Original location of the Computer History Museum at NASA Ames, Moffett Field. Hangar One in the background.

Before moving up a couple of exits on Highway 101N, to our current location at 1401 North Shoreline Blvd., CHM and part of its collection were housed in a WWII-era Quonset hut at Moffett Field. I had got to thinking about CHM’s former home a few weeks ago when space shuttle Endeavour, piggybacked to a jumbo-747, paid homage to Moffett-based NASA Ames Research Center with a close to the ground flyover of the site. The closeness of CHM with Moffett has led to affiliations with some of the agencies centered there, including NASA Ames and its partners. One affiliation is with the SETI Institute (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence), a non-profit with close ties to the greater SETI community, and NASA in particular. Sometimes beleaguered by critics as “scientists trying to chase little green men,” in its defense, the SETI community has a history of well-known, highly-regarded scientific backers and sound technical implementation of its search efforts.

The first two initial meetings of the SETI Science Working Group (SSWG) were held at NASA Ames in early 1980, and as a result of the initial rounds of SSWG meetings, a list of conclusions and recommendations were summarized and presented in NASA Technical Paper 2244 which laid foundational framework for NASA SETI’s mission moving forward. A consensus among Group members formed that if intelligent, extraterrestrial life existed that was capable of transmitting signals across the ether of space, they would likely emit radio signals detectable by available instrumentation on Earth. The Working Group concluded that searching for microwave signals in the electromagnetic spectrum was the best available option given existing resources and technological capabilities.

SETI equipment at DSS13, Goldstone, California, consisting of (Left to Right) a power conditioner, VAX 11/750, tape and disk drives, and the MCSA 1. CHM# 102657160/Courtesy of NASA Ames

As a result, the need to have equipment capable of analyzing the colossal amounts of data that would be necessary to sift through became a high priority. NASA SETI partnered with the SETI Institute and Stanford professor Dr. Ivan Linscott’s team of grad students, and work began on a prototype unit that would digest and analyze the data. The result of this project was the Multichannel Spectrum Analyzer (MCSA) 1 which was ultimately hooked up with a DEC VAX 11/750 for signal detection algorithm development and field testing. The MCSA 1 began its service in 1985 at The Goldstone Deep Space Network in the Mojave Desert.

A milestone at Goldstone occurred when the MCSA 1 easily detected a signal from Pioneer 10, which was 5.3 billion kilometers from Earth at the time. Other, existing NASA data acquisition systems installed at the 26-meter Goldstone antenna were incapable of detecting the signal, but the MCSA 1 had no trouble with this task. Incidentally, you can see the class of minicomputer that controlled a Goldstone telescope in the Museum’s Revolution exhibit.

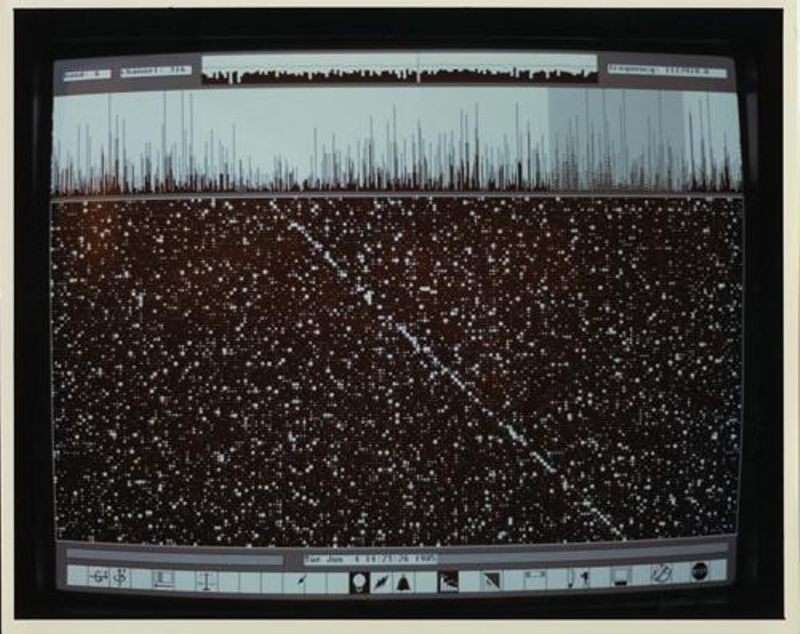

A screenshot of the MCSA 1 display as it detects the Pioneer 10 signal on June 4, 1985. CHM# 102657164/Courtesy of NASA Ames

In 1989, the MCSA 1 was transferred to the Arecibo telescope observatory in Puerto Rico. While at Arecibo, the MCSA 1 conducted the most sensitive SETI observations up to that time. These efforts were crucial in this stage of developing signal analysis systems fine-tuned and specialized for ET signal detection. The computing power of the MCSA 1 relied on implementation of a short prime factor Fourier algorithm, specifically Discrete Fourier Transforms (DFT). It allowed for rapid analysis of multiple channels in small bins, which was crucial given the vast amounts of involved data. Ultimately, the MCSA 1 and its components, including DFT boards, divided a 37 kHz signal into 74,000 channels. After its retirement from active duty, the MCSA 1 was transferred to CHM’s permanent artifact collection.

Successive generations of MCSAs were built upon the experiences gained from this first effort, but even these more advanced versions have yet to receive a confirmed ET signal. Still, progress continues towards the possibility of receiving one. One such complementary effort, launched by NASA in March of 2009, is the Kepler spacecraft. One Kepler mission has been to locate Earth-like planets in a targeted portion of our home galaxy.

NASA Ames is the lead center for the mission development, operation, and analysis of the Kepler project, with a primary goal of identifying rocky exoplanets in the Goldilocks, or habitable zones, of their host star or stars. These planets must be at just the right distance from their host stars where temperatures are neither too hot nor too cold to sustain life as we know it. Kepler findings to date, and in the future, have and will prove to be a cornucopia of information for SETI research. Future SETI observations will not only be able to target searches for signals at areas where known exoplanets exist, but also further refine those searches to planets (think Goldilocks-zone planets) potentially capable of nourishing civilizations that may have had or currently possess signal dispatching technologies from which SETI projects have long sought to receive.

Aerial view of the Arecibo radio telescope, the world’s largest, after a major upgrade circa 1998. CHM# 102651964/Courtesy of NASA Ames

There are plenty of ways for you to get involved and help out in future efforts. The well-known SETI@home distributed computing project, which offloads analysis of data to internet-connected, idle home computers, has used data from the Arecibo facilities since the late 1990s. Although budget shortfalls have hampered the project at times, it is one of the most well-known and widely participated in projects of its types.

For those interested in a more active approach and want to actually crunch data themselves, try out www.planethunters.org. Planet Hunters is a citizen-science project, with ordinary citizens contributing their time to sifting through data from Kepler. According to Planet Hunters, “while computers still struggle with this seemingly basic task… humans… have the capacity to recognize if something is odd or unexpected.” Planet Hunters allows a grassroots based team of observers to identify potential exoplanets around neighboring stars by spotting regular, momentary dips in a star’s brightness. This can indicate a large mass, possibly a planet, orbiting around the star.

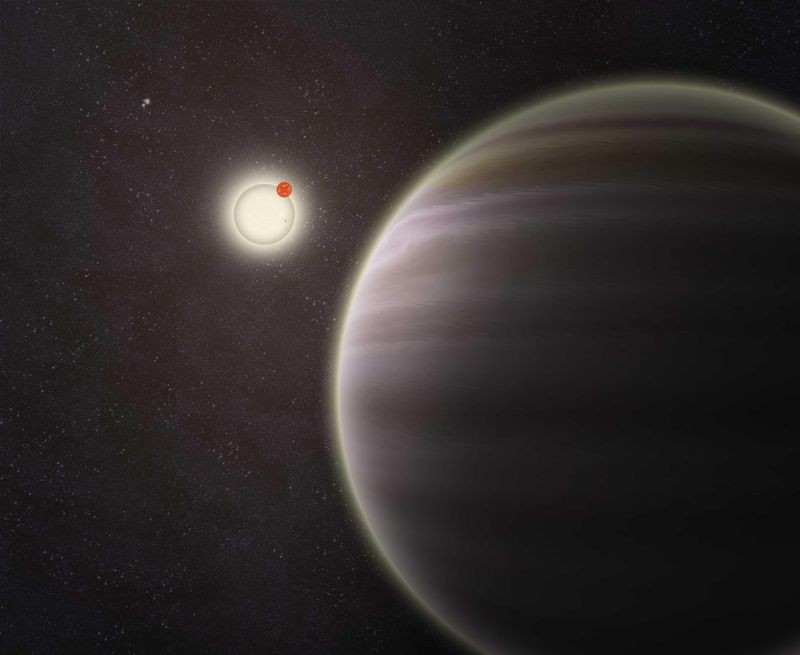

An artist’s illustration of PH1, a planet discovered by volunteers from the Planet Hunters citizen science project. PH1, shown in the foreground, is a circumbinary planet and orbits two suns. Credit: Haven Giguere/Yale

I signed up for Planet Hunters several months ago, and so far, I have only classified 25 stars. That puts me at 0.02% complete for this set of data. Not bad for the hour or so I put into it though. The new sets of data that Kepler is churning out as it continues to survey the sky could keep me busy for years. The data is reviewed and potential transits are logged by multiple citizen scientists, and while not guaranteed sources of analysis, think of it as crowd-sourcing in the name of science, or for the ultimate prize of finding what may be a planetary home to those “little green men”.