This is the third post in an ongoing series about the making of the Computer History Museum’s Education Center.

Museum construction projects can be extremely complex, and as is often the case, these projects may not go as planned. The Computer History Museum’s (CHM) Education Center initiative is a prime example of how unexpected circumstances can actually strengthen a project, rather than hindering it.

After completion of the IDEO design consultation last fall and modification of that design by the project architect in early 2017, the Education Center project was on a fast track. The opening had been targeted for September 2017, which meant that requisite funding needed to be secured and the center’s AV, other technology, furniture, storage, acoustics, ceilings, build-outs, activities, exhibits, and volunteer training had to be decided and finalized all within four to five months. The aggressive timeline prompted discussion about possible trade-offs: Would the project benefit from scaling back to prioritize speed of execution? Or should the schedule be adjusted to allow more time for fundraising and design development, ensuring that the finished center would exemplify its original vision and goals?

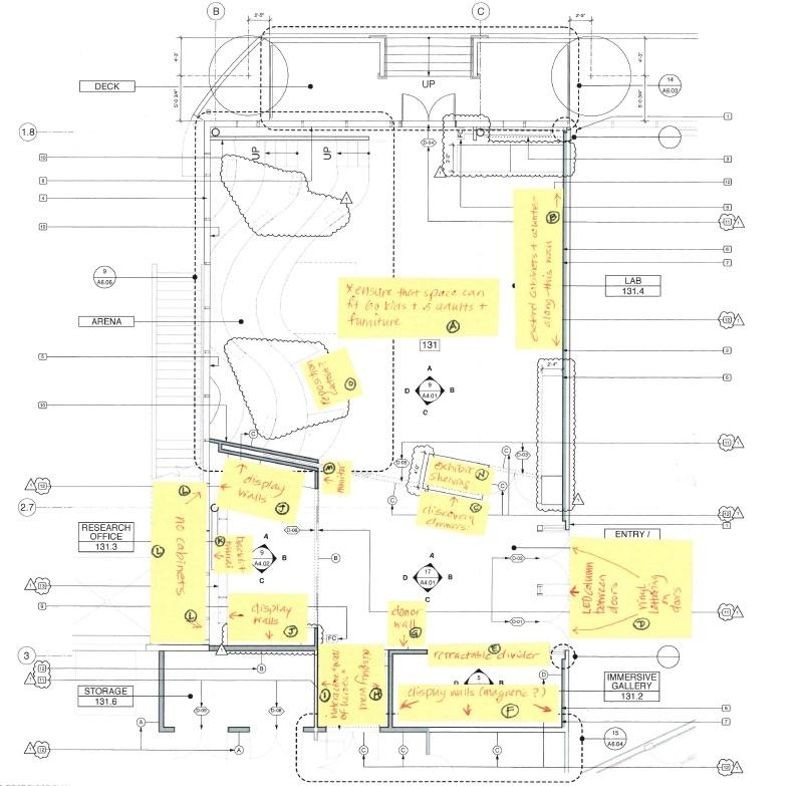

Annotated plan from Mark Horton/Architecture.

Ultimately, CHM decided to extend the timeline. Fortunately, a collaborative cross-departmental project team (education, exhibits, development, facilities, finance, architect) had been in place since the initial design phase, so they were prepared to address both the expected and unexpected. And the team had anticipated from the beginning the need for a “value engineering” phase during which hard choices would have to be made in order to ensure a more feasible, affordable, and timely final product. Conversations such as these are common for large institutional expansions. Museums and other nonprofits will also recognize them as part of their dual bottom line, balancing mission impact with fiscal responsibility and operational realities.

Though the delay might seem problematic for CHM, it provided staff with an opportunity to improve the quality of educational programming for the center.

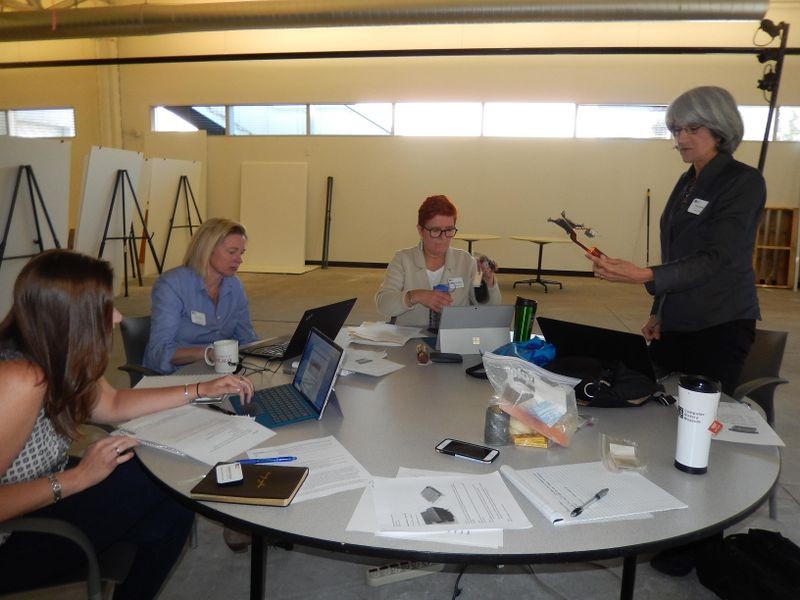

Interpretive Planner Emily Routman leads a development workshop with VP of Collections and Exhibitions Kirsten Tashev and Education’s Katharina McAllister and Stephanie Corrigan about “Discovery Drawers,” an upcoming artifact-focused activity to be featured in the Museum’s Education Center.

Working to meet the original completion deadline, Education Department staff were concerned that they might need to open the center in a less than finished state, with many of the activities in prototype phase rather than being completely developed and tested. Given the multitude of tasks necessary just to have the space physically ready for visitors, staff simply did not have the requisite time to conduct the essential background research, thinking, and organizing to test out different concepts and ideas for center exhibits and activities. Also, the majority of CHM Education staff have program backgrounds, so exhibit design and prototyping was new territory for most of them.

With the extended timeline, Silver and her staff now had the opportunity to design and evaluate the content of the center in a more deliberate and thoughtful manner. Silver hoped that her staff could own this process, but the need for expertise in exhibit design and activity prototyping—and efficiently guiding a team through this detailed and intense phase—still remained. Though CHM had skilled exhibit designers on staff, Silver wanted to bring in an expert who would combine both exhibit design and interpretation, as well as facilitate the process, in much the same way IDEO had been hired to guide CHM staff and build consensus around the Education Center’s initial conceptualization and design.

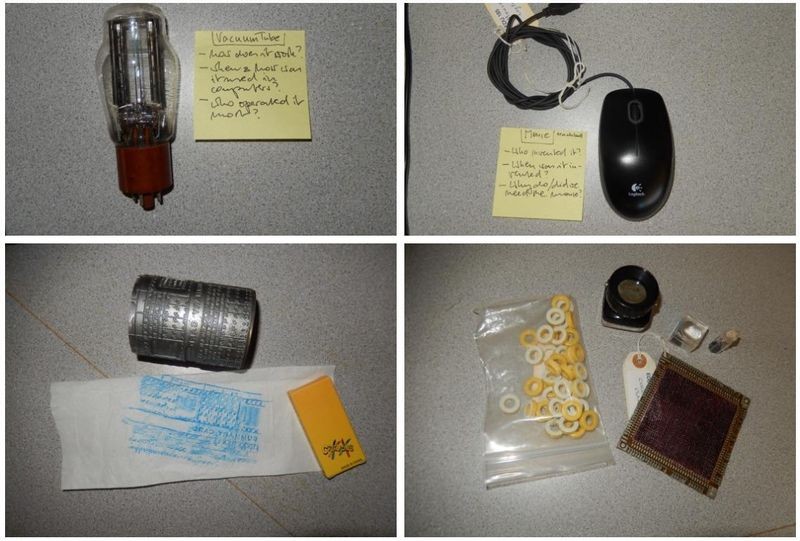

Participants in the Discovery Drawers workshop chose objects and discussed visitor engagement around those objects. Goals for the activity included 1) make technology relatable and accessible, 2) highlight the diverse people who play a role in creating and using technology, and 3) encourage a creative approach to looking at and learning with and about technology.

Silver contacted Emily Routman, a museum exhibit and education consultant, who had worked with CHM staff in the past on exhibit design and implementation. Not only did Routman have familiarity with the Museum itself (allowing her to bridge the know-how of CHM’s exhibit team with that of Education), but she also brought the requisite experience Silver was looking for, specifically in guiding teams in designing and prototyping drop-in interactive exhibits and hands-on activities. She was also someone who could facilitate the process of building staff capacity to conduct this kind of work on their own.

For Routman, this engagement represented a welcome opportunity to work toward a goal where the educational experience, as opposed to the exhibit content, was the primary consideration.

Museum visitors test the Education Center’s first prototype activity: taking apart (and putting back together) a computer.

Going into the process, Routman was excited to help realize an innovative educational space that would afford the visitor diverse educational and sensory experiences. She appreciated the emphasis on the user-centered design process and how that process was rooted in learning principles, resulting in intentional support for social and active learning strategies. The Education team hoped to create an inviting space that would accommodate individual and group exploration, incorporating both facilitated and nonfacilitated experiences.

Before the timeline was extended, the team’s goal had been to have at least one well-developed activity ready for visitors when the center opened. They had developed preliminary ideas for interactive exhibits; after a series of meetings to review options, one was selected—taking apart a computer. Even after the timeline changed, this remained the activity of choice because of its historical relevance, its potential to work in both a nonfacilitated and facilitated manner, and because it presented many rich ideas for extensions into other programming areas.

The fact that the activity had to succeed with minimal supervision made it especially challenging. Routman’s expertise was valuable in helping Education staff work through the many questions and considerations. The extended schedule gave the team more time for planning and testing.

CHM staff and visitors benefit from the expertise of a cadre of uniquely qualified volunteers, many of them current and former engineers from some of Silicon Valley’s leading technology companies. For the Education Department, the volunteers’ extensive technical knowledge and experience provides a valuable sounding board for program and activity development. For the Education Center, volunteers helped identify artifacts that would work best for particular activities and contributed ideas for making those activities interesting and accessible to visitors. Their involvement extended the inclusive process that was initiated during the IDEO-facilitated workshops last year and added entertainment value.

CHM docents, like Bud Warashina (left) and Toni Harvey (right), bring essential knowledge and expertise that enhance the Museum’s visitor experience.

During the work sessions, the volunteers echoed many of the same concerns and questions about taking a computer apart that Education staff had already considered. Hearing this was validating for staff because it meant they were thinking about the right things in developing this activity for the public. Volunteers will play an important role in the Education Center, as they will make up a major staffing component, often overseeing activities and answering visitors’ questions. In effect, the rescheduled opening provided more concentrated time for involving and engaging volunteers in the design and development process.

Through careful preparation and foresight, CHM Education staff successfully adapted to unexpected changes in the Education Center project schedule. By working collaboratively toward a shared goal, team members across the organization deepened working relationships, took on new responsibilities, and adopted innovative methods for designing activities to enhance the educational experience of the visitor. The process of planning for the new Education Center has demonstrated that leaning into the unexpected can often uncover a wealth of unanticipated opportunities.

As this article was being researched, CHM’s Development Department reported that they have secured the funding necessary to begin construction of the Education Center in the summer of 2018.