Today we take mobility for granted. When technical writer Steve Roberts decided to be a “high tech nomad” in the 1980s, it was a radical dream. Eventually his writings about the journey overtook his day job. He pedaled over 17,000 miles. This photo shows him with the first of his systems for typing while riding. He has a head-up display attached to his helmet, and in the handlebars are keys for typing. He became a mentor to many wearable computing pioneers.

People wear the technology of their time. The stone-working techniques that made weapons also shaped beads for the body. When weaving was new, the intertwined warp and woof that made water-tight baskets also formed clothes. Smelting produced daggers and bracelets alike. Some technologies started off wearable – Galileo’s telescopes were a spinoff from spectacle makers. The toothed gears of mills and clocks made their way first to pockets, and then to our wrists. Electronics followed as the quartz wristwatch, then the digital version. Electronic headphones and earpieces eventually joined spectacles on our heads.

Today, general-purpose computers have made it as far as the pocket watch stage. Yet aside from a few specialized applications like fitness trackers, our bodies themselves remain largely free of the smart tech that fills pockets and purses.

How will we ultimately wear the technology of our time, which is not only the computing power held in tiny standalone chips but their connection to each other, their intermingling in a world of shared knowledge that now spans the physical globe?

Apple and others, of course, are hoping that the proven format developed for mechanical technology, the wristwatch, has at least another incarnation left. Google’s Glass is a riskier bet that we’ll accept head-mounted displays as we eventually did eyeglasses and Bluetooth headsets. Smart clothing and various other ways of wearing computers are still at the geek fashion show stage.

There is another set of questions about what we might use wearable computing for. Why bother? What’s the killer app that will make us put down our smart phones? There are also pivotal decisions about how we want wearables to fit into our social and everyday lives – and which deeply affect the design of the devices themselves. How can people know whether they’re being filmed? That a wearer is paying attention to them? Should wearables be subtle servants – an occasional whisper in our ear, a reminder in the corner of our eye – or offer deep immersion in the most powerful information access possible?

Until recently all of these had literally been academic questions, because the technology wasn’t ready for prime time. Early wearable computers were good enough for decades of hands-on experiments in various research groups, or specialized military and industrial applications. But those wearable rigs were too bulky, hot, isolated, or hard to use for a consumer product. And yet, the promise of being able to navigate information seamlessly, everywhere, inspired a few techies to keep working on those issues decade after decade as chips, batteries, and interfaces improved.

The traveling exhibit that we’re hosting this summer, On You, may be the first to tell the story of how wearables evolved from crude hand-hacked rigs to the sleek wannabe fashion of Google Glass and modern smart watches. Showing consumer, professional, and home-made devices including early Google Glass prototypes, On You explores the four key technical hurdles to making a consumer wearable computer: power and heat, networking, mobile input, and displays. Have they been solved? Come find out, and discover the technology that yearns to be on you!

The exhibit was curated by design researcher Clint Zeagler and wearable pioneer Thad Starner from Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech), and has been displayed at conferences, the Deutsches Museum in Munich and other German locations including Angela Merkel’s office. CHM is its first US museum stop. It will be on display from June 30 until September 20.

The exhibit came to us because of an oral history I did more than a year ago with Starner and another pioneer of wearable computing, Greg Priest-Dorman. Both of them had been hired for Google Glass partly because they had been wearing computers every day in public for over 20 years. Even more important, they were two of the core group who had put in the tens of thousands of hours of soldering, experimenting, designing and programming that has finally gotten the technology ready for the rest of us to try.

Greg Priest-Dorman with an audio wearable computer, 1990s. Courtesy Greg Priest-Dorman

Thad and Greg started “wearing,” as they term it, independently. But since linking up in the mid ‘90s they have been colleagues for nearly two decades, and co-founded a company to sell wearable computing kits. Together they have seen consumer wearables grow from a wild idea to an almost-industry, one with billions of investment from of the biggest tech companies in the world. All it needs is customers.

Thad was a member of “the Borg” at the MIT Media Lab, a group of students and wearable pioneers who tested out their ideas by wearing their rigs in daily life. He co-founded Charmed Technology to make several products including a wearable computer kit, the CharmIT, and is a founder and director of the Contextual Computing Group at Georgia Tech. He is a technical lead at Google Glass.

Greg was the System Administrator and Lab Coordinator for the Computer Science department at Vassar College for many years while he experimented with wearables. He was also an employee of Charmed Technology, hired to design and build the CharmIT kit. He is now a member of the Google Glass team.

When I interviewed Greg and Thad, I was captivated. They talked about technology, but also about the cognitive science behind how machines can best deliver information, and using computers as strength training for our own memory as well as pure geek fun like shoe computers that transmit business cards through the skin contact of a handshake.

But both men got interested in wearing computers for more serious reasons. Thad, as a memory aid in the classroom and to help him cope with a stutter in public speaking. Greg, to compensate for extreme learning disabilities that made reading difficult, combined with a back injury that made sitting painful. His computer would read emails and articles to him as he walked.

Starner (second from top left) and other members of “The Borg” at MIT

They had so many interesting things to say that we only got halfway through their story in the first session. So we did a second round. What follows are some excerpts from those two conversations, on topics from smart fashion and body networking, to how machines made life bearable for a severely injured adolescent. Later this summer we’ll post the complete interviews, and you’ll be able to read other stories about Thad and Greg’s nearly 45 years of cumulative experience wearing computers daily – like getting on a plane with wires and circuit boards strapped to your body.

GREG PRIEST-DORMAN: In ’97 we bought a house that was a little further away from campus… about a mile and a half. So for me the walk to work and the walk home– the walk to work was the time I would start listening to the email for the day, listening to my to do list from the night before, and starting to make comments about what I was going to and occasionally write emails while walking to work. [To Thad:] Your power port just came out, by the way, if that matters.

Thad Starner. Copyright Sam Ogden

THAD STARNER: Georgia Tech and CMU were more doing computers for inspection, maintenance, and repair, things where you put on a wearable computer like a uniform and you did your job during the day. And then you took it off at night. Most of the stuff we were doing at MIT was more like clothing or eyeglasses– stuff you put on and you wore as par of your daily life. It was much more like having a smartphone– a personal assistant that you used all the time instead of took off like a tool.

GREG PRIEST-DORMAN: I was unable to read…And that was hidden. So a big piece of, at least, my memory of my childhood was this covering about things that other people could do and I couldn’t do. And at the time, I would get tested at school. But dyslexia was not something that I guess people knew enough about. And now, it wouldn’t even be called that.

…

Unfortunately, in the summer between eighth and ninth grade, I was in a bicycling accident. And injured my neck and back very badly– was unable to walk for several years. In fact, at the time, they didn’t think I would be walking again.

But for that first year, I was in home-bound tutoring. And Mr. Hoyt came by and brought me a Tektronix scope and all this gear. By the time I then was returning to school, I was building biofeedback devices– simple stuff from books you could get at Radio Shack– galvanomic skin response things.

…

But he was giving me AP physics, which is wave forms and things. In addition to the oscilloscopes, he brought in EKG and stuff. We were looking at electricity in the body. I didn’t have use of my legs; I had very little use of my hands.

And I spend most nights wired up to the scopes, watching the little lights blink. And it was cool. And pretending I was in Star Trek or something. And that’s, probably, where I got very comfortable living attached to electronics.

So at the time I still was– so I got to Vassar, and it became pretty clear that I … didn’t really have a solid grasp of the alphabet.

And I went to the New England Children’s Hospital. They ended up looking back at some of the tests from school and saying, there’s clearly a thing here. And taught me basics of phonics and that kind of stuff to give me a better grasp on that.

And also found that I was doing some really interesting compensations that they thought they could use with other people. So a good percentage of time was also them asking me questions and looking at what I was doing to compensate for one thing or another and using that.

Priest-Dorman’s chord keyboard glove, hand-made from saddle leather. Here show being repaired.

So the locks come out of this because I was having a lot of trouble with staying focused during a class period. And I found– I did get– eventually got permission to be able to record the class, and I could listen to it afterwards.

But I still had to be able to recall the information in some structured way. And I went through lots of different techniques …And at one point, before I learned sign language– because eventually, I just signed in the back of the class to myself– I was doing things. I would find if I took something apart– something intricate– during the class and then took it apart later during review, that would bring the material back.

And so there was a period of time– having grown up in a hardware store. Dad had gone out of the hardware store, but we had parts. I brought back to college a bunch of door locks. And different classes, I would disassemble and reassemble the door lock.

But I would always sit in the way back corner because I didn’t want to be distracting to the class any more than, I guess, I was. So then, I’d be sitting there studying for peasant wars and political movements and social class and disassembling the lock. And oh, right! You know? Now, I couldn’t bring the locks into the test.

But I don’t know why that story was one that you particularly liked.

THAD STARNER: One of the things is about the memory, right? Because we both came to this from memory, in some sense.

THAD STARNER: So this is where we have some very interesting overlap. So he was doing all these manual tasks like the disassembling a lock and assigning parts of the lecture to it to have a memory of it.

I was, at the same time, being depressed about how much I was losing of my education at MIT. I remember, when I was in …ninth grade learning trig. And I asked my father for some help. And he looked at the work– now, this was a power engineer– he looked at the work and said, “I just don’t remember how to do this. Sorry.”

I’m like, “How can you not remember this? You’ve got to be using this sort of stuff in your job. You’re doing three-phase stuff that– it’s got to have trig in it.” He said, “No. It’s just, I don’t use the stuff. And since I don’t use it, I don’t remember it.” I resolved to not forget my lessons, completely naively….

It turned out to be a focus problem. So when I got head-up display, finally– this is 1993– I finally got a head-up display, and I could put the focus on the screen at the focus on the blackboard.

And suddenly, everything worked. I had a one-handed keyboard called a Twiddler– this is a Twiddler2– and it allowed me to type up to 130 words per minute in bursts. I maintained 60 or 70.

And it allowed me to take the most technical notes… and keep up with the professor and get the intuition…

Greg Priest-Dorman wearing Google Glass

THAD STARNER: But we also started making something called the Remembrance Agent, which would look at your typing, see what notes you were taking during this conversation, and pull up files that are relevant to the current conversation.

THAD STARNER:… I was panicked at the thought of having four professors sit in front of me, asking me all these hard questions on all these hard documents I was supposed to read. And I actually did read them all. And one the reasons why we pushed the Remembrance Agent was because I was terrified of my oral exam. The written didn’t scare me as much as the oral.

So I really wanted something that provided me information support in this face-to-face, sort of antagonistic, exam period. And so I had every single document that I was supposed to read scanned and OCR’d. And up on my eyeball at the time. And the Remembrance Agent running.

As all the questions came, I was typing them. And the Remembrance Agent was pulling up the references. I knew the references so well at that point that just seeing it come up would spur the right memory. And I’d say, as according to what Rosen says in this book, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah.

Right? I didn’t even have to pull it up. Just seeing it would remind me enough. And we go– these are generally three-hour affairs. At the end of it, at the very end, the professor who was supposed to be an observer in the room, just to make sure it was fair, looks me and says, Thad, you’ve been wearing your computer the entire time. Were you using the Remembrance Agent during the exam?

I said, well, yes. Yes I was. That’s the whole point.

And he looks at the other professors and says, do we think this is fair? This ended up with a half an hour argument, among these professors, about whether or not this was actually an unfair advantage. And the result that came out was, no, it’s not because for years, up to that point, I’d been wearing this as part of my daily life.

And so the qualifier exam was supposed to test you of how you’d actually be in the real world. Since I clearly was wearing this in the real world, it was fair.

…

GREG PRIEST-DORMAN: I loved the idea of the Remembrance Agent, but it never worked… for me at the time because…my wearable did not involve a head-mounted display. I was doing everything in audio output– Emacspeak specifically.

… Because I was working in auditory environment, I was looking at the way blind programmers code. And came to adopt techniques that others were using in using outliners and organization thoughts that way.

From FIDO (Facilitating Interactions for Dogs with Occupations), current Georgia Tech work on wearables for service dogs. The vest has GPS and can call 911 when the dog tugs in a particular way.

based on being able to zoom in and out, as I saw the blind community doing in order to keep what is essentially as a linear stream of data– the audio coming at you– useful at any point in time by being able to dig into it or pull back or zoom back from it in an outliner-type format….By ’94, I was using Emacspeak. ’95, I was walking around with it pretty regularly. And ’96… it was there, solid.

THAD STARNER: …what happened was Maggie Orth was being fitted for her wedding gown and looked down at her dress wondering how did they get it so shiny. She picked up this and was looking very carefully at it and suddenly realized it was silk going one way and silk with aluminum wire going the other.

GREG PRIEST-DORMAN: Actually– so, can I take this because of the weaving background?

THAD STARNER: Sure.

GREG PRIEST-DORMAN: So the warp threads have flat pieces of silver wire actually whirled around them. The weft threads don’t. So in one direction you’ve got conductive threads.

MARC WEBER: And this is common in saris too, right?

GREG PRIEST-DORMAN: Yes.

THAD STARNER: And so what she was looking at was she said as she’s getting fitted for her wedding dress, she says, somebody get me my multimeter. And sits down and start poking at her wedding dress and realizes it’s conductive. And it was only conductive going one way. And so for any self respecting computer nerd this is a computer bus and so she shows it to Remy and the next thing you know we’re at this conference sponsored by FedEx… and Remy the night before pulls up this crinkled scarf from his pocket, smooths it down in front of me and it’s coppery looking.

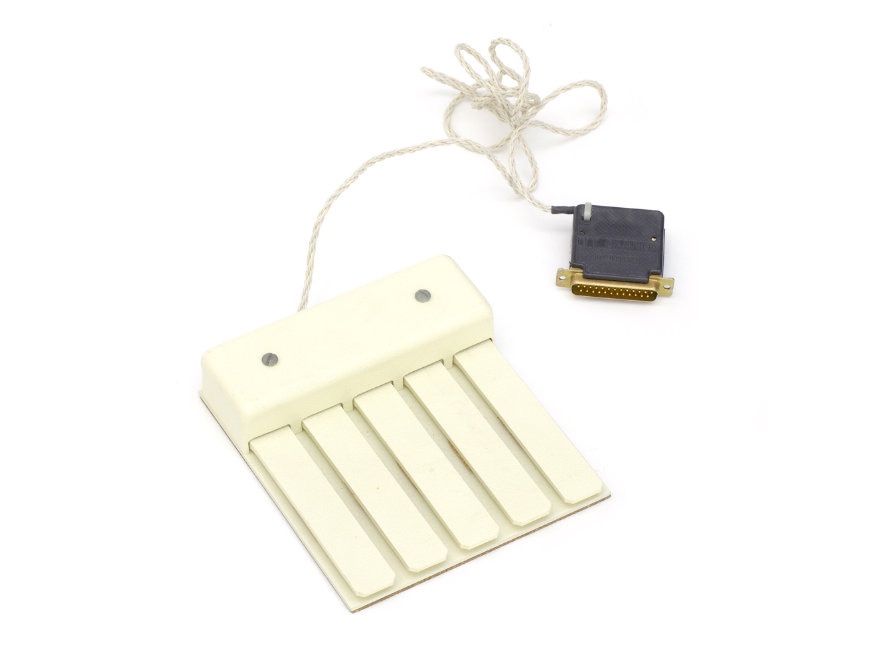

Chord keyset developed by Doug Engelbart and Bill English to go with the mouse, which they also invented, mid 1960s. Users could type any letter with combinations of keystrokes (chords) using one hand.

And he puts in a battery and suddenly this thing is flashing LEDs. And whenever he touches it, it makes sound. And I look at this going, oh my word, you surface mount soldered computer components to fabric. That’s neat. And he had two knit so that it was not just a switch, it was actually a capacitive touch switch. This is back before people had capacitive touchscreen everythings. But he had figured out a cheap way of doing this. And now he actually had a touch sensitive scarf computer.

While we were playing with it the night before, he even changed the constants so he could blow on it. It could sense you were blowing on it and change state. And he went even further with this, at one point Maggie and I were very interested in power and he started showing how you can actually transmit power remotely to these computers, which was exciting. That got the military all excited again. Because we were looking that you could do sensing at a distance… and so Remy showed how you could actually power the computers at a distance…very Tesla-esque.

THAD STARNER: Tom Zimmerman and Remy Post were showing how you could use near field radio to transmit data over your skin. So it had a great demonstration where people would have computers in their shoes and he’d have a display and as you shook hands with somebody you’d get the business card transferred over the handshake.

THAD STARNER: And as soon as I got in I was talking to Larry about this. And that’s where he turned to me one day and said, Thad, the reason we’re doing Glass is to reduce the time between intention and action. And my jaw hit the floor. And I said, that’s precisely the phrase I’ve been looking for the past 20 years. It describes perfectly this idea of short access time. This getting the idea out of your head into the real world to do something with it. And that’s what he’s been doing with these search engines– trying to make search as fast as possible. … [Then] Larry became CEO. And so Sergey took over the project and …one of the things that Sergey said early on is, I want as many of the people who have been wearing computers for more than a year as possible here. We’ll find something for them to do here. And so I ended up calling up Greg here and saying, hey, what are you doing? Never thinking I would get him out of Vassar.

GREG PRIEST-DORMAN: Well, Thad had tried regularly over the years to coax me down to wherever he was at the time– or over to wherever he was at the time. But a number of items aligned to make this one work out.

MARC WEBER: But you’re doing the hardware prototyping, as well. So… what kind of people were on the team? [Both] mechanical engineers and electrical engineers?

THAD STARNER: No… the people you want for the rapid iteration are oftentimes generalists. They can do anything, but not to fit and finish you want for a real product. I mean, I have this image in my head of Josh Weaver hot melting a projector onto Sergey’s safety glasses like this. I’m thinking, oh, my word.

Starner with an early prototype of Google Glass

GREG PRIEST-DORMAN: While Sergey was in them.

THAD STARNER: I’m just going to leave the room because I know that he’s got better hands than I do and I don’t see any other way to do this to actually make Sergey’s glasses. So, yeah, go to it.

THAD STARNER: So for me it’s all about raising the IQ of the planet. I’ve always thought that we could do a job of supporting human memory, having access to knowledge a whole faster, and having just-in-time information so you can get the information when you need it just before you need it. And also collaboration among people on a more subtle and continuous basis. …the ability to support each other in making decisions and providing knowledge at the right time without the barrier of distance. …I think we have the ability to make these systems where the access to information is much faster, much more subtle, and much more continuous, so that you really are using these machines as the intellectual extension of yourself.

People go, “Isn’t this going to be distracting, having it there?” And–

THAD STARNER: What we found is that sometimes, it gives you hyper focus.

GREG PRIEST-DORMAN: … it allows you that deep focus on an activity. And I think a lot of what the daily-wear folks discover– and one of things that’s exciting with Glass, and some of our Explorers are discovering this– is there is almost a mindfulness that comes out of it.

Instead of being distracted by all this stuff, you’re much more in control of that precious resource we have– our attention– and therefore, able to actually give it to others…if we can help people do wearables that way, it really is a benefit. And I come back to that religion thing, about how does it help you get through the day? At the end of the day–

There are number of practices, nonreligious ones, as well– I came at it from the religion side– a number of traditions which, at the end of the day, ask you to take some time to, in the modern sense, replay the movie of your day. Right? To curate those events in your day. www.nowtime.xyz I don’t know if doing the mental reinforcement of things that were significant to you, before going to sleep, affects memory. It certainly helps me have a handle on the week that went by and the years that go by.

If at the end of the day…because you’ve been wearing this device and helped by that device, you feel that you’ve been more able to interact with people, then I think we’re doing something that’s out there.