There’s a persistent notion that Silicon Valley and the federal government are not compatible, leading some historians to argue that this very conflict was the cause of the Valley’s early success (read more).

Today, workers at the world’s largest technology companies such as Apple and Google have protested against federal contracts while private and public organizations continue to fall victim to sophisticated cyber attacks. These actions beg the question: If Silicon Valley and the federal government improve their relationship, could we create a better future?

If anyone could answer that question—and draw up a plan of action—it would be Steve Blank, the Father of Modern Entrepreneurship. He makes a case for the military industrial roots of Silicon Valley in a popular presentation called The Secret History of Silicon Valley, which he spoke about at CHM in 2008. And, as he reveals in his recent oral history for the Museum, Blank himself lives that intertwined history.

Steve Blank’s advice to aspiring entrepreneurs and a key part of the Lean Startup methodology

A latchkey kid with an absent father growing up in Queens, NY, Blank found refuge in the public library, a safe haven where he could pursue his interest in science and nurture a skill for assimilating lots of data. He’d always thought of himself as “kind of the dumb kid” but test results earned him a college scholarship. Accidentally applying to Michigan State University instead of the University of Michigan, he left home for the first time.

Blank admits he couldn’t have cared less about school and had no idea why he was going to college. He dropped out and hitchhiked to Florida where he got a job converting cargo planes to transport racehorses and discovered a deep interest in aviation electronics. That interest, and the insight that he needed discipline and a framework for his life, led him to join the Air Force in 1972, during the Vietnam War. He says, “The military both gave me structure and the ability to focus, but in a war zone it gave me the ability to discover what my real talents were, and that was a real surprise for everybody.” Those talents manifested not only in electronics but also . . . pranks.

Steve Blank describes pulling a prank to “turn off gravity” as a young Air Force recruit.

After leaving the Air Force and attending the University of Michigan on the GI bill, where his work study involved building the SCRAM system for their nuclear reactor out of a design from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. He says, “I always had nightmares whether I wired it incorrectly or not.” Blank worked for an automobile company in the Midwest, and it was for that job that he traveled to Silicon Valley for the first time in 1978. There, he was blown away by the energy of the region’s booming economy and excited by the pages and pages of want ads for scientists and engineers. The allure of California’s technology hub was so strong, he made the move to the West Coast and began a job at a startup called ESL.

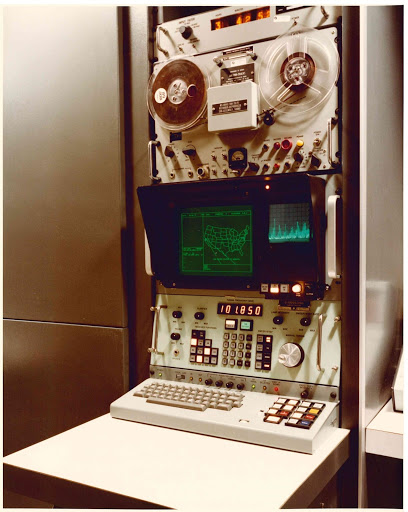

ESL was founded by a mathematician named Bill Perry, who later became secretary of defense under President Bill Clinton. ESL was responsible for the first application of computers in military intelligence in the US, and perhaps the world, Blank says. The company’s innovative intelligence receivers played an important role in the United States’ “offset strategy” against the Soviet Union, which ultimately won the Cold War (read more).

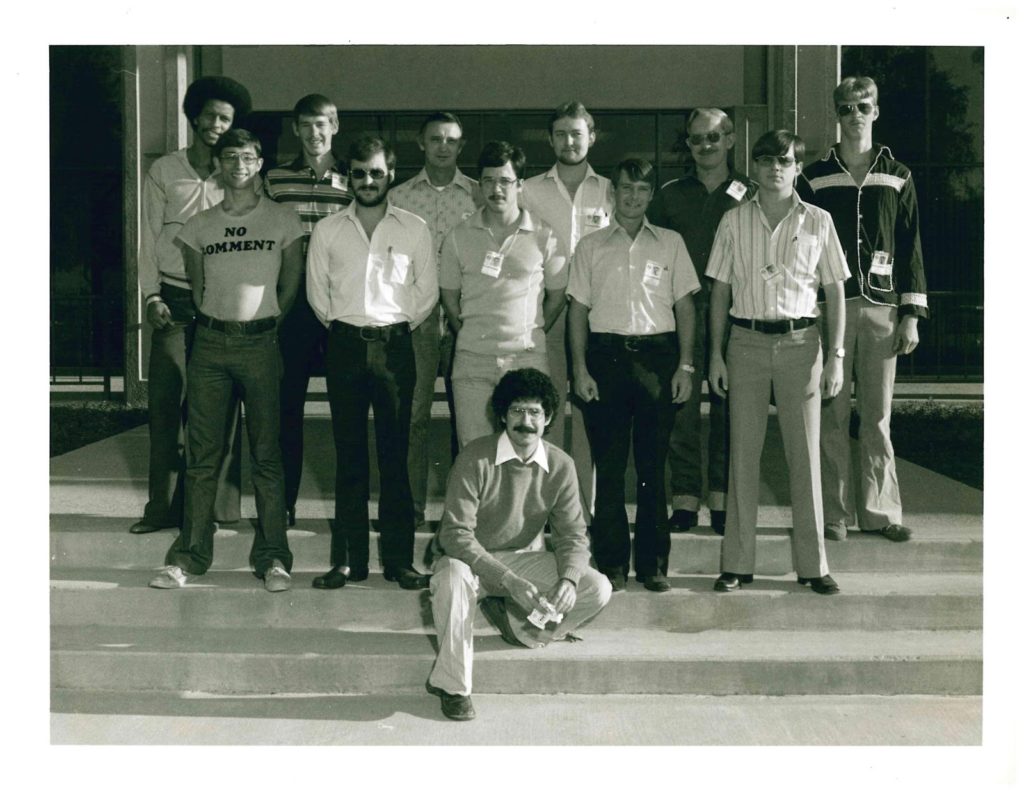

As the result of a hiring glitch, Blank ended up developing and delivering maintenance training for Guardrail, a complex communications and intelligence-gathering system for the Army. He says: “...so here I am developing course material. I never developed course material in my life, but I do remember taking courses in the military from what I thought were some of the best vocational trainers in the world, and I remembered how I liked to learn, so I put together a course on how I would like to be taught.”

Guardrail maintenance team; Steve Blank is seated in front (catalog number: 102792059)

Guardrail terminal (catalog number: 102792060)

The effort was a success. At ESL, Blank moved from a training instructor to “kind of a test engineer.” He was excited to be working with cutting-edge technology that was much more advanced than anything in the commercial world at that time. While in Australia with a top-secret project, he had an experience that made clear to him that “that [in] the commercial world and the black world, that is the classified world, the Venn diagram was almost nonexistent.” While the general public benefited from the work of companies that helped the government combat the Soviets, people often didn’t know about it. Blank witnessed the clash of those worldviews firsthand and it was a disconcerting experience.

Steve Blank tells a moving story about a coworker’s wife learning that her husband was doing top-secret work for the government.

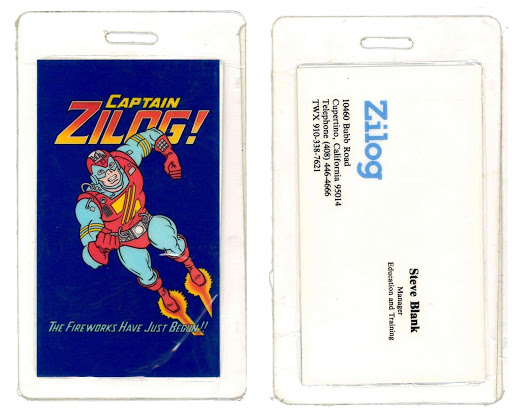

By now, Blank was working two jobs, at ESL and at Zilog, a microprocessor startup. The work took an unanticipated toll on him, he explains. One day in a meeting, Blank cracked a joke using a NATO codename for a punchline. No one laughed. Surprised, he looked around and realized he was not at ESL, as he’d thought, but at Zilog. Juggling the two jobs made him so tired that he did not remember traveling from one to the other that day. For the sake of his health and happiness, it was time to choose.

Blank realized that although his project at ESL was critical in the Cold War, and the advanced technology and access to the US president’s daily intelligence brief was incredibly seductive, he would never have any influence over what got built. “But these things called startups, there were no rules, and no rules was my middle name,” he says. He chose Zilog, the first of a series of eight startups in which he served in executive roles and as a cofounder in a variety of sectors, including microprocessors, biotech, gaming, and software.

Steve Blank’s Zilog employee badge (catalog number: 102792061)

Throughout his career, Blank was processing his experiences and identifying the key ideas behind what became the “Lean Startup model,” which he created, wrote about in a blog and books, and taught in courses he created at Berkeley, Stanford, and other universities. Blank explains that the Lean Startup “favors experimentation over elaborate planning, customer feedback over intuition, and iterative design over traditional ‘big design up front’ development.”

Steve Blank explains his startup model to nonprofits at CHM in 2019

When the National Science Foundation approached Blank and asked him to adapt his Lean LaunchPad course to guide the commercialization of publicly funded technology advances, he accepted—and launched the NSF Innovation Corps—now the standard for how scientific research is commercialized in the US.

Steve Blank talks about launching the NSF Innovation Corps.

Nine years after launching the Innovation Corps for NSF, thousands of scientists and engineers across a number of government agencies have been trained in the Lean Startup methodology, including the departments of Energy and Defense. For the latter, Blank co-created Hacking for Defense, a university course in which student teams use modern entrepreneurial tools and processes to solve real-world national security problems at startup speed. Today, 30 universities across the country teach the course and some have adapted the curriculum to other fields, including diplomacy, energy, nonprofits, oceans, and even public service.

There are some troublesome trends in Silicon Valley these days, Blank believes, caused in large part by the crippling of various regulatory bodies over the last few decades. He equates companies like Facebook and Twitter with monopolistic corporate giants of the past like Standard Oil in the days of the Robber Barons because of the severe negative social consequences for democracy. “I think calling Google and Facebook a startup just does injustice to the word startup. These are large corporate mega-whatever, as big as any corporation in the United States, but that are completely unregulated and out of control and are damaging our country,” Blank says. He believes there’s a reckoning coming and people will someday regret those names on their résumés.

What’s a potential solution? Blank would like to see the next generation of young people—including tech workers—consider public service. Reflecting on his time in the military, he says, “If there was any other form of service where if I had been an 18-year-old who had to give a year to work with other people from other parts of the country seeing things I didn’t know, I think it would have not only made me a better person, it would have been great for our country.”

His ongoing commitment to helping big government succeed, Blank attributes to the influence of Michael Krzys, who he met on his first day at college, and who would serve as the best man at his wedding. Michael had a magnetic personality and, as Blank says, “From the day he showed up in college had a profound belief that he wanted to do public service, and that he was going to dedicate his career to make other people’s lives better.” Michael died in a car crash at a young age, leaving behind his wife and children, and at least one friend who shared his belief that “to preserve and protect the values that make life worth living” is work worth doing.

NOTE: The last quote above is from Steve Blank’s 2019 Commencement Address at UC Santa Cruz.

The video clips featured in this article are highlights from Steve Blank’s CHM oral history interview. Follow the links below to hear more of Blank’s story:

OH Part 1: Blank describes his early life as a latchkey kid in Queens, New York; his service in the Air Force during the Vietnam War; and his work for ESL, Zilog and Convergent Technologies.

OH Part 2: Blank recalls lessons from his career as a marketing executive and serial entrepreneur at several important startups in the ’80s and ’90s, including MIPS, Ardent, Pixar, SuperMac and Rocket Science Games.

OH Part 3: Blank discusses the founding and rapid growth of his most successful startup, Epiphany; his formulation of the Lean Startup movement; his role as an author, adjunct professor and mentor to entrepreneurs; and his work to develop curriculum for the National Science Foundation’s I-Corps program.

Check out Steve's blog for additional stories and lessons learned.

Want more content like this? Subscribe to CHM.