The garage has long played host to the creative genius of aspiring technology entrepreneurs here in the good ole Valley de Silicon. Take, for example, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak, who built the first Apple computers within the confines of Jobs’ parents’ Los Altos garage. There’s the famous HP duo, Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard, who began their company in 1939 out of Packard’s garage in Palo Alto. And then there’s Onslow H. “Rudy” Rudolph (1929–2008), who in 1959 started his own business in the family garage before being joined by his partner in crime, Ken Sletten, in 1962. Rudolph and Sletten are part of the garage start-up brotherhood, but they weren’t building computers. No. They were building a company for building companies, and would go on to construct multiple buildings, including some of the first corporate campuses, for the very same Silicon Valley companies that started-up in a garage.

On February 11, 2013, Duane Wadsworth of the Computer History Museum’s Semiconductor Special Interest Group had the good fortune to interview Kenneth G. Sletten, co-founder of Rudolph and Sletten, the Valley’s go-to general contractor for more than fifty years—better known as “the contractor that built Silicon Valley.”

The Museum’s oral histories collection is filled with the stories of inventors, pioneers, go-getters, entrepreneurs, and risk-takers that together produce a campfire-like telling of the computer revolution from the legends themselves. While many of our oral histories chronicle the triumphs and failures of various products, people, and companies, the Museum also prides itself on offering new perspectives in computer history. Ken’s oral history is a prime example of this effort given the fact that he is not a computer engineer, but a civil engineer whose contributions to the making of Silicon Valley are as equally innovative and significant as any technologist. Inspired and intrigued, I decided to dive in deeper.

As I enthusiastically set out to explore the “building-scape” of Silicon Valley, I began scouring the web for images of early buildings and construction sites from the long list of companies Ken references in his oral history. Despite some of my more creative Google searches, I was unsatisfied with the results. Given the amount of company turnovers and takeovers, along with having no real frame of reference with the exception of Ken’s verbal descriptions, and given the fact that most Silicon Valley history isn’t about the building but what’s being manufactured inside of it, it was nearly impossible to decipher whether an image contained an original building. With the art historian in me rearing her persistent head, I thought: a story about buildings has to have pictures! That’s when I decided to place a call to the source.

Ken invited me to his office at Sunnyvale’s Moffett Towers, where he currently serves as managing director of the advisory board for Level 10 Construction—the general contractor spearheading all building efforts for Facebook’s new 433,000-square-foot west campus, designed by famed postmodern architect, Frank Gehry. When I arrived, I was warmly greeted with a hug from Carolyn, Ken’s assistant since 1990, and friendly handshakes from former Rudolph and Sletten executive, Dick Blach, and of course, from Ken himself. Ken was generous enough to dig out from storage and supply me with over twenty binders and folders filled with old slides and photographs from some of Silicon Valley’s earliest buildings including Fairchild, National Semiconductor Corporation, Digital Equipment Corporation’s west coast headquarters, Xerox PARC, multiple buildings for Hewlett Packard, Lockheed, and Apple. As I carefully turned the plastic inserts, stopping every so often to select a slide and hold it up to the overhead lights, Ken and Dick rattled off countless stories, names, and dates with the same ease and fondness as a mother recounts the accomplishments of her children. I frantically jotted down as many notes as I could while trying to keep my head about me as I was in the presence of, what I like to call, “Silicon Valley awesomeness.”

What follows are my notes from this encounter, video clips and quotes from Ken’s oral history, and images from the collection of binders and folders that he loaned me.

National Semiconductor Corporation, January 1, 1972 Architect: Dennis A. Kobaza & Associates Photographer: Marvin Wax © R&S limited; Courtesy of Kenneth G. Sletten

HP 15 Renovations Porter Drive, Palo Alto, 1973 Architect: ENR Photographer: Marvin Wax © R&S limited; Courtesy of Kenneth G. Sletten

HP Building 42 © R&S limited; Courtesy of Kenneth G. Sletten

Digital Equipment Corporation (west coast headquarters), 80,000 square feet, 2525 Augustine Drive, Santa Clara, 1970s Architect: Gensler & Associates Photographer: Marvin Wax © R&S limited; Courtesy of Kenneth G. Sletten

Xerox Corporation, 1980s, © R&S limited; Courtesy of Kenneth G. Sletten

Hewlett Packard Building R3, Electronics Manufacturing Building, 8000 Foothills Boulevard, Roseville, California. © R&S limited; Courtesy of Kenneth G. Sletten

Hewlett Packard Buildings 52/53, Steven’s Creek and Lawrence Expressway, Santa Clara Architect: Clark, Stromquist & Sandstrom Photograper: Martin Wax © R&S limited; Courtesy of Kenneth G. Sletten

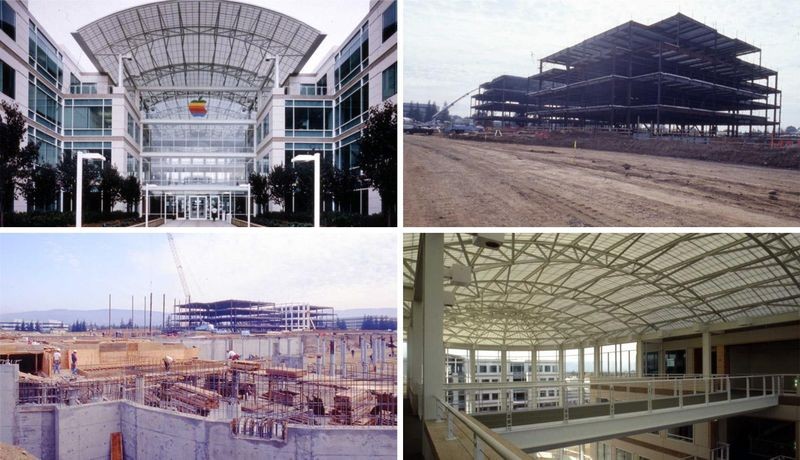

Apple Research and Development Campus, 856,000 square feet, 1993 Architect: Hellmuth, Obata + Kassabuam, Inc; BAR Architects(interior) and Gensler Architecture and Design (interior) Photographer: Marvin Wax © R&S limited; Courtesy of Kenneth G. Sletten

Kenneth G. Sletten (left) with business partner Onslow H. “Rudy” Rudolph

Kenneth G. Sletten was born in Helena, Montana, before moving with his family across state to Billings at the age of 5. During his childhood and up through high school, he recalls doing odd jobs that always revolved around some aspect of construction, though he notes in his oral history that they were not necessarily the most glamorous of jobs. Sletten remembers digging ditches for the city water company and working in a warehouse that distributed construction supplies. He also worked for the Bureau of Reclamation in Buffalo, Wyoming as a surveyor during his last summer of high school. He says, “I knew that I liked to be outside, and I liked mathematics, too, as a matter of fact, so it [construction] seemed right for me and I knew it right from the beginning.”

Sletten attended the University of Colorado on a Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps (NROTC) scholarship, where he received a Bachelor of Science degree in civil engineering. In his sophomore year at the University of Colorado, he transferred from the Navy to the Marine Corps. As a Marine, Sletten served in Korea and also made his first trip to the West Coast, where he recalls being stationed in Oceanside, California. After nearly a year spent recovering from an injury he sustained in Korea, Sletten signed up for Stanford Business School in 1954 at the urging of a close friend. His first job after graduating from Stanford in 1956 was with the Belmont, California, construction company, Williams and Burrows. This is also where Ken first met Rudy.

Onslow H. “Rudy” Rudolph was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He learned the carpentry trade from his father and uncle, who learned it from their father, who learned it from his father before him. In 1946, Rudy, who at the age of 23 had already been a second lieutenant in World War II, moved to San Jose to attend San Jose State University where he earned a Bachelor of Science degree in engineering. Upon graduating in 1951, he worked for several companies throughout California, including Williams and Burrows, before setting out to create a company of his own.

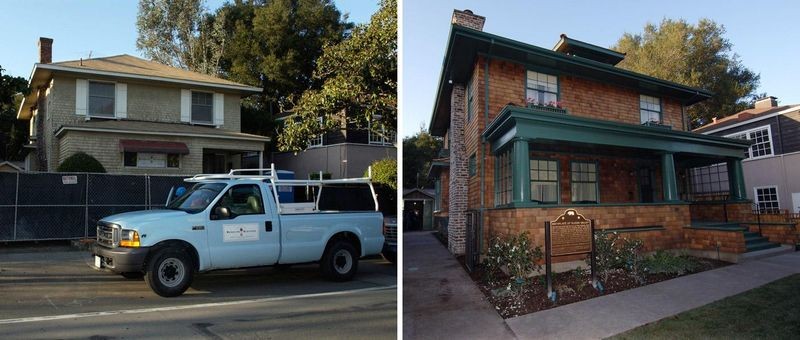

After joining forces in 1962, Rudolph and Sletten landed one of their first Silicon Valley clients, child superstar Shirley Temple Black. Both recall this memory with fondness, albeit somewhat differently. Rumor has it that the iconic sky blue paint of Rudolph and Sletten’s truck fleet is the result of this early job. In an interview Rudy explains, “One of our first clients was Shirley Temple Black. Mrs. Black requested that the structure be painted bright blue; and the Rudolph and Sletten trucks bear the identical shade, a reminder of our roots.” With my curiosity piqued, I decided to ask Ken about this story to see if I could unearth more details. He is not wholly convinced that there was ever any connection between the color of their trucks and Shirley Temple Black’s pool house, but perhaps may have been a tale-turned-fact by his late partner’s sense of humor. What is true is that baby blue is Ken’s favorite color, which is the primary reason they had that particular color on hand for the job. I should note that upon hearing my conversation with Ken, Dick sides with Rudy.

Having lived and worked in the Bay Area, Rudolph and Sletten were drawn to the exciting events taking place in Silicon Valley. Like many start-up companies, they were hard workers, believed in their product, and had the foresight to recognize that tech was going to be big. Ken recalls that many established general contractors in the Bay Area were nervous about high-tech and what was going on in the Valley. It was a gray area and “a place where you could get in trouble.” And with that, Rudy and Ken jumped in without looking back.

Sletten recalls that when he and Rudy first began landing clients, such as Fairchild and Lockheed, they were a bit of an anomaly amongst other general contractors in that they were engineers as well as businessmen. As Ken puts it, “We presented ourselves as businessmen and not just contractors—businessmen-engineers and not just contractors—and we wore suit[s] and ties to talk to our clients, and they’d treat us with a little more respect, I think, because of that.” But more than that, Rudy and Ken built their reputation by being reliable, doing good work, by staying on schedule, and keeping within budget. Ken says, “We just learned by doing, and being sure that we understood exactly what went into that job, and as engineers, that’s the way we think, anyhow.”

Video: Sletten recalls his and Rudy’s early fascination with Silicon Valley, along with some of their first clients including Fairchild Semiconductor

Fairchild Semiconductor Division Plating Facility, Mountain View, late 1960s Architect: Simpson, Stratta & Associates Photographer: Marvin Wax © R&S limited; Courtesy of Kenneth G. Sletten

Working in Silicon Valley presented new construction challenges for Rudolph and Sletten. The buildings had to complement and adhere to the purpose of the companies themselves. In other words, the buildings had to be just as high-tech and cutting edge as the products that were being produced within their walls. Sletten remembers building some of the first clean rooms and “super” clean rooms. One of the first was for semiconductor company Advanced Micro Devices (AMD).

Video: Sletten explains the challenges of building some of the Valley’s first clean rooms, particularly for AMD

Memorex Corporation “Building on the Hill” Research Facility Bldg IV, Santa Clara County, 1969 Architect: Simpson, Stratta & Associates Photographer: Marvin Wax © R&S Limited; Courtesy of Kenneth G. Sletten

Today corporate campuses with open work spaces, gourmet cafeterias, gyms, and health spas, housing employees from companies like Google, Facebook, and Microsoft are standard fixtures in Silicon Valley. However, in 1971 a campus for anything other than a university was a novel idea.

Memorex is considered the first corporate campus in Silicon Valley and one of the first in the United States, an idea at the time conceived by CEO Larry Spitters and the architectural firm Simpson, Stratta, & Associates. Memorex, known as the “Building on the Hill,” sits upon fifty-one acres of what used to be an onion farm. Sletten explains that when the land was first purchased, it was abundant with onions and before Rudolph and Sletten could break ground, they had to harvest the onions themselves. It was a project that took two and a half years to build and was home to Memorex’s warehousing and corporate offices. Ken recalls that during the final inspection, the very day before they were to hand over the keys, an electrical short in the building knocked-out the power for the entire city of Cupertino. Both Ken and Dick chuckled at this, but remember at the time it was no laughing matter.

Video: Sletten talks about Memorex, Silicon Valley’s first corporate campus.

Sletten notes that in every construction project, there are two factors that can change the overall design: schedule and budget. To keep up with the rapid growth of Silicon Valley companies, Rudolph and Sletten adapted their business techniques to ensure that they could complete any given project on time and within budget. Rudolph and Sletten originated techniques such as fast-track scheduling, GMP or Guaranteed Maximum Pricing, rolling schedules, and fly specking to guarantee quality service and to meet the exact needs of each client.

Another unique feature about building in Silicon Valley is the amount of electrical and mechanical elements that go into each project. Sletten explains that fifty percent of any given project in the Valley is electrical and mechanical. Therefore the importance of building relationships with subcontractors who specialize in these fields and implementing education and safety programs for their employees was crucial for construction in Silicon Valley. Ken explains, “We had and have today a rigorous training program to fill the gaps and especially in electrical and mechanical and construction for all our supervisors.”

HP Garage Restoration Project: (Left) January 19, 2005. A Rudolph & Sletten truck is parked in front of 367 Addison Ave. at the beginning of the garage restoration project. Rudolph & Sletten were the contractors selected by HP for the project. (Right) Completed project, taken in December, 2005. Photo: Steve Castillo Photography; Courtesy of Hewlett-Packard

Video: Sletten talks about his and Rudy’s long time partnership with Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard

Rudy and Ken developed a special partnership with Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard, having worked on numerous buildings for HP throughout their long career. Given their relationship, it seemed only fitting when Dave Packard asked Rudolph and Sletten to spearhead construction of the Monterey Bay Aquarium, and a no-brainer when it came time to restore the now land-marked HP house and garage in 2005. Click here to read the full transcript from Ken Sletten’s oral history.