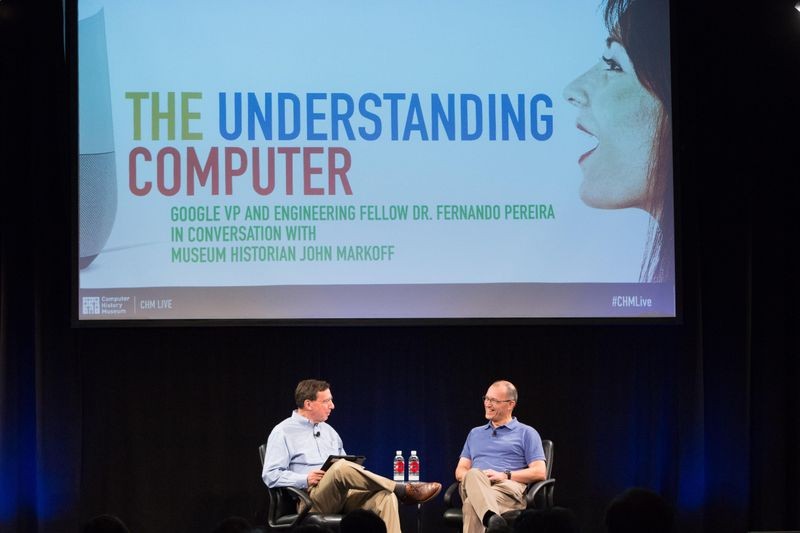

“The Understanding Computer Google VP and Engineering Fellow Dr. Fernando Pereira in Conversation with Museum Historian John Markoff,” October 10, 2017. Produced by CHM Live.

People may not know that the early days of artificial intelligence can be traced back to the 1950s, with the Turing test and the founding of the MIT AI Lab by John McCarthy and Marvin Minsky. Fast forward 60 years later and you’ll find a world where the possibilities of AI are endless. Innovators are applying AI to transportation, money, and even dating. But perhaps the most common sector of AI today are personal chatbots, such as Amazon’s Alexa and Apple’s Siri, commercially available to the masses. Google’s iteration of this is the Google Assistant, a personal virtual assistant that works across all your devices, including your phone, watch, laptop, and TV.

CHM Live guest and Google VP and Engineering Fellow Dr. Fernando Pereira leads a team of software engineers who are adapting the principles of linguistics and natural language understanding to machine learning, inching closer toward a chatbot that becomes more intelligent, conversational, and tailored to its user with every interaction, aligning perfectly with the Google Assistant tagline—“ready to help, wherever you are.”

On October 10, 2017, Pereira joined CHM historian John Markoff for an intriguing conversation about his background in the field, the challenges of teaching a machine to understand natural language, and why he thinks a breakthrough is needed before machine learning can advance to the next level.

Markoff kicked off the discussion with Pereira about how he got interested in AI. Pereira described his college experience in Portugal and how he found inspiration in the book Computers and Thought, by AI pioneer Ed Feigenbaum, as well as research papers by John McCarthy. Due to the struggling economy in his home country and the lack of opportunity in the UK, after graduating college, he accepted a job offer in the US at SRI (Stanford Research Institute).

Pereira’s professional career includes experience in both corporate and academic environments. He reflected on each setting and stressed the importance of long-term funding in research, especially since his work can take years before it yields usable results.

Google VP and Engineering Fellow Dr. Fernando Pereira explains the challenges and benefits of academic funding for natural language understanding.

Today, Pereira’s primary focus for his work at Google is utilizing the latest machine learning techniques to teach AI-powered machines to learn, understand, and comprehend so that it can think, communicate, and respond to humans, like humans. During the program, we played a clip from a previous CHM Live event, “AI and Social Good,” which featured Facebook Director of AI Research Yann LeCun. LeCun noted that a majority of existing chatbots are still scripted by people and that it is going to take a while before humans can have real, rich conversations with their devices. Though Pereira agrees that we still have a while before we program our chatbot as a favorite in our phones, he points out that Google’s search engine progress is a step in the right direction, which includes less scripting and more machine learning.

Dr. Fernando Pereira explains why chatbot scripts form the foundation for the machine learning process and how Google’s search engine is enabling machines to understand context and content in new ways.

Pereira went on to describe how the words in our commands to existing chatbots are interpreted by the machine. He explained that there’s a sequence of events that occurs behind the scenes as the virtual assistant searches for an answer to your question. Essentially, every word that you speak is connected to information that the machine uses to piece together a representation of what you are asking.

A couple examples Pereira used to explain how he and his team train machines include collecting massive amounts of user input, basically anytime someone says “OK, Google,” and identifying the variation of verbal commands used to ask for the same thing.

Dr. Fernando Pereira explains how linking similar user errors allows our AI-powered chatbots to improve its ability to understand.

Pereira explains that the end goal is to enable machines to “do his bidding.” He was candid that the latest and greatest machine learning technology is not equipped with the language understanding to complete complex tasks only using our voice commands, like transferring money between your bank accounts or engaging in meaningful conversation. Though he’s uncertain of the timeline for when a human-level performing bot will hit the commercial market, he’s certain that coding is not the answer. He does not believe that programming is a viable solution to scale and appease an entire world of users. The future, in his eyes, is a machine that can continuously learn its users unique preferences through every interaction, while at the same time pulling from the knowledge that exists in the world to solve it. Until that day comes, he’ll have to continue to do his own bidding.

Dr. Fernando Pereira thinks we should be able to tell our virtual assistants exactly what we want, when we want it.

“The Understanding Computer: Google VP and Engineering Fellow Dr. Fernando Pereira in Conversation with Museum Historian John Markoff,” October 10, 2017. Produced by CHM Live.

The CHM Live team caught up with Dr. Fernando Pereira backstage to chat firsts and favorites. Here’s what he shared.

CHM Live: What is one piece of technology you can’t live without?

Fernando Pereira: Lightweight waterproof, breathable fabrics to keep me dry and warm in the mountains.

CHM Live: What is the first thing you do in the morning?

Fernando Pereira: Brew a double espresso from Zombie Runner beans.

CHM Live: What’s your favorite book?

Fernando Pereira: Fiction: Robert Musil’s The Man Without Qualities, which taught me more about the tragic emergence of modernity than any history book. Nonfiction: The Plausibility of Life: Resolving Darwin’s Dilemma, by John Gerhart and Marc Kirschner, which is taught me how feedback control and modularity are at the core of the evolution of complex organisms.

CHM Live: What’s on your playlist?

Fernando Pereira: I’m one of those dinosaurs who listens to full albums in lossless formats almost exclusively. Here’s some of what I’ve been listening to recently: “Blue Maqams,” Anouar Brahem; “Far From Over,” Vijay Iyer Sextet; “Voces de Sefarad,” Romina Basso & Alberto Mesirca; “Chamber Music,” Ballaké Sissoko & Vincent Segal; “Bartók: Klavierkonzerte 1-3” Géza Anda/Ferenc Fricsay (a favorite since college); “Kaija Saariaho: Chamber Works for Strings, vos. 2” Meta4/Pia Freund; “The Wind,” Kayhan Kalhor.

CHM Live: What’s the best part of your job?

Fernando Pereira: Building amazing teams to work on real, challenging AI problems that I never get tired of.

CHM Live: What did you want to be when you grew up?

Fernando Pereira: A scientist or engineer always. I was interested in space exploration from early in elementary school, then got interested in geology (still a significant interest) and electronics (built a lot of audio gear in my teens). Pure math grabbed me seriously to the point of considering doing it for graduate school, but computing and AI had the upper-hand from the time I wrote my first significant programs, in Algol 60, for a part-time job in college.

CHM Live: What’s your favorite piece of advice?

Fernando Pereira: My favorite advice for life and work comes from decades of climbing (smallish) mountains to ski them: A route is much easier when you know someone has already climbed it. Keep putting one foot in front of the other. Set a turn-around time and stick to it. Know where you are at all times. Question your guide if their actions don’t make sense. Impatience kills. All of these, and more, helped me not just to survive and enjoy the mountains, but to work and live better.

CHM Live: What was your first computer?

Fernando Pereira: First computer I programmed seriously: NCR-Elliott 4100 (1970). First personal computer: Apple Macintosh 128K (1985). Favorite computer architecture ever: DEC PDP-10.

CHM Live: Are you a MAC or PC user? iPhone or Android? Firefox or Chrome?

Fernando Pereira: Mac. Android. Chrome.

CHM Live: What’s the best concert you ever attended?

Fernando Pereira: Not the best acoustically—venue and amplification were pretty terrible for jazz—but the most thrilling and biggest influence in my later musical interests was Cascais Jazz in 1971, with bands led by Miles Davis, Ornette Coleman, Dizzy Gillespie, Dexter Gordon, and Phil Woods, with an incredible collection of sidemen including Keith Jarrett, Charlie Haden, Ed Blackwell, Dewey Redman, Thelonious Monk, Sonny Stitt, and Art Blakey.

CHM Live: Have you ever Googled yourself? What surprised you in the results?

Fernando Pereira: My first-last name combination is pretty common in Portugal, Brasil, and elsewhere. For a while in the early 2000s, the top search result for that name was an FBI most-wanted, which was pointed out to me by a famous academic who I had been competing with to hire an up-and-coming machine learning researcher.