Recently, Google’s Sergey Brin made waves—or at least invoked a collective eye-roll—when he termed current smartphone technology “emasculating” and suggested Google glass as an antidote. Offering a pair of computer-infused glasses as the solution to the problem of technological emasculation seems as though it might be the punchline to a joke. But Brin’s offhanded comment provoked enormous ire because the history of computing, and indeed computing’s present, is rife with examples of attempts to gender technologies in ham-handed and often offensive ways.

Envisioning technologies that have very little to do with one gender or the other as somehow being masculine or feminine has a long pedigree. The needs of business, government, or even consumers, often result in technologies that become understood as somehow being resoundingly masculine-coded or feminine-coded. Take, for example, early computer programming:

Hardware-dependent and labor-intensive, early programming required understanding not only the way the programmatic instructions worked but also how the hardware of the machine functioned–right down to the wiring. Grace Hopper, for instance, famously sped up programming runs on the stodgy, electromechanical Mark I by pulling out rows of relays for decimal places she didn’t need. Indeed, Hopper’s popularization of the term computer “bug” came from her programmer’s familiarity with the hardware: a moth got wedged inside one of the Mark II’s relays and her program wouldn’t work until literally removed the bug.

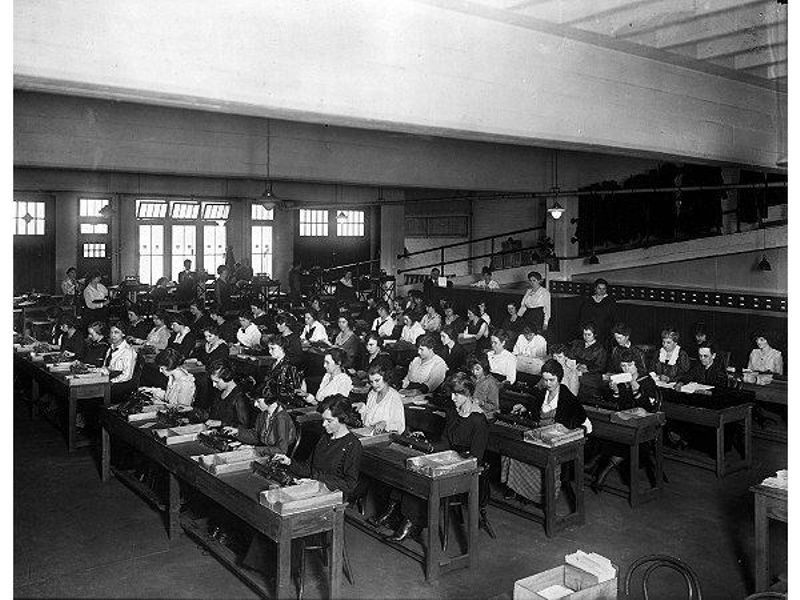

But today, working with hardware and programming are both coded masculine for the most part. Why then was this work coded feminine throughout the 1940s and 1950s? The answer to that lies in earlier decades, when women human computers were asked to produce seafaring (and warfaring) tables for the British government. Though these tables had previously been made by amateur or retired men, the need for faster and more accurate table-making created a new class of workers and a new system of table production by the early 20th century. Young women working with desktop accounting machines were organized into what could be described as calculation factories.

Women workers in a calculation “factory,” 1930s. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

When the machines for this mathematical work became electronic, the same work force carried over, with the same employer expectation of cheap, pliant labor. Wrote one British government manager, referring to women machine workers: “Besides manual dexterity there is a necessary aptitude required to be content to sit at a desk and do a boring job.” Young women, having few prospects in white collar work in the mid-20th century were thus made to be content with such jobs. Indeed, L.J. Comrie, a New Zealander by birth who brought mechanized, systematized computing to Britain and the world, saw women as ideal candidates for his system. The fact that women’s rates of unionization were lower than men workers also enhanced their attractiveness in the eyes of employers. In the same way that young men and women were sucked into factories under industrialization, so too were young women brought into the “industrializing” office.

Where women could be used to do work considered beneath men (or where they could be used as cheap labor to undercut men’s wages) they were, resulting in jobs that became feminized–in other words, perceived as deskilled and thus given mostly to women. Programming was one such area until 1960s-era watersheds in the popularization of management science gave employers a new vision: one of technocratic control through young, male manager-programmers. But at the same time, hardware jobs stayed feminized: through the 1960s, IBM UK, for example, measured its manufacturing and testing in “girl hours” rather than man hours.

But gender norms, just like technologies, are constantly changing. The assignment of certain traits and ideals to one sex or the other is a historical process in the same way that the development of different techniques for storing data is a historical process: not all will be appropriate for all times or contexts. And so it was with programming. Today, only about a quarter of US computer professionals are women, a number that has not seen much improvement for the past 30 years. Which leads us to the problem of “brogramming”—and also sheds light on the backlash against Brin’s “emasculation” comments.

A satirical riff on the “fake geek girl” meme that castigates women and girls as “posers” for professing interest in nerdy pursuits. by Haylee Fisher (@haylee_fisher)

Last year, Mother Jones magazine did an article about Silicon Valley’s “brogrammer problem” and many other news sources picked up the story (see here for an analysis of that coverage). Brogrammers—sexist, fratty, beer-swilling young guys who partied hard in between coding marathons—were a self-conscious reaction to the stereotype of programmers as nerdy, pasty, bespectacled men (or perhaps bearded, potbellied, sandal-clad men). Surprisingly enough, this new ideal did not go over well with the ladies. Or even with many of the aforementioned pasty and beardy nerds. The brogrammer ideal was to “crush code” and be productive in newer, cooler ways. But the reality was that brogramming was a retread of every other nerd stereotype that’s come down the pike; categories that try to consolidate technical authority by marrying technical proficiency with socio-cultural prestige of one sort or the other. The problem is that this prestige is almost always rooted in masculinity, aggressive heteronormativity, and usually whiteness in the Anglo-American context. In other words, it further privileges those already on top.

But as each sexist iteration of nerd-dom has evolved, there have been more and more powerful backlashes. Now, extensive networks of feminist practitioners within technology fields combat sexist and racist discourses and assumptions on a daily basis. Twitter networks formed around hashtags like #changetheratio and #onereasonwhy, for instance, specifically take on the issue of women’s visibility and advancement in STEM fields. The “one reason why” campaign points out the particular ways in which sexism still exists, and still ruins lives and career prospects on a daily basis. It shows how the reverberations of institutionalized sexism continue to shape women’s daily experiences; and it shows how individuals’ actions leverage and re-deploy (intentionally or not) this history of othering women in technology, to the detriment of coworkers and potential entrants to the field. For instance, when Adria Richards recently spoke out about sexism at technology conferences, her actions provoked a disproportionate a cyberbullying campaignwhich ultimately cost her her job.

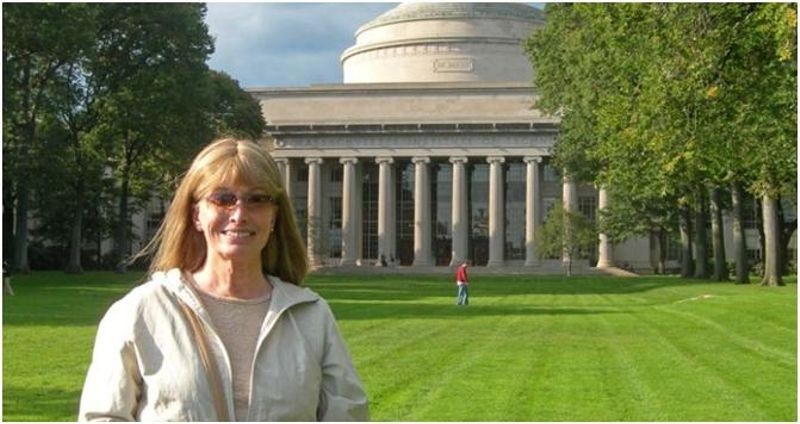

Lynn Conway at MIT in 2008, commemorating the VLSI design course she launched there 30 years before.

In honor of women’s history month, it seems appropriate to include a few specific examples of women who have fought these battles, and won. In the 1960s, pioneering chip design researcher Lynn Conway made breakthroughs at IBM that are still recognized as historically important today. For years she got no credit because she was drummed out of IBM for being transgender. Only decades later could she take credit for her early achievements, because doing so once again outed her as a MTF transsexual in a field that had rejected her for that years before.

Professor Conway’s example shows, in stark terms, the stakes involved in fitting into gendered patterns and preconceptions, and the literal calamity that can strike when one refuses to play one’s expected role. Conway’s mistreatment is more than simply an artifact of the past. Her life experiences over the decades make clear the enormous lengths to which all practitioners in male-dominated fields must go to enact gender “properly”—in line with the expectations or perceived expectations of the least tolerant among the most powerful in the field—or otherwise risk ruin. In fact, IBM did not adopt an antidiscrimination policy for “gender identity and expression” until 2002 even though the company has had one for sexual orientation since 1984. Conway, however, has risen to the top of the field despite her earlier treatment at IBM.

Stepping out of one’s socially-sanctioned role and being harshly punished for it also echoes in the more recent treatment of Anita Sarkeesian, who ran up against a similar situation of gendered harassment and hate after proposing a feminist videogame project on Kickstarter. Sarkeesian’s project, however, ended up getting vastly more funding and support as a result of her grace in weathering those attacks. Relatedly, the persistent (and even escalating) practice at tech conferences objectifying women as a marketing device has recently come in for renewed criticism. This month, the attendees of the SXSW conference have made a concerted effort to discuss and catalog the continuing problems there and highlight how these practices alienate many women working in high technology.

The brogrammer ideal strums the century-old theme that women workers are inherently less robust, less competent, and less able to succeed in difficult, high pressure work. That they may belong in startups and at tech conferences as entertainment, but not as real workers. The main insight that can be gleaned from the phenomenon of “brogramming” is how powerful discourse and language can be in constructing the reality of people’s daily lives, right down to the places they feel comfortable living and working. Through brogrammers and their output might seem like a kind of vaporware, it’s worth remembering that just like compelling vaporware can mobilize millions of dollars in angel investments, brogrammers can mobilize thousands of people away from high technology pursuits—simply by existing as an idealized identity.

Even if brogrammers don’t really crowd the cubicles of Silicon Valley they can still do enormous damage, because perception and stereotypes actually construct reality rather than simply reflecting it. But preventing such damage can also be a matter of discourse. And the many online spaces where feminists–men, women, and genderqueer alike–are now loudly making their presence, history, and opinions known are challenging these stereotypes. I’d like to thank the Computer History Museum for joining that effort by giving me this space to talk about these issues, how they’ve changed over time, and how they continue to evolve.