On October 19, 2021, CHM introduced the inaugural Patrick J. McGovern Tech for Humanity Prize Changemakers to a virtual audience to share how they’re shaping a better future for us all with their passion for solving global challenges.

The Prize embodies CHM commitment to tech for good and honors Patrick J. McGovern’s spirit of optimism and his belief that technology can be a positive force. Trustee and Chair of the Board of the Patrick J. McGovern Foundation Patrick McGovern spoke about his father as a changemaker who helped to define an entire era of technology advancement with groundbreaking publications that have provided key data and analysis about the tech industry for decades.

Patrick J. McGovern believed that people could change the world, and from a field of talented applicants the tremendous potential of their innovations made Mercy Nyamewaa Asiedu and Michael Bernstein stand out. Read on and you'll understand why.

Raised in Ghana, Mercy received a scholarship from the Zawadi Africa Education Fund to study in the US at the University of Rochester, where she majored in biomedical engineering and discovered her passion for using tech to solve global health problems. She realized that middle and lower income nations often miss out on the benefits of healthcare technologies created in more developed nations. Even when they are transplanted, issues around maintenance, power, internet connection, and human resources often means they end up in a rubbish heap rather than helping people.

Discarded medical technology in Africa.

To address this problem, Mercy determined that she would work to develop tech with developing countries in mind from the start. She earned a PhD in biomedical engineering at Duke University with a focus on global health and then accepted a Schmidt postdoctoral fellowship at MIT... and she cofounded two health equity startups. Her Changemaker award advances their work.

Motivated by personal losses, GAPhealth bridges the gap between patients and clinics, providing smarter healthcare for chronic disease management and actionable, representative data to understand what’s really going on and predict trends.

Mercy explains how GAPhealth can help patients manage chronic disease.

Mercy’s other startup, the Calla Health Foundation, seeks to reimagine gynecology, including updating a basic diagnostic tool—the speculum—that hasn’t seen any change in 150 years (!!!) and democratizing access to cervical cancer diagnosis. Every year, there are 500,000 new cases of the disease, which claims 55% of patients. Over 85% of deaths from cervical cancer occur in lower or middle income countries due to lack of screening, but cervical cancer is slow growing and extremely preventable and treatable if found early.

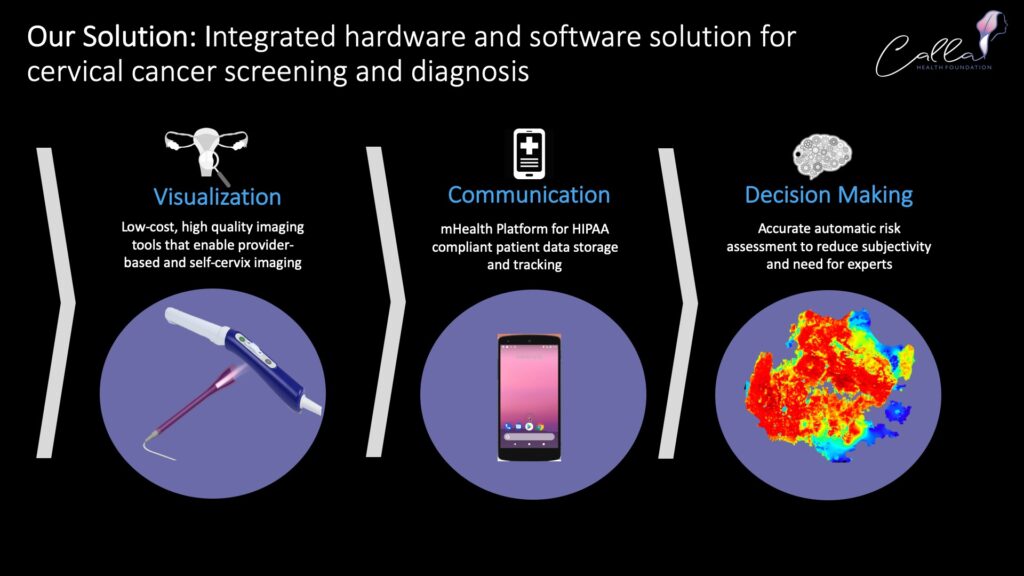

Calla Health has developed low-cost tools for early cervical cancer screening and diagnosis: high quality imaging tools for providers and self-imaging tools for patients with a mobile app for data storage and tracking and decision-making algorithms that provide risk assessment. The portable pocket colposcope received FDA approval and works as well as a $20,000 device. Patients can use the callascope themselves, in lieu of the speculum, which is invasive and can be painful. Both devices have been tested in ten countries, receiving positive feedback from women and diagnoses with above 80% accuracy, better than expert providers.

Calla Health technologies.

Changemaker prize money allows Mercy and her and her team to improve and generalize the model so it works seamlessly across different clinics, realizing her vision of healthcare that democratizes accessibility and provides data for machine learning that is truly representative of the diverse populations she aims to serve.

Changemaker Michael Bernstein is an associate professor of computer science at Stanford University, where he’s a member of the human computer interaction group. He earned a BS in symbolic systems from Standord and an MS and PhD in computer science from MIT. His research considers how artificial intelligence (AI) is embedded in social systems, where sometimes they work for and sometimes against people. AIs themselves are influencing platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Wikipedia, and even Zoom, and they change the way we interact with each other.

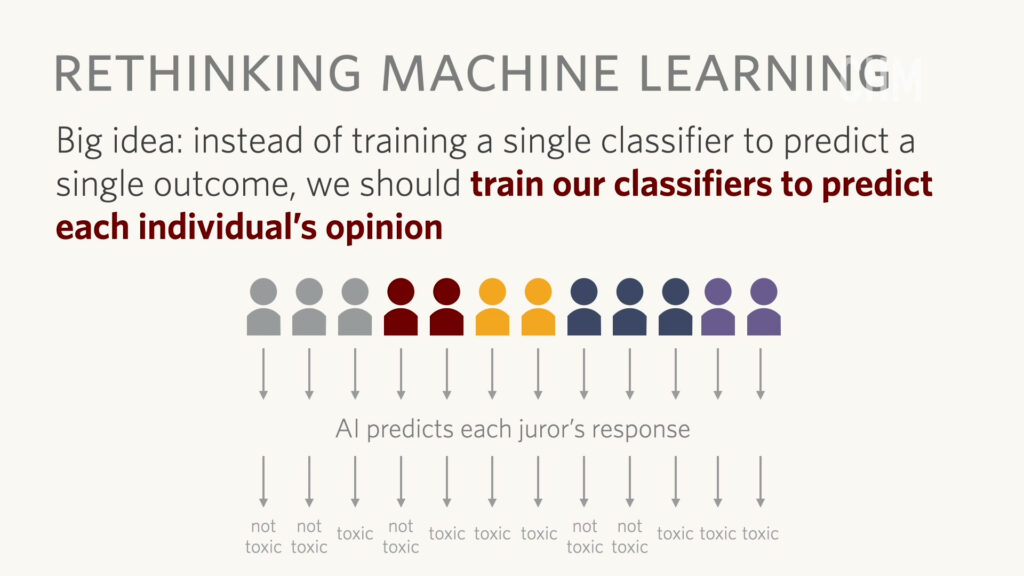

Michael was inspired to start his project by asking questions about who is benefitting from and who is being harmed by AI and wondering whose labels we are using to train them. Machine learning systems for AI are built and developed through majority vote, which works well for tasks like identifying the difference between cats and dogs, but for social media applications, things are more complex. Majority vote might silence critical minority opinions on what is toxic content, for example. It is here that Michael hopes to make a difference with a new model for machine learning based on a jury metaphor.

Michael explains how the jury model helps solve the problem of bias.

Michael believes that by making the jury used for a machine learning model public, there can be an opportunity for participatory democracy and transparent decisions. Communities can articulate their values in selecting the jury composition and dissent can be visualized and outcomes changed depending on who is on the jury.

The jury model takes into account multiple points of view.

To see if it works in practice, Michael’s team recruited social media moderators to test it. When people were permitted to have a choice of the datasets they used for moderation decisions, they shifted from 74% white to 25% on average. That changed about 14% of classifications, and the ones most likely to flip were the most divisive comments, which are also the ones people care about most. In sum, the researchers saw a large increase in the diversity of voices guiding AI decisions and that resulted in different outcomes.

Now Michael and his team are working on a website where people can explore jury learning and they want to open source the code soon so companies can start using it. As technology mediates more and more of our human interactions, we can change how well those interactions if we design it better, says Michael. What would that look like? Gig work platforms that are more prosocial, the ability to conduct hundreds of experiments at the same time, the power to coordinate inputs from thousands of people, or help online workers organize. We can work to create more democratic and participatory governance online by building the infrastructure to support these models. Jury learning is a great start.

Following the Changemaker presentations, tech media pioneer, health advocate, and selection committee member Esther Dyson asked Mercy particular questions, Pixar cofounder and selection committee member Ed Catmull offered congratulations to Michael, and the chair of the prize selection committee, futurist Paul Saffo, posed additional questions to Michael and Mercy.

Mercy described how it’s necessary for her to work with local clinics in order to access patients around the world to test and use her new technologies. She also finds them through social media, using WhatsApp and Instagram to spread awareness about her work. She described the challenges of gathering data for research in Africa.

Michael discussed how explicitness about who is in the jury means that we are putting our values out there. We’re asking less about how an AI model works and more about where (and who) it is coming from. That’s an important change.

Paul Saffo asked the changemakers how they respond to skeptics during a time when some people doubt science and others find aspects of their work scary, like AI (Michael) and aggregating private patient data (Mercy). Mercy says mistrust in healthcare is nothing new. Michael applauds the impulse to question.

Mercy and Michael discuss the role of trust in their projects.

Both changemakers believe strongly that the people who are impacted by the technology they create must be given a voice. Communities that are often overlooked must be intentionally sought out and their participation actively pursued.

For tech to truly move humanity forward, we must include all of humanity.

With support from the Patrick J. McGovern Foundation, the Patrick J. McGovern Tech for Humanity Prize includes $100,000 in awards to advance Changemaker projects and an optional residency at the Museum. Learn more about the prize.

Tech For Humanity Changemakers | CHM Live, October 19, 2021