The modern internet spans the whole world. Who made what parts of it?

Who really invented the Internet? I was fascinated by the recent kerfuffle over this question, which started with Gordon Crovitz’s July article, Gordon Crovitz: Who Really Invented the Internet? in the Wall Street Journal. The catch is that even if you could dispel the political agendas of the folks writing (Crovitz wanted to show that private trumps public), or erase the sad fact that only a few people know enough of this history to discuss it usefully, you would be left with a trick question – because the word “Internet” means several different things today. You can find all the main meanings within Crovitz’s article and the various rebuttals to it. The result is a thick stew of confusion. Yet if we take the different senses of “Internet” one at a time, we can find a certain order. Let’s start with the broadest one, where “Internet” has become a generic term for the entire online world – from the wires and switches that lay its foundations, to a cat video playing on a child’s iPad.

Just as Xerox became a verb for copying, “Internet” has become the popular generic term for anything to do with computer networks. This is partly because there was no well-established term when most people first went online in the ‘90s (or at least none shorter than “information superhighway”). So like a newborn duckling who forms a maternal bond with the first thing it sees, we collectively imprinted on the name of the best-known component of the online world. Despite misgivings, I use the word in this sense for the CHM Internet History Program. Who invented the online world? Many people. It’s like asking who invented Rock and Roll: Elvis, or Little Richard, or Les Paul by perfecting electric guitar techniques, or the many DJs who took a chance and played the new music to initially unreceptive audiences. All count. Of course, like certain guitar techniques, some of the online world’s components do have identifiable inventors. Take the World Wide Web. This roughly 20-year-old system is the familiar face of the online realm for most people; it includes the browser you’re likely reading this on, as well as Web addresses like www.computerhistory.org. The Web is a user-friendly layer on top of the largely invisible plumbing that makes networks go. The Web’s main inventor was Tim Berners-Lee, though with major help from project partner Robert Cailliau and assistants including Jean-François Groff. But the Web beat out or absorbed a number of other online systems that did roughly similar things, from CompuServe to Hyper-G to Gopher. So Berners-Lee et al invented the winning entry–but not the general category. You may ask: who invented online systems in general? That’s a story that goes back at least to the 1960s and has its own cast of inventors, from the creators of timesharing systems to hypertext visionaries Doug Engelbart and Ted Nelson. Online systems even have roots in pre-computer efforts to navigate knowledge with machines, like Paul Otlet’s Mundaneum and Vannever Bush’s Memex concept. But this story of a general category, and then a single winner beating out rivals within it, is a repeating theme. We’ll find it again as we move further down from the familiar user layers you see and click on (like the Web and other online systems) to the lower, “plumbing” layers of the online world like the Internet in its original senses.

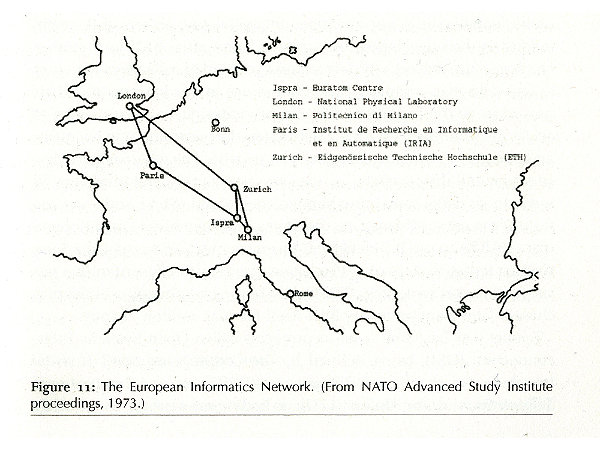

This is the original 1970s meaning of the word. A little background is required… as soon as once standalone computers started getting hooked together into networks around 1970, there was a problem. Those networks couldn’t talk to each other. They were like little islands. There was the well-known ARPANET, and also the NPL network in the UK, and soon several others, and they were all isolated. The solution was to create standards that could translate data between them and tie them into networks of networks. This process is called “internetworking” or “internetting,” and the result is called an “internet.” Who invented internetting? Many people, and most knew each other as members of the small but global networking community of the time. The first experimental internetting connection to get off the ground may have been the European Informatics Network in ’73, which among others connected Louis Pouzin’s Cyclades network in France and Donald Davies’ NPL Mark I network in the UK. But at nearly the same time Xerox PARC began experimenting in-house with the proprietary internetting protocol called PUP (PARC Universal Packet).

By the mid 1970s the European Informatics Network had set up internetworking between England’s NPL network and France’s CYCLADES network, with nodes in Italy and Switzerland. © NATO Advanced Study Institute

So yes, Bob Metcalfe of Ethernet and Xerox PARC fame really did help pioneer internetting, one of a few historical facts the Crovitz article gets right—and which many of the rebuttal authors don’t seem to realize. But, and these are large “buts,” PUP was a corporate secret at the time and would only partially influence the later Internet protocols we now use and love. Instead, Metcalfe and his colleague David Boggs got known for Ethernet, which like other local area networking standards (LANs) is a somewhat separate kind of animal, optimized to connect machines together locally within a building or complex. Also in 1973, Vint Cerf and Bob Kahn of ARPA, the agency which had funded the ARPANET, began to think about an internetting protocol of their own. The result was our next definition of “Internet.”

The van where the Internet was born, filled with high-tech equipment, was used for a November 1977 test interconnecting three dissimilar networks with the eventual Internet protocol, TCP/IP. The van was built for fundamental research in packet-switched radio networks, the basis of today’s mobile data services.

History is written by the victors. Thus, what we call “the” Internet is quite simply the internetting standard that beat out its rivals. Who wrote it? Vint Cerf and Bob Kahn of ARPA, while drawing on heavy contributions from others in the internetting community mentioned above. They started thinking about it in 1973, and the first field trials came in 1976 and 1977. But the Internet standard we use today didn’t emerge victorious in the 1970s. Back then, it was mostly a proposed upgrade to several of ARPA’s experimental networks. In fact, for the next ten years the official favorites were a new generation of internetting standards, especially the internationally backed OSI. The Internet’s eventual victory around 1990 was somewhat of a surprise, helped by a grassroots developer community and backing from the U.S. government (including Senator Al Gore).

So which is better? There are many valid questions about the merits of private vs. public enterprise. But I believe the birth of computer networking, along with several aspects of computing, are some of the worst possible examples on which to build a political argument. Because they were exceptional, in both senses. For every Xerox PARC, which in a few short years roughed out many of the foundations of modern computing, there are dozens of corporate research labs with utterly pedestrian output. For every ARPA in its golden age, there are scads of government research agencies that fail to back a single project half as game-changing as the ARPANET or the Internet, much less several. The successful efforts from ARPA, SRI, and PARC had much to do with the time—the dawn of widespread computing, when much was open and yet to be designed—and with the people involved. These latter were some of the most talented and visionary technical people of any generation. They were a close-knit group, and many of them flitted frequently between government, industry, and academia like bees in a flowerbed, blurring any meaningful distinction. For instance, Bob Taylor ran ARPA’s computing division during the creation of the ARPANET. He then moved to Xerox PARC and promptly hired dozens of the folks he had recently been funding in academia, industry, and consulting firms; including Bob Metcalfe of Ethernet fame. The result was the basis for the modern PC office, by 1973. Perhaps there’s a lesson there, that these researchers could do things in a company they couldn’t in government funded research. Or vice versa. But there haven’t been enough PARCs and ARPAs to do much meaningful comparison. In my view, many top researchers effectively work for another sector entirely, one that is not quite industry, or government, or even academia, though it may be funded by all of them. This fourth sector exists in the spaces between the others: in conferences and industry alliances, in standards bodies, and in firms like SRI and BBN that do lots of government-funded research. Much of the online world – including the Internet in whatever sense you personally prefer – got made there.