This is part one of two of CHM’s High School Internship Program blog series, compiled and written by an editorial taskforce of the Museum’s 2016 interns. Read part two here.

The Computer History Museum inspires people from all over the world every day, and this summer, the Museum became a place where 18 high school students engaged with history, explored their passions, and discovered their strengths. When I joined CHM in 2014, I developed the High School Internship Program to promote a spirit of intergenerational learning at the Museum. I wanted to create a community of young advocates for CHM who could share their enthusiasm for computer history with our visitors and grow as communicators and critical thinkers.

Me (far right) with CHM’s 2016 high school interns during our field trip to Google.

While reflecting on the first year of the program, I saw an opportunity to create a community of peer learning and invited four students from the 2015 cohort to serve as mentors for the new interns. The mentors supported their team of students, offering feedback and guidance throughout the summer.

The program began in June with three weeks of training, during which the interns met staff members, researched the artifacts and stories in Revolution: The First 2000 Years of Computing, and learned how to communicate with visitors. For the remaining six weeks, the interns staffed the Exploration Station, a hands-on table in the lobby with artifacts that visitors can interact with and touch, and served as Gallery Interpreters, leading discussions and answering questions throughout Revolution. Meanwhile, their mentors were leading Family Tours in Revolution four times a week and engaging young visitors in an exploration of computer history.

The summer 2016 interns have interests ranging from creative writing to airplane mechanics, but what binds them together is their genuine dedication to helping others, and willingness to learn. They are an incredibly talented group of young people who have shown me—and CHM visitors—just how far-reaching and influential the stories of the Information Age can be.

When I was a teenager, I had the opportunity to intern with my town’s local government, and at a young age, found myself in situations where my voice was heard and I could make a difference. This experience had a profound impact on my life, and I hope CHM can continue to be a place where young people can express themselves and inspire others for years to come. What follows is a description of the internship experience from the interns themselves.

@CHM blog contributors. Left to right: Bryan Polk, Leena Mathur, Shiva Balachander, Anushree Ari, and Ishani Desai.

Returning to CHM’s internship program for a second summer—this time as a mentor—my role was to use my previous experience to help this year’s interns build their confidence and content proficiency to engage and enhance visitor experience at the Museum.

To get ourselves acquainted with the Museum and computer history, we went on guided tours, which gave us ideas of how to interact with visitors, and used CHM’s website to understand the relevance of the artifacts and the functions of the machines in Revolution.

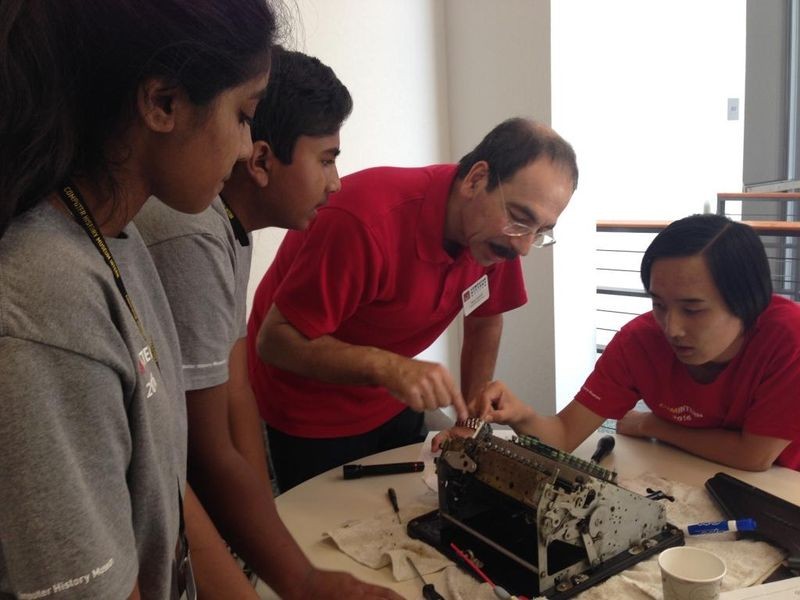

2016 interns with docent Marc Verdiell.

CHM staff also helped us familiarize ourselves with the Museum, building our confidence in our artifact, history, and museum knowledge. This helped us understand the different roles that are necessary to run the institution and how CHM staff interacts to make the Museum function every day. Guest speakers, such as Al Alcorn, creator of the game Pong, told us incredible stories about their experiences working in the computing industry that inspired us and fueled our passion for technology. These speakers inspired us, new interns and experienced mentors alike, by sharing life lessons about persevering and believing in possibilities.

Teamwork was another thread throughout this internship. Interns frequently presented and shared their research with the group, which in turn led to having more content for each intern to explain to visitors, as well as more confidence in the subject matter. These interactions helped strengthen bonds between the interns and created genuine friendships among us.

As a mentor, I had to find a way to encourage our new interns to answer questions in a group environment, even though most of them did not know each other and were still acclimating to the Museum. This experience taught me how to motivate a group to be outgoing and social. After working with the interns for a few weeks, they started becoming more confident and open to talking to one another. The new interns were ready to take on their roles as Exploration Station managers and Gallery Interpreters!

Video: Interns working on restoration project with docent Marc Verdiell...

Leena Mathur with her favorite artifact, Shakey.

Artifacts make history real. For some, they bring back memories. For others, they provide a deeper understanding of the past. Artifacts serve as bridges, connecting people who relate to them. The artifacts in the Computer History Museum have more than a technical significance. Each object, from the abacus to the autonomous car, has a social impact that directly, or indirectly, affects our lives.

We interns researched the technical dimension and the human story behind the artifacts in our areas of interest. Apart from expanding our own understanding of the history of innovation, our goal this summer was to engage with Museum visitors of all ages and backgrounds and further their appreciation of computer history. We attempted to get visitors to make personal connections to the artifacts in the galleries. Since I am interested in computer science, engineering, and robotics, I chose to research the objects in Gallery 12 (Digital Logic) and Gallery 13 (Artificial Intelligence and Robotics).

I interacted with hundreds of visitors in Gallery 12 over the summer. Visitors ranged from young kids to industry veterans! While discussing Moore’s Law and the exponential growth of computing power in integrated circuits, I came across an intergenerational family group. After I shared my comparatively limited knowledge of the exhibit with the two kids, their grandfather excitedly shared his stories about the early days of microprocessors and integrated circuits. He had worked at Fairchild Semiconductor in the 1960s! He enthusiastically took over and guided us around the gallery, describing the chip development process and explaining the exponential growth in computing power made possible by the development of semiconductor technology.

In Gallery 13, I enjoyed observing visitors relate to the robot Shakey, my favorite artifact. Shakey, developed at the Stanford Research Institute in the late 1960s, was the first mobile robot designed to reason about its actions, pioneering several AI techniques. Some younger kids related to Shakey by comparing it to Pixar’s Wall-E. Student groups from local tech-camps came to the Museum, looking for Shakey. Most people wanted to know why this robot was called Shakey, expecting some deeper reason other than the fact that it shook a lot. There was no other reason. It shook a lot!

The Exploration Station in the Museum’s lobby was another area that we interns staffed. This station allowed visitors an opportunity to connect with artifacts in a hands-on way. Consistently across generations, the one artifact that drew the most attention was the IBM 026 keypunch. Many of the older visitors excitedly discussed their days using punched cards and all their trials and tribulations with machine breakdowns and dropped card-decks. Visitors across all age groups seized the opportunity to punch a card. During one of my shifts, a kid patiently stood in line three times to punch additional cards to take home for friends! Older visitors often pointed out floppy disks and game cartridges to their younger children. It was fun to hear parents talking about how long they had to wait for programs to load on their computers. One father nostalgically described a floppy disk to his daughters, who looked curiously at the foreign object and snapped pictures of it with their iPhones.

Shiven Gupta and Somya Bhatia stationed at the Exploration Station in CHM lobby.

The Computer History Museum, with the largest collection of computing artifacts in the world, truly encourages intergenerational learning and inspires its visitors to relate to computer history. As an intern, I enjoyed facilitating and observing the interactions.