With sadness, we say goodbye to computer pioneer and 2022 CHM Fellow Donald L. Bitzer.

Don Bitzer. Credit: National Inventors Hall of Fame

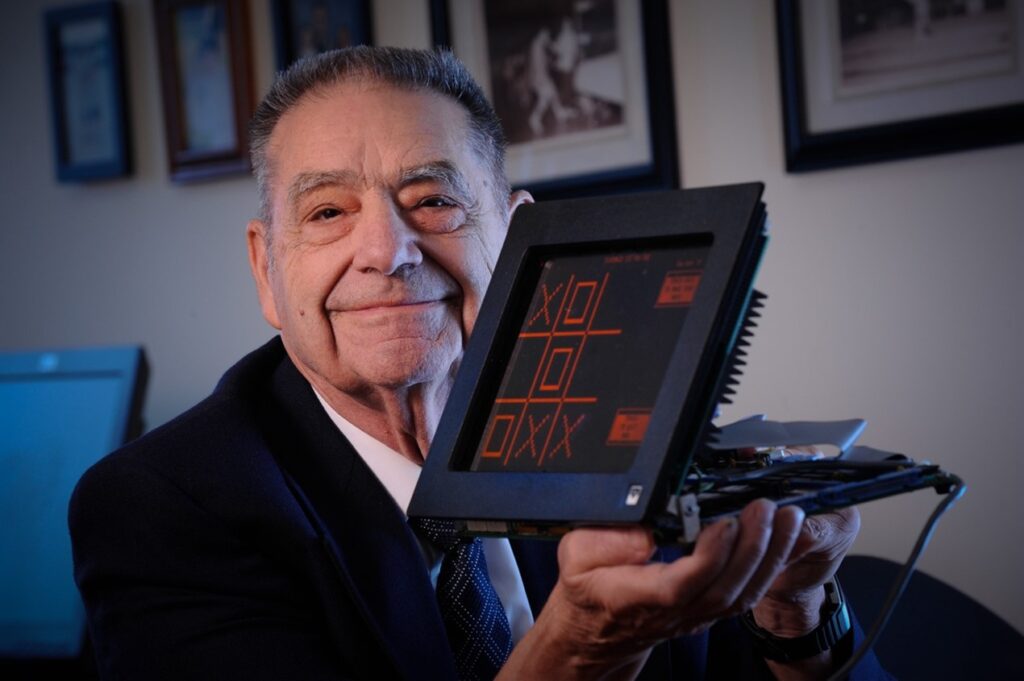

Bitzer was born January 1, 1934, and was an American electrical engineer and computer scientist. He was co-inventor of the flat-panel plasma display and the "father of PLATO,” the world’s earliest time-shared, computer-based education system and home to one of the world’s most pioneering online communities.

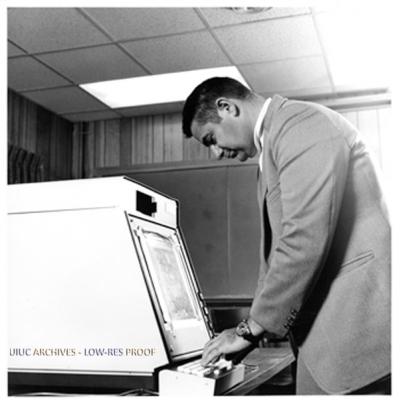

Bitzer studied electrical engineering at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC), obtaining a PhD in 1960. Following graduation, he joined the UIUC faculty, where he learned of efforts to bring lessons to students over a closed-circuit television network. While a committee of engineers, psychologists, and educators were unable to agree on a single solution at the time, Bitzer wrote up a proposal within a week, got it approved, and immediately started developing his PLATO system for the university’s groundbreaking ILLIAC I computer—the first electronic digital stored program computer built by a university. (PLATO stands for Programmed Logic for Automated Teaching Operations).

University of Illinois ILLIAC I computer, ca. 1952. Credit: University of Illinois

To expand multimedia for courses, later PLATO terminals incorporated microfilm projector that could combine detailed images with computer text on the screen, and some used an attached magnetic audio disk for language and music instruction. To make things easier on the eyes for students sitting in front of computer terminals for many hours at a time, in 1964 Bitzer, with colleague Gene Slottow and graduate student Robert Wilson, invented the flat panel display: plasma screens do not flicker and their clever design also saved memory in the computer by having the display itself store data.

By the early 1980s, PLATO supported thousands of student terminals worldwide, running on multiple different mainframe computers. Many modern concepts in multi-user computing were developed for or matured under PLATO, including forums, message boards, online testing, email, chat rooms, instant messaging, remote screen sharing, multimedia, and multiplayer video games.

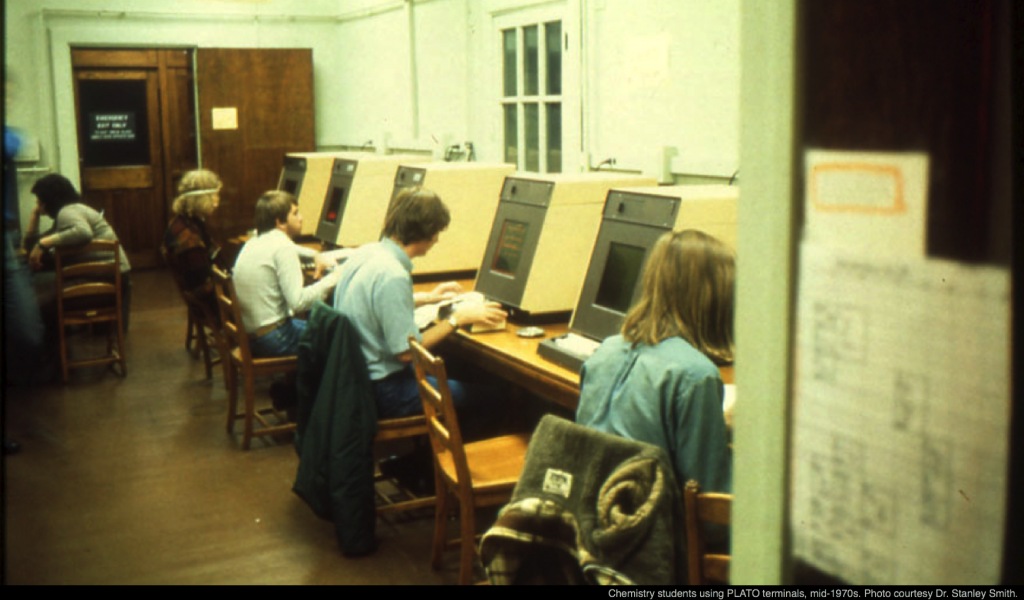

University of Illinois chemistry students using PLATO terminals, ca. 1975. Credit: Dr Stanley Smith.

In 1989, Bitzer left Illinois to join the faculty of North Carolina State University, where he was most recently Distinguished University Research Professor of Computer Science. Bitzer was also a member of the National Academy of Engineering, the National Inventors Hall of Fame, an IEEE Fellow, and a 2002 Emmy Award winner for his co-invention of the flat-panel plasma display.

Bitzer, with the flat-panel display which he co-invented in 1964 with colleague Gene Slottow and graduate student Robert Wilson.

When networks like the internet were still a research lab curiosity, Don Bitzer's multiuser PLATO system served as a dress rehearsal for what we do on those networks today—learn, teach, collaborate, chat, mail, play games, argue, and more. PLATO's courseware language and touchscreen, multimedia terminals previewed features of decades hence. Bitzer's PLATO system was a postcard from the future of online communities, and its example would help make that future real.

Bitzer at PLATO terminal. Credit: University of Illinois Archives, ID 0003303

Dear, Brian, The Friendly Orange Glow: The Untold Story of the PLATO System and the Dawn of Cyberculture, Pantheon, 2017.

Kaiser, Cameron, "PLATO: How an educational computer system from the ’60s shaped the future," Arstechnica, https://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2023/03/plato-how-an-educational-computer-system-from-the-60s-shaped-the-future/

PLATO @50: A Culture of Innovation, Six-Part Series, Computer History Museum, June 3, 2010.

Oral History of Don Bitzer, Computer History Museum, July 27, 2022.

Computer History Museum PLATO objects.