Webb McKinney

Philip E. Meza

Coauthors Becoming Hewlett Packard: Why Strategic Leadership Matters

HP was once famous and admired for its culture. The “HP Way” shaped several generations of companies in Silicon Valley and beyond. HP’s culture has been a source of significant advantages and challenges for the company under many different leaders. In this article, we can trace the lessons from where and how HP’s culture has supported the thrust of its strategy, and discuss where and how its culture conflicted with its strategy.

When Hewlett-Packard split into two companies in late 2015, it was 15 years overdue. Hewlett Packard Enterprise got the computing systems assets and IT services and software businesses, while Hewlett Packard Inc. got the imaging and printing and PC businesses. But which elements of HP’s corporate culture would the newly separate companies want to keep? HP’s culture, once widely admired, fragmented during the decade and a half of large acquisitions and acrimonious leadership changes prior to the 2015 split.

The interplay between HP’s culture and strategy had a vital role in HP’s successes and failures. Research in the new book, Becoming Hewlett Packard: Why Strategic Leadership Matters (Oxford University Press) by Robert A. Burgelman, Webb McKinney, and Philip E. Meza, shows the crucial ways that corporate culture impacted each CEO’s ability to execute on strategy, and how strategy and corporate structure, in turn, influenced HP’s culture.

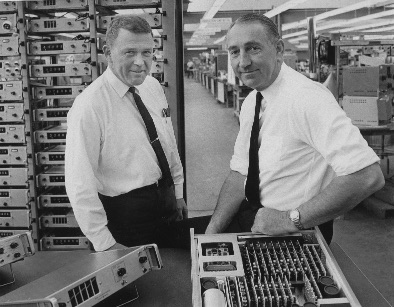

Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard.

HP has existed for nine decades and navigated several major technology and market shifts. It is very hard for technology companies to survive these fundamental changes. For HP, however, doing so was easier than surviving the cultural challenges that resulted from some of those shifts.HP’s original culture was shaped and maintained by its co-founders Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard. The essence of HP’s culture, known as the “HP Way” could be expressed in a few straightforward objectives including self-financed growth, highly differentiated products, respect for employees, and good corporate citizenship. As HP grew, Bill and Dave created independent divisions to encourage innovation and accountability, while the CEO drove overall strategy. The HP Way, under Bill and Dave, was supple enough to help the founders steer the company through the earth-shaking shifts from vacuum tubes to transistors to integrated circuits. HP ably incorporated all of these new technologies into their core business of designing and manufacturing highly differentiated test and measurement instruments. Under Packard’s and Hewlett’s tenures as CEO, HP became a world leading test and measurement company.

By the time the founders handed over the reigns to longtime HP executive John Young in 1978, HP earned almost half its revenue from computer systems. Over time, as a result of the independent division model favored by Bill and Dave, however, three of HP’s independent divisions had developed separate, incompatible 16-bit microprocessor computer systems. When the state of the art shifted to 32-bit microprocessor technology, Young tasked HP Labs to create a new 32-bit architecture to replace the incompatible 16-bit systems and to make HP a leader in computers. To accomplish this huge effort, Young took control of the budgets and discretion that HP’s powerful division heads prized. This conflicted with HP’s longstanding independent division model and was viewed as a violation of the HP Way by many. Others felt this was necessary to make HP a successful computer systems company.

Young’s massive investments in the 32-bit system, called HP PA/RISC, hurt HP’s bottom line. The company’s stock price underperformed its competitors’ as Young ploughed more money and talent into developing the new system. Frustrated by HP’s performance and buttonholed by employees unhappy with Young’s complex operating models, board Chairman Packard got involved. He forced Young to simplify HP’s operational model to be more consistent with HP tradition. In 1992 Young retired from HP before the returns from HP PA/ RISC fully paid off. Young’s successor, HP veteran Lew Platt, had orders from Packard to “restore the HP Way.” To do so, Platt instituted an even more decentralized operating model that delegated strategy to operating units. Platt, however, did not develop an overall corporate strategy.

For the first few years of Platt’s tenure, these problems were not apparent because revenue from HP PA/RISC finally rolled in and HP’s profitable new printer business took off. This success, however, was fleeting. HP missed the emergence of the internet, and “Wintel” industry-standard computers began to replace HP’s proprietary architecture systems, reducing HP’s differentiation and profits. The lack of an overall strategy and the weak corporate controls created major conflict between divisions. HP’s performance lagged compared to its internet bubble fueled competitors. Platt proposed splitting the company into four independent companies (test and measurement; printers; computing systems; and PCs). HP’s board of directors, a “founder’s board” used to taking direction from Packard, who had died, and from Hewlett who was unwell and no longer involved, struggled with this decision. Ultimately, they decided to spin-off only the test and measurement group and in 1999 looked for a new CEO from outside to lead HP. By the end of the Platt era, HP was struggling without an overall strategy, but still had most of the original HP Way culture intact.

HP’s next four CEOs, all outsiders, dramatically changed the culture of the company. Their tenures were marked by strong top-down strategy, growth through major acquisitions, and ongoing layoffs to improve profits. These progressively fragmented HP’s once strong culture. Platt’s successor, Carly Fiorina, a star sales executive from telecommunications company Lucent, purchased Compaq, a company nearly the same size as HP but with a very different culture. Unfortunately, HP did not execute well under Fiorina. The company missed several quarterly profit estimates and its share price suffered. HP’s board of directors, itself becoming increasingly dysfunctional, lost faith in Fiorina and dismissed her while they again looked outside the company for leadership.

They selected Mark Hurd, the CEO of NCR, who had a reputation for operational excellence. Hurd imposed on HP a strong focus on efficiency and cost reductions. After improving HP’s operational performance and profits, Hurd made multiple large acquisitions in search of growth. He also replaced many longtime HP executives with outsiders who managed in an aggressive, operational style. These changes created growing cultural divides. Hurd delivered operational and stock market success that had eluded HP for several years, however, his tenure was cut short by a personal controversy. Hurd’s successor inherited a much larger and more complex company that was struggling to grow.

The next executive selected to become CEO, software executive Léo Apotheker, formerly from SAP, was the third outsider in a row to lead HP. Apotheker was shocked by the low morale and fragmented culture he found when he arrived at HP. He feared the company’s product offerings were undifferentiated and quickly becoming irrelevant to the market. Apotheker thought fast action was needed. He made a large acquisition of a (subsequently troubled) data mining company and publicly mused about splitting off HP’s PC assets. This unnerved customers, and HP’s board of directors, which by this time had become highly dysfunctional. They fired Apotheker after only 11 months on the job.

Meg Whitman, then a new member of HP’s board, and past CEO of eBay, was selected to succeed Apotheker. Whitman initially determined HP was still “better together,” and kept the scale and scope strategy Fiorina and Hurd pursued. Whitman focused on improving HP’s operations and business performance and aligning these with its culture. She reinforced the centralized leadership model used by Fiorina and Hurd. Whitman, however, moved top executives out of plush offices and into cubes. She ditched the executive parking lot and provided much more transparent interactions with leaders and rank and file employees. In doing so, Whitman restored many of the “soft” elements of the HP Way that Packard and Hewlett would have welcomed, while reestablishing centralized corporate strategy, operational excellence, and accountability. However, HP’s culture remained an admixture of elements from the prior major acquisitions. After stabilizing the company and improving performance, Whitman still was unable to make this large and complex corporation grow sufficiently. Whitman decided to split HP into two companies, echoing Lew Platt’s proposal in 1999.

These new companies will have to establish their cultures and align them with strategy and structure each thinks best for their businesses. This is not easy to do. Even giants like Dave Packard and Bill Hewlett struggled with this after getting right for decades. Subsequent talented leaders at HP all struggled to shape their HP Ways to align with the strategies and structures they inherited and then constructed. If the new HP companies can create HP Ways that help them grow, they too might become long-lived like the company Bill and Dave created.

This blog was written in connection with the CHM Live show “The Six Transformations of Hewlett-Packard: A Conversation with Becoming Hewlett Packard Authors Webb McKinney and Philip E. Meza,” moderated by Software History Center Director David C. Brock. The event took place at the Computer History Museum on February 16, 2017.

..

This event was broadcasted live via Facebook Live. Watch all future events live on the Museum’s Facebook page.