Last week, on June 22, 2020, Apple announced that it will be transitioning future Mac computers away from using Intel microprocessors to chips based on its own designs, using the ARM architecture already being used on its iPhones and iPads. This isn’t the first time Apple has switched out the chips used in the Mac. In 2005, Steve Jobs announced Apple was moving Macs away from PowerPC processors to Intel. And in 1994, Apple shipped its first Macs with PowerPC chips, replacing the Motorola 68000 series of chips used since the original 1984 Macintosh.

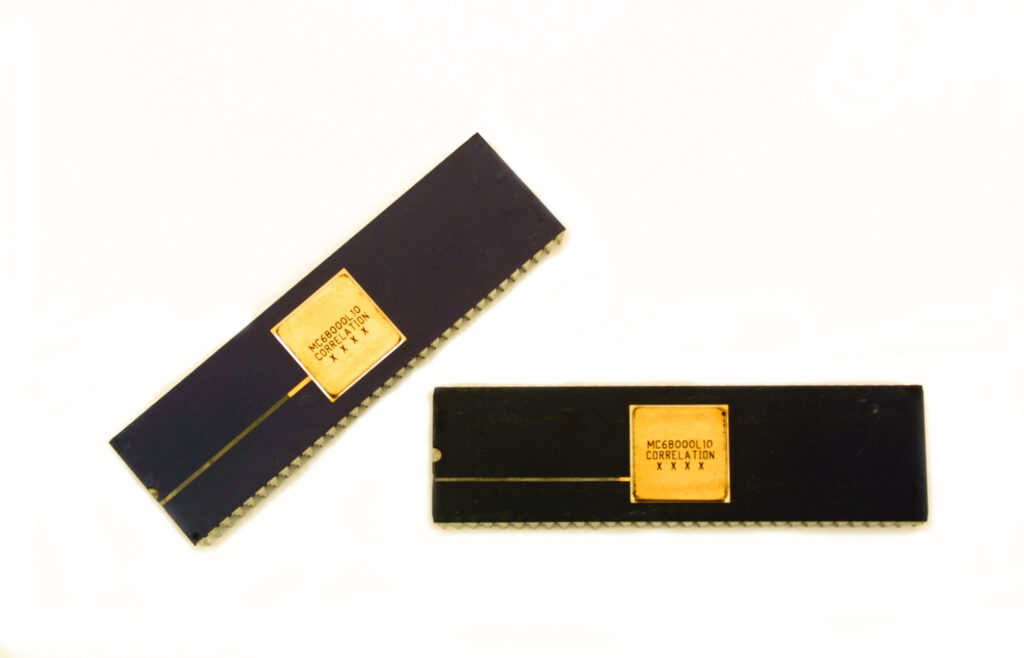

Motorola 68000 chips used in the original 1984 Macintosh, as well as the Plus, SE, Portable, and Classic. Collection of the Computer History Museum, X1307.97, 102662157, and X224.83A.

Apple is one of only a few computer companies to successfully move its entire platform away from one processor onto another. This is typically very difficult. Software written for one type of processor generally doesn’t run on another. This is because a particular processor family defines what is called an “instruction set architecture,” or ISA. Software written for that particular processor takes the form of machine code, or instructions, specific to that processor’s ISA. This is one of several reasons why Macs and PCs couldn’t easily run software written for the other, or why apps written for your iPhone don’t currently run on your Mac. This creates a problem for computer platforms that have a large installed base of software. Users aren’t going to want to buy new computers from your company if you don’t give them a way to run the software they already have.

The solution that Apple used each time it switched from one processor to another was to use emulation. This is a program that translates, in real time, instructions written in one ISA to a different one. In other words, it translates the software you already have into native machine code for the new computer you just bought. This maintains backward compatibility for your old software while allowing new computers from the company to continue to get faster with processors using the new architecture. The downside is that emulated software runs slower than it would on its original processor.

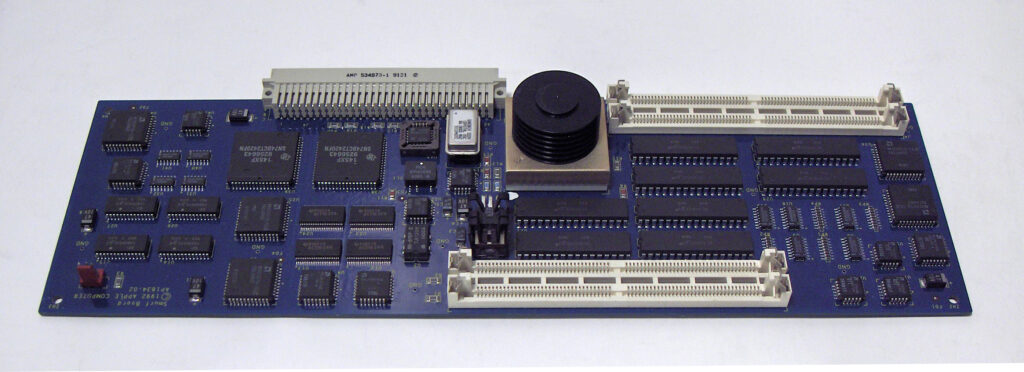

1992 prototype Apple “Smurf” card. Boards like this were used to test the first PowerPC chips with Davidian’s 68000 emulator. Collection of the Computer History Museum, 102674143.

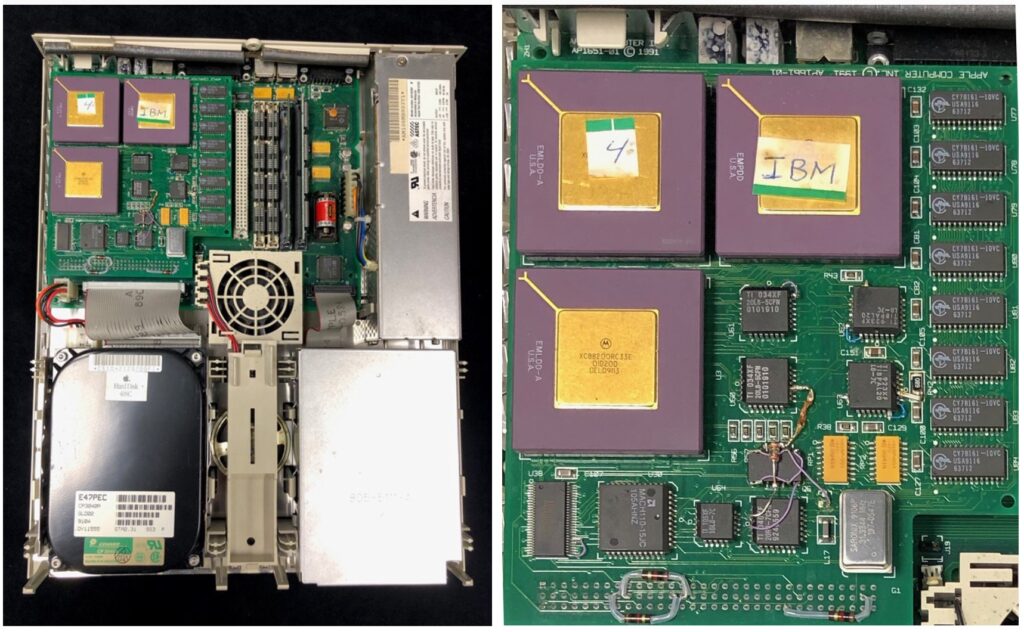

Apple did this the very first time in the early 1990s, with the move from Motorola 68000 (a.k.a. 68K) to PowerPC. Motorola’s 68K chips were losing steam, and in order to keep up with IBM PC compatibles running Intel processors, Apple got together with Motorola and IBM to define a new processor architecture, the PowerPC. In order to make this move while still supporting all of the Mac’s existing software, including its operating system, Apple needed to create an emulator for 68K instructors that would run on the PowerPC. This was a multi-year project, which was started by engineer Gary Davidian at Apple in the middle of 1990. Before the PowerPC collaboration even began, several internal projects at Apple were already looking at porting the Mac’s operating system to run on alternate processors. Davidian explored using the AMD 29000 processor that was used in one of the Mac’s high-performance graphics cards. By early 1991, Davidian had written an emulator that ran on the Motorola 88000 processor, because of managerial pressure to maintain the existing Motorola supplier relationship. This processor was on a card that plugged into a normal Mac IIx (see Figure 2). Davidian’s emulator served as a proof of concept that emulation of 68K code could be done without too big of a hit in software speed. This convinced managers at Apple that emulation was a workable solution for users. The next step was to produce a prototype computer, in the form of a Macintosh LC case with a Motorola 88100 CPU inside. Davidian’s group had finished this prototype by middle of 1991.

Left: Prototype with a Motorola 88100 processor inside a Macintosh LC case. Note the Motorola chips in the top left corner. Right: Detail of Motorola chips. Courtesy Gary Davidian.

In October 1991, Apple announced the PowerPC alliance with IBM and Motorola, and work began to shift Davidian’s emulator over to the PowerPC architecture. New prototype plug-in boards and then full machines were built with the new chip, whose bugs were still being worked out. It took several more years, until 1994, for the first Macs with PowerPC processors, the Power Macintosh 6100, 7100, and 8100, to be released to customers. The PowerPC would be the Mac’s CPU until 2006, when Apple replaced it with Intel’s processors.

CHM recorded a set of oral history interviews with Gary Davidian on February 5, and March 15, 2019. In particular, Davidian discusses his work on the 68K emulator in Part 2 of the oral history.

Oral History of Gary Davidian, Part 1, interviewed by Hansen Hsu on February 5 2019, 2018 in Mountain View, CA, X8931.2019 © Computer History Museum. Transcript.

Oral History of Gary Davidian, Part 2, interviewed by Hansen Hsu on March 15 2019, 2018 in Mountain View, CA, X8931.2019 © Computer History Museum. Transcript.

![]()