staged image.

I edit my photos to remove poor quality or redundant images, then crop to improve layouts, but rarely change brightness, and never do pixel-level editing, except for occasional red-eye removal.

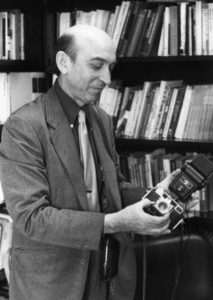

My youthful interest in photography was stimulated by my uncle, the world-famous photojournalist David Seymour (1911-1956), shown here, who was a co-founder, with Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and George Rodger, of the Magnum photo agency. He and his colleagues believed that photos could change the world, and sometimes they succeeded. I considered a career in photography, but was lured to computing, happily keeping photography as a hobby.

The shift from black & white photos to color negatives was big change, as was my change over to digital photography during 1999. While early digital images were lower quality, modern digital cameras produce sharp images, even in low light. The compact digital cameras enable me to always have a camera with me and to be less intrusive when I take photos. However, a large camera with good telephoto lens produces substantially better images. Other benefits of digital photography include the ease of sending email copies to my subjects and the capacity to tag photos with names.

My photos of professional events grow more valuable over time as my colleagues become prominent. Occasionally, colleagues call on me to send them photos from past encounters or I make collections of photos for retirement parties. In these situations I profit from the long-ago investment in tagging. A memorable use of my photos was to make an 8-page 25-year retrospective of the ACM SIGCHI conference series that included 100 photos. This retrospective was appreciated for the youthful pictures of senior leaders, showing the change in hair and clothing styles, and reminding viewers of how fast computing, slide presentation, and cell phone technologies had changed.

In the past, there were occasionally other photographers at an event, but now the profusion of photographers is much greater. Within minutes photo sharing and social networking sites have photos of events, but the quality varies greatly and tagging is rare. I hope my 20,000+ photos capture the emergence of computer science and especially human-computer interaction and information visualization.

I continue to take, tag, and organize my photos for my personal satisfaction, but also in the belief that they will be interesting and valuable to others in the near and more distant future. Getting a great photo of a respected colleague delivering a lecture or two young researchers arguing still satisfies and challenges me.

Fred Brooks (b. 1931) remains a leader in software engineering and computer graphics. His 1975 book The Mythical Man Month remained a best seller for several decades because of its insight-filled comments about the social processes involved in software development. He received the National Medal of Technology in 1985 and the ACM Turing Award in 1999. His smiling disposition and vigorous lecturing style were an attraction for me.

Edgar F. “Ted” Codd (1923-2003) was a memorable character whose Royal Air Force career from World War II, in addition to his British accent, gave him a distinctive style, . I found him always polite and very engaging, even while he was a persistent promoter of his radical idea of a mathematically elegant relational database model. His series of papers and participation in the famous May 1974 debate at the ACM SIGMOD conference helped push IBM and others to implement the relational model in commercial systems, which became the dominant data model.

Edsger Dykstra (1930-2002) spoke sharply and wrote forcefully about improving programming languages and raising the quality of programming by encouraging proof-like approaches to software development. He moved from Holland to the University of Texas at Austin in 1984. I attended a 1974 week-long course in which he laid out his philosophy, providing lucid examples at the blackboard. I tried to convince him of the value of psychological studies of programmer performance to understand their cognitive methods, but he was only mildly interested. I always appreciated the clarity of his thinking and his calm presentation style.

Ed Feigenbaum (b. 1936) is a Fellow of the Computer History Museum “for his pioneering work in artificial intelligence and expert systems.” As a Stanford University professor and chief scientist for the US Air Force, he had great impact and received the ACM Turing Award in 1994 and the IEEE Computer Pioneer Award in 2013. He was a thoughtful intellectual leader, whose warm smile and gentle style made him an excellent subject for my portraits. This characteristic smile was at a lecture visit to the University of Maryland in January 1995.

Doug Engelbart (1925-2013) was an early hero who had promoted intelligence augmentation (IA) in place of artificial intelligence (AI). His efforts to help knowledge workers be more effective led to his historic demonstration in 1968, in which he showed a large wooden mouse for pointing, chord keyboard for text entry, file sharing, and collaborative methods such as videoconferencing. We met at the 1987 Hypertext conference, but I most remember our 1998 encounters when he received the first Lifetime Achievement Award at the ACM SIGCHI (Special Interest Group in Computer Human Interaction) Conference. He tearfully told us that he greatly appreciated the recognition, since he felt his work had been rejected by many. His gentle soft-spoken style was very different. As his work spread, especially creation of the mouse, he received worldwide acclaim.

Bill Gates (b. 1955) is one of the world’s most familiar names and influential personalities, certainly within the world of computing. I first photographed him as a young businessman visiting the University of Maryland, but later sessions were at public talks at Georgetown University, the Microsoft Faculty Summit, and at a Washington, DC policy event. He always impressed me as a thoughtful and knowledgeable professional, even when I disagreed with his positions or the actions of his company.

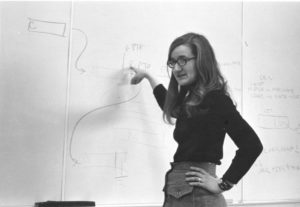

Grace Hopper (1906-1992) was a pioneering computer scientist and early programmer who developed the first compiler and influenced the development of COBOL. She was devoted to her U.S. Navy career, rising to the rank of Rear Admiral. Her feisty style was engaging, making for great talks, and great photos. I still have the piece of wire she handed out to attendees to remind us of how far electricity traveled in a nanosecond. She remains an inspiration to men and women computer scientists through her work and the annual Grace Hopper Conference.

Ken E. Iverson (1920-2004) was an independent thinker who created APL (A Programming Language), based on a distinctive mathematical notation for array manipulation. This novel approach required special characters for each operator but resulted in very compact, yet powerful programs. A common game was to accomplish a task with as few characters as possible, resulting in some clever, but hard to decipher programs.

Richard Hamming (1915-1998) was one of my first professors of computer science as an undergraduate at City College of New York. He would come in from his job at Bell Labs in New Jersey to teach. I remember taking two semesters with him, in which he covered only material that he invented, such as the Hamming Code and numerical analysis algorithms. This memory may be an exaggeration, but he was an impressive scholar and effective teacher. I was pleased to meet him at conferences years later and appreciated the warm smile he greeted me with for this portrait.

Brian Kernighan (b. 1942) helped raise expectations of what it meant to be a great programmer. He took the idea from my book with Charles Kreitzberg, The Elements of Fortran Style, and generalized it into the widely used The Elements of Programming Style. We met occasionally to cheerfully trade notes about what made for great programs and how to teach good style. This photo was at a lecture visit to Univ. of Maryland in October 1982.

Ken Knowlton (b. 1931) was an early leader in computer graphics who worked at Bell Labs. He explored the artistic possibilities of bit-mapped images ranging from portraits to a reclining nude, which was a provocative idea in 1967. This photo was at the ACM March 1976 Conference.

J.C.R. Licklider (1915-1990), known as “Lick,” was a computer visionary who had great influence on research directions though his leadership at ARPA and then MIT’s Project MAC. He was soft spoken, but clear in promoting a human-centered approach to interactive systems design. His famed 1960 essay on “Man-Computer Symbiosis” made clear that users “will set the goals, formulate the hypotheses, determine the criteria, and perform the evaluations. Computing machines will do the routinizable work that must be done to prepare the way for insights and decisions in technical and scientific thinking.” I enjoyed his visit to our group at the University of Maryland in April 1979, when I took this photo, and soon after appreciated his kindness as my host to speak at MIT.

Andries van Dam (b. 1938) has taught a remarkable number of students who have gone on to successful careers, especially as chairs of computer science departments. He is much appreciated by his students and colleagues like me for his intensity, emotional connectedness, and professional generosity. His devotion to 3D technology and user interfaces led to the highly influential book, Fundamentals of Interactive Computer Graphics, written with James Foley in 1984, with later editions in English and other languages. He’s also rightly proud of his five decade long efforts on hypertext/hypermedia systems.

Allen Newell (1927-1992) was an inspirational hero whom I visited at the Carnegie Institute of Technology to plan my graduate work in 1968. However, the Viet Nam War meant that my draft board would not grant a deferral for me to accept a graduate fellowship to study with Newell. I remained in touch with him, sent him my papers, and was honored to write a review of his co-authored book on The Psychology of Human-Computer Interaction. One of my professional highlights was during Newell’s 1985 keynote for the ACM SIGCHI conference, when he cited my 1980 book Software Psychology as being an important influence on him.

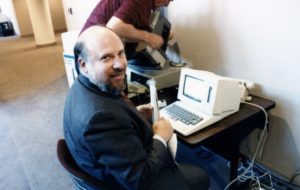

Jef Raskin (1943-2005) was a creative designer whose visionary ideas laid the foundation for the Apple Macintosh. His persistent promotion of advanced user interface designs was apparent in his 2000 book The Humane Interface. His eagerness to show his ideas and do demos helped spread his ideas, but sometimes his enthusiasm was overwhelming.

Diane C. Pirog Smith (b. 1944) was an early researcher in database theory as the relational model was gaining visibility. Her work, while at the Univ. of Utah, showed strong theory skills coupled with an understanding of how commercial applications worked. These skills made her a worthy contributor to data models, query languages, design and standards efforts.

Nicholas Negroponte (b. 1943) visionary thoughts and writings were admirably bold, but often controversial. To his credit he was able to raise funds to implement his ideas and energy to test them in real world situations from African tents to Asian classrooms. His most well-known idea, One Laptop Per Child (OLPC), resulted in an inexpensive small computer that was to be distributed to millions of children, but controversy ensued about its impact. His leadership of the MIT Media Lab produced an adventurous community with many bold ideas. His visionary ideas were captivating and admirable, but I found his technology-centered concepts might have proved more successful if he more directly addressed issues of how teachers, parents, and children learn.

Terry Winograd (b. 1946) began his career with a highly influential dissertation, “Understanding Natural Language,” in which he demonstrated success in dealing with a limited set of nouns and verbs related to his “blocks world.” I wrote critically about the utility of this work in my 1980 book Software Psychology, so I was pleased that Winograd’s 1987 book, Understanding Computers and Cognition, with Flores reported that “computers can’t understand natural language.” From then on we developed a warm collegial relationship, especially as I greatly respected and learned from his political activism and commitment to social causes, as well as his excellent research in human-computer interaction and collaborative systems. His masterful lectures were always an attraction for me, such as this one at the first ACM Conference on Computer Supported Collaborative Work in 1986.

Lofti Zadeh (b. 1921) was famous for “fuzzy logic,” but his clear thinking and mathematical prowess were apparent. His ideas had widespread impact, influencing computer scientists, neuroscientists, and humanists who appreciated his devotion to ambiguity and uncertainty. I visited his UC-Berkeley office, which was a 3D maze packed with shelves containing his publications going all the way to the ceiling. He is one of the few computer scientists who was also a serious photographer. He came to visit me at the University of Maryland and we enjoyed taking pictures of each other.

Jean Sammet (b. 1928) was an early contributor to programming language development, especially for business-oriented programming. She was my manager when I took a sabbatical working at IBM’s Federal Systems Division in 1982. I enjoyed her energetic outspoken style, often accompanied by a big smile, but she was also known for her cutting comments. She was a can-do leader who became the first woman ACM President (1974-1976). This photo was taken on a speaking visit to the Univ. of Maryland in March 1979.