With their hearing aids, the hard of hearing have consistently been among the earliest commercial adopters of new electronic technologies, as historian Mara Mills has shown. The histories of disability and of technology interweave in many different, fascinating, and important ways. The desire among many of the hard of hearing for assistive technology—hearing aids—has been a significant force in the history of electronics.

Mara Mills, “Hearing Aids and the History of Electronics Miniaturization,” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, April-June 2011, pp. 24-44.

In the early years of the 20th century, the first hearing aids to use electricity were based on telephone technology. Many users found them terribly conspicuous, yearning for something smaller, more comfortable, and far less visible. The advent of the vacuum tube introduced the age of electronics, opening new possibilities for creating, altering, and transmitting sound.

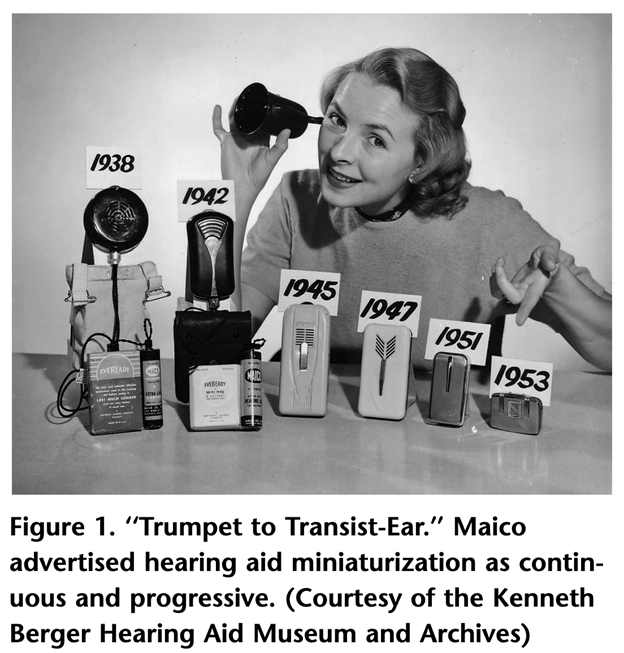

Hearing aid manufacturers quickly adopted the new electronics technology, using tubes to amplify sound. They, along with the makers of portable radio sets, had an insatiable demand for smaller tubes that were more robust and less power hungry. The electronics industry responded, and the smaller tubes enabled miniaturized, less conspicuous, hearing aids.

Throughout the Second World War, military demands further drove the miniaturization of electronics, with ultra-miniature vacuum tubes, and the intensive development of printed circuitry. After the war, hearing aid manufacturers quickly used these developments to further their own decades-long efforts at miniaturization.

At the end of the 1940s, an incredibly important development in the history of electronics occurred: the invention of the transistor. The transistor could perform the electronic functions of a vacuum tube but following an entirely different principle. Instead of flows of electrons through the vacuum in the interior of a tube, transistors worked by controlling the flows of electrons through solid materials called “semiconductors.” With this new principle, transistors could be made much smaller than vacuum tubes, requiring far less power. Eventually, they were made to be extremely reliable as well.

While early transistors were dedicated to telecommunications and military production, the earliest commercial uses of transistors were in hearing aids, in keeping with the hard of hearing as the earliest of adopters of new electronics technology and miniaturization. Perhaps the world’s foremost collector of transistors and related objects, Jack Ward, recently donated to the Computer History Museum two very early hearing aids that employed transistors: the Sonotone Model 1010 and the Telex Model 954.

Sonotone 1010 donated by Jack Ward to the Computer History Museum. Photo by Aurora Tucker.

Inside the Sonotone 1010 donated by Jack Ward to the Computer History Museum. Photo by Aurora Tucker.

The Telex 954 donated by Jack Ward to the Computer History Museum. Photograph by Aurora Tucker.

While the transistor was first demonstrated in a laboratory at the Bell Telephone Laboratories at the very end of 1947, the Sonotone appeared on the market in December 1952. It was the first commercial product to use transistors. The Telex Model 954 appeared somewhat later, in December 1954, and, like the Sonotone 1010, used two miniature vacuum tubes along with one transistor to provide the amplification of sound. CHM is honored to have these incredible devices in its collection, preserving artifacts so important to both disability history and the history of electronics.

Mara Mills, “Hearing Aids and the History of Electronics Miniaturization,” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, April–June 2011, pp. 24-44.

Jack Ward’s Transistor Museum.