David Morgenthaler in his Menlo Park, California, office on February 22 2013. Credit: CDernbach/Wikimedia Commons/CC-BY-SA 3.0

David T. Morgenthaler (August 5, 1919–June 17, 2016) was a towering figure in the first generation of global technology venture capitalists. He entered the business of investing, in fact, before “venture capital” permanently joined the financial lexicon. From the time he entered the field at the age of 48, until his death on June 17, 2016, at the age of 96, Morgenthaler led $3 billion of investments in more than 300 companies. Early investments in Apple and Siri were among them.

Many investors of Morgenthaler’s generation were successful. Many discovered or helped dozens or hundreds of companies succeed. Many, like David, have given rise to a second and even a third generation of high-achieving investors—in this case, the notable Silicon Valley figure Gary Morgenthaler.

Few, however, may so singularly represent the unique qualities of individuals who were born in the Great Depression, were tempered in combat during World War II, and who were forged into business-savvy industrialists in a post-war boom—an era that provided unique opportunities for both financial impact and social leadership.

David Morgenthaler was one of those individuals.

I got to know David, and to become his friend, late in his life. On December 2, 2011, I had the honor of taking David’s oral history. I’ll never forget it. David was 92. He acted about 52. As we sat down for the interview, he opened a can of Diet Coke. He talked for more than four hours. He never got up. He never took a break. He never stopped talking. He kept asking how I was holding up. He finished the Diet Coke.

He was tough as a boot.

I’m 40 years younger. It exhausted me. But I was determined, by golly, that if, at 92, David could sit and tell his remarkable story on video for four hours, I’d be right there to interview him. The transcript runs 56 single-spaced pages. It was one of the most fascinating afternoons ever. Thankfully, his oral history a permanent part of our archive now.

Three stories stand out from the interview: the beginning, the lessons in the middle, and the results at the end.

David’s early life and education represented modest, character-shaping roots. He was born on August 5, 1919, in the small town of Chester, South Carolina. To put into perspective how distant that seems from today, consider this:

By the age of 6, Morgenthaler was working in the Carolina cotton fields of his grandfather. By the time he got to high school, an English teacher told him he was good in English but also had a particular aptitude for technical things, and he ought to consider being an engineer. He asked around and learned that MIT was a good engineering school.

So he applied, and, at the age of 17, he went.

He learned that a freshman engineering major at MIT needed to know a few things to do well—like, say, calculus. He hadn’t had calculus in high school. There were other gaps in his education, too. In describing his first year, he said, “I’d never seen a bad grade until that point. My first three months at MIT were a rude shock.”

How did he overcome that?

“Work,” he said. “Plain and simple.” By 1941 he had earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in mechanical engineering, and captained the MIT swimming team.

And then the war came.

The day after Pearl Harbor, Morgenthaler entered the US Army Corps of Engineers. By 1943 he was in North Africa building airfields. He went in as an Assistant Regimental Engineering Officer. Within months he was promoted to Captain.

His command was 178 men. He was not yet 25.

He learned some more lessons. And this is part two of the story.

“I learned,” he said, “it was one thing to give an order, and another thing to get it carried out. This has greatly influenced my philosophy on leadership.

”I told my men, ‘We’re here to do a job. We’re going to carry out our mission.’ As a leader, I felt my men had to understand that. You’re going to carry out the mission—over their dead bodies or over your dead body if need be, but the mission is going to happen.”

”But I also knew I had to personalize it, to put humanity on it. I said, ‘If you do that, if you cooperate, I’m going to do everything I can to get you home in one piece—not killed, not wounded.”

”I’m also going to do everything I can to make your life here as less bad as it can be. There’s no making it good, but I’m going to make it less bad. For example: army food is bad. But if you see you’re getting the best food out of the 13 mess halls in the regiment, then you feel relatively well off. I saw to the little things like that, too.”

David informed his cooks they’d be digging ditches for landing strips instead of cooking bacon for breakfast if they burned the pork chops at dinner. He made his officers eat in the same mess hall as the enlisted men. He saw to it that his senior staff was housed and in bed each night only after their men had turned in.

“I ran what was considered the strictest company in the regiment. But the feedback from our commanding officer was that we also had the highest morale,” he said.

David gained a reputation for fairness. He was given a second job: criminal prosecutor in the regiment’s courts martial. Near the end of his service, David was ordered by his commanding officer to prosecute a group of soldiers, including a lieutenant, on charges that David felt were unfair.

“I went to the colonel and said, ‘Colonel, this is not fair. I’m a troop commander. My men look to me to look after them if they’re being mistreated. This would be a mistreatment of these guys.’” But, in David’s words, the colonel “got stubborn on it.”

“I said, ‘All right, sir, but you cannot force me to court martial them, and you’ll have to get someone else to sign the charges. Furthermore, I’ll volunteer to defend them if they want me. If I defend them, I guarantee they’ll walk out free men and you’re going to look silly.’”

The colonel did find another prosecutor. David did serve as the volunteer defense attorney. The group was acquitted in 35 minutes. His commanding officer met him at the courtroom door, cussed him out—then slapped him on the back and bought him a drink.

“That’s what you do,” he said, “when you care about your men. That was what I got out of my army experience. You run a group, and you have to run the group. It taught me a lot about leadership.”

That’s the second of the stories—the leadership lessons in the middle.

Which brings me to the third part: the results at the end.

Over the next 30 years, Morgenthaler refined his army experience and his increasingly keen instincts for business into a corporate career and then into a career in the emerging field of venture investing. In 1968, at the age of 48, he left a senior post in the private equity firm J.H. Whitney & Co. to set out on his own as the founder of Morgenthaler Ventures in Cleveland, Ohio. Soon after, he opened a second office in Silicon Valley.

Venture capital was just getting started, and it was not an overnight success. In the late 1960s, a number of leading figures in venture investing sought to form a Washington, DC-based trade association, to make a policy case for legal and regulatory changes that could help new ventures and the investors who backed them. The group, eventually known as the National Venture Capital Association, appealed to Morgenthaler for help. He agreed to become a co-founder and founding director—not because of any particular affection for Washington and politics, but because the role fit with both his practicality and his natural attraction to lead from the front.

“I never wanted the life of a politician, but I was and am vitally concerned with how you govern things. People talk about ‘the reality’ and ‘the situation,’ and those are big words. People see ‘the situation’ the way they want. I may look into it, and I may not like what I’m going to find. But I’ve got to deal with it the way it is. That’s how I approached Washington,” he said.

Morgenthaler’s practical approach found a particular focus: to communicate to Congress and to executives of the US Treasury the importance of entrepreneur-led businesses. “It was largely an educational job,” he said, “and I liked the role of being an educator.”

By the mid-1970s, the effort Morgenthaler led had resulted in two major changes in federal law that have shaped US investment policy for nearly 50 years—a rollback in capital gains tax rates, and the modification of the ERISA statute’s “prudent man” rule to allow pension funds to invest in venture capital firms. These changes ignited the modern venture capital industry.

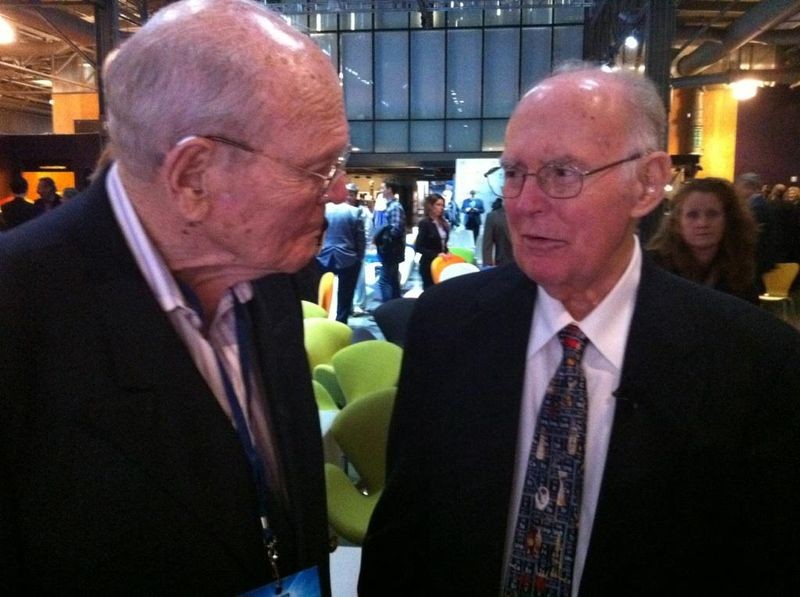

Left to right: David Morgenthaler, 96, and Gordon Moore, 86, at a 50th anniversary celebration of Moore’s Law on May 11, 2015.

Morgenthaler served on the boards of more than 30 companies ranging from computing at every level to biotechnology and life sciences. In his final days, he was reviewing a possible future investment by testing a digital medicine app on his mobile phone in his hospital room.

Intellectual challenge, hard work, diplomacy and, ultimately, financial success were major themes of David Morgenthaler’s business life. Clearly discernible from his oral history is the arc of US technological and industrial progress, innovation, financial experimentation, and the emergence of the startup age. It is practically a case study in how venture capital took hold and grew as an economic phenomenon after World War II. Finally, on a personal level, his story is a poignant distillation of the principles behind what journalist Tom Brokaw labeled “the greatest generation.”