Hans Tung, managing partner of GGV Capital, and Carmen Chang, general partner and chairman and head, Asia at NEA speak with the Exponential Center’s Marguerite Gong Hancock.

Remember when “Made in China” was synonymous with a cheap toy or electronic knockoff? Those days are long over. Chinese tech firms, once seen as quaint or copycats, can now count Alibaba, Tencent, and Ant Financial in the world’s top 10 most valuable internet companies, alongside Alphabet, Facebook, and Amazon. And the country’s tech economy is taking on, and beating, global rivals. Chinese founders are pushing the edge with new business models and disruptive innovations . . . and venture capitalists from both sides of the Pacific are shifting investments in a big way with important implications.

Leading venture capitalists Carmen Chang, general partner and chairman and head, Asia at New Enterprise Associates, and Hans Tung, managing partner of GGV Capital, discussed Chinese history and culture, cross-country deals, big companies, and current trends during a panel sponsored by the Exponential Center at the Computer History Museum on June 20, 2018.

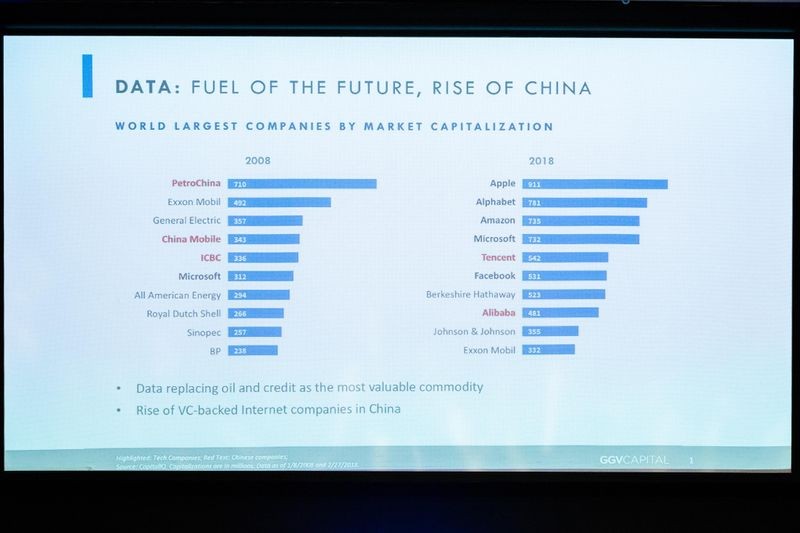

Hans Tung shares data on global economic shifts and the rise of Chinese tech companies.

Born in China, raised in Taiwan, and educated in the US, both Carmen Chang and Hans Tung developed a global outlook when they were still in their teens. Both were fascinated with history, Carmen pursuing a master’s in modern Chinese history, and Hans avidly exploring the clash of civilizations outside of his studies in electrical engineering. The combination of historical context, language skills, and personal connections with China were valuable to their early employers in law and finance. And, their experience working with Chinese entrepreneurs and companies—Carmen at storied Silicon Valley law firm Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati, and Hans for Goldman Sachs, a Taiwanese startup, and a Chinese company—made them uniquely suited to engage with China as venture capitalists.

Rooting the discussion in history, Carmen Chang described the Chinese investment landscape of the mid-1990s, when systems, patterns, and issues were set in place and addressed that are still important today. This was a time when infrastructure and semiconductor companies—the precursors to technology growth in the United States—were, in China, actually developing at the same time as internet companies. US companies like Goldman Sachs and Google were not sure how to invest in state-owned enterprises. Carmen helped incorporate the Taiwanese company Foxconn, which produces iPhones in China and is the largest contract manufacturing company in the world, and she also met the challenge of structuring a deal that would reassure Michael Dell and the US government that patented technology would not be stolen. Chinese engineers were being trained in American schools, the Chinese diaspora began to invest in Taiwan and mainland China, and joint banking ventures were formed. The first company founded and based in the United States with extensive operations in China, UTStarcom, was brought together by Masayoshi Son, who connected a team from Taiwan and another from China with the founder, with whom he had worked at a Berkeley bakery while in college. Son later founded SoftBank, the multinational conglomerate that owns Yahoo and Sprint.

Carmen Chang describes the founding of UTStarcom and early US investment in China.

Hans Tung identifies that same era, the mid-1990s to the early 2000s, as the time of apparent Chinese copycats, but he argues that in truth local solutions, a drive for efficiency, and the scaling facilitated by the internet led to innovative business models in e-commerce firms. What he learned in China helped him identify US firms in which to invest, like Poshmark and Wish. He also makes the case that it is not accurate to describe Alibaba as just the “Chinese eBay.” Due to the lack of credit cards in China, its business model is based on seller advertisements rather than charging for transactions like eBay. Hans sees a common drive and sense of mission in the three generations of Chinese entrepreneurs that he has observed, leading to huge market capitalizations for solid Chinese companies that can not be dismissed as part of a bubble. Xiaomi, whose recent Hong Kong IPO raised $4.7 billion at a valuation of $54 billion, is the perfect example. It is the only startup founded specifically to produce a smartphone from “scratch.”

Hans Tung explains why he was an early investor in Lei Jun’s company Xiaomi.

Xiaomi’s Mi phone, Hans claims, is different than an iPhone because, unlike Apple, the Chinese company seeks out and responds quickly to customer input, particularly from geeks and “Mi Fans,” leading to weekly upgrades. It is this kind of commitment, along with long work hours and a seeming disinterest in work-life balance, that he believes drives Chinese entrepreneurs to build companies that will last for the long term.

Both venture capitalists see incredible opportunities in China in the near future for the consumer internet sector as well as disrupting traditional industries and companies that embrace innovations in storage and artificial intelligence. Carmen notes that NEA’s areas of focus include healthcare technologies, services, and pharmaceuticals. The firm is also betting big in artificial intelligence and is interested in enterprise and AR/VR, particularly in media production. Hans says that GGV is funding consumer-focused companies, wants to leverage their US enterprise experience in China, and is interested in “frontier tech,” such as artificial intelligence, machine learning, autonomous driving, drones, augmented and virtual reality, and self-driving cars. But, while the cross-cultural shifts in technology and investment are exciting, and profitable, both Carmen and Hans are concerned about the high level of distrust between the US and China in the current political scene with its confusing policies that make it hard to know how to plan and adjust.

Carmen Chang describes common misunderstandings between the US and China.

With a balanced perspective on both countries, Hans and Carmen offer hope that eventually collaboration will prevail over divisive trade wars. In the short-term, Hans offers his thoughts on how China will respond to Cold War rhetoric from the United States: find different trading partners and become more self-sufficient. But, as China unleashes the creative energies of its latest entrepreneurs, perhaps the passion and drive to create something new that founders share throughout the world will transcend national politics and cultural barriers. With the dramatic ongoing shifts in China’s tech and venture capital sector only time will tell, but Carmen and Hans are both optimistic about the future. Perhaps it’s safe to bet on them.

“Techtonic Shift: China’s Rise in Venture Capital and Tech: NEA’s Carmen Chang and GGV Capital’s Hans Tung in Conversation with the Exponential Center’s Marguerite Gong Hancock,” June 20, 2018.

The Exponential Center at the Computer History Museum captures the legacy — and advances the future — of entrepreneurship and innovation in Silicon Valley and around the world. The center explores the people, companies, and communities that are transforming the human experience through technology innovation, economic value creation, and social impact. Our mission: to inform, influence, and inspire the next generation of innovators, entrepreneurs, and leaders changing the world.