Strolling around the Computer History Museum, there are exhibits that are immediately recognizable. All we need is a glimpse of the Altair 8800 or Apple I, and we just… know. We walk over and stand in front of these pieces, instinctively lowering our voices and giving a quiet nod to anyone nearby. Like noticing the chisel marks on a marble statue or the brushstrokes on an oil painting, we’re struck by the realization that what we’re seeing is the result of human imagination and ingenuity. What was once abstract and almost mythical is there right in front of us.

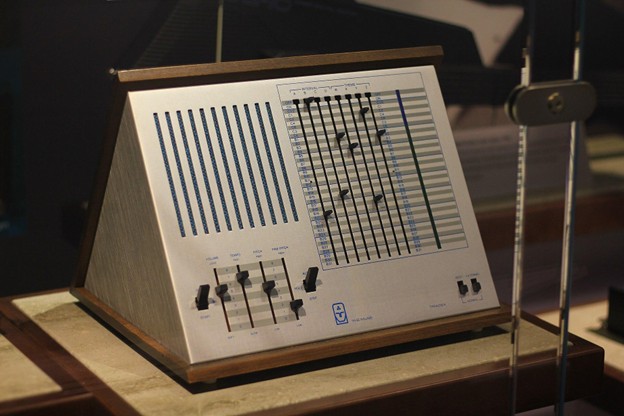

However, there are also items on display at the Computer History Museum whose significance isn’t immediately apparent. Take the Triadex Muse. You might mistake this wedge of metal, switches, and wood panels for an obsolete piece of stereo equipment or a Cold War-era intercom.

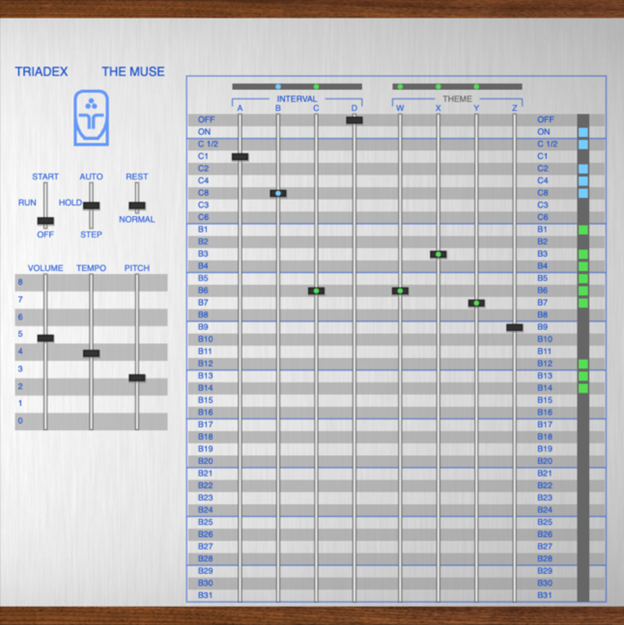

The Triadex Muse on display at the Computer History Museum. Photo by Michael Hicks, November 3, 2013. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

While it looks like something you’d find on some forgotten warehouse shelf, the Triadex Muse is an important piece of electronic music history. Developed by Edward Fredkin and Marvin Minsky at MIT in 1969, and commercially released in the early 1970s, it was the first algorithm-based sequencer/synthesizer intended for home consumers. It’s estimated that there were only 280 – 300 produced, making it a rare piece of gear.

You won’t find a friendly and familiar set of piano keys. The only controls are an orderly series of sliders. Its industrial design has more in common with that of a home appliance than a musical instrument. Like some sort of mystical radio receiver, beckoning users to adjust its controls until they land on some strange and alien wavelength.

The beauty of the Triadex Muse is in its simplicity. There’s no memory, no CPU, and no firmware. Just integrated circuits and electricity. Unlike the 1959 IBM 7090 mainframe computer, which was fed programming instructions via paper punch cards in coaxing out such party hits like Frère Jacques on the 1962 album Music from Mathematics, the only user input here is positioning sliders and flipping a couple switches.

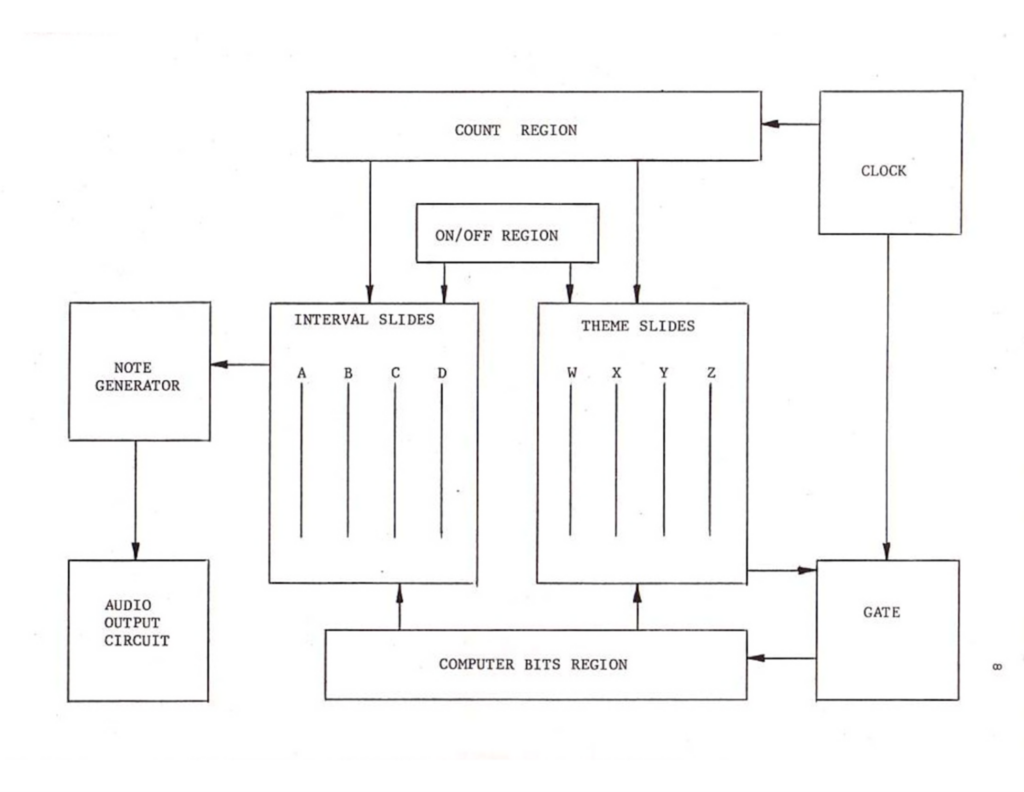

The Triadex Muse is a simple combination of electronics, lacking RAM, ROM, or software. (Source: Internet Archive)

If you were to randomly move the sliders to different positions and fire up the Triadex Muse, you’d likely hear the chirp of a square wave melody from its internal speaker and see a vertical band of blue and green lights twinkling in time. You might think that the Triadex Muse is like a modern step sequencer or drum machine. Orderly and predictable. This is 1972. Forget it.

You wouldn’t be wrong that the blinking lights correspond to a beat. At each tick of the Muse’s internal clock, this single column of lights shows the complete state of zeroes and ones. The Muse is essentially a 40 x 8 matrix, with zeroes and ones evaluated at each “tick” of its internal clock, triggering sounds, and with each state potentially changing what happens next.

While anyone with a background in computer science would know what these lamps represent, the average home consumer would have no idea. These glittering lights further add to its sense of mystery. Although you do get some control over the Muse’s output, you can’t play it like a regular instrument. Even the owner’s manual admits that, “The Muse isn’t a music box.” Depending on how you set the sliders, it’s unlikely you’re going to come up with a tune you can hum along with while you wash the dishes.

Triadex Muse improvisation. Courtesy of Adachi Tomomi.

While the Muse may sound like a robotic run-on sentence, it speaks in the familiar language of musical intervals.

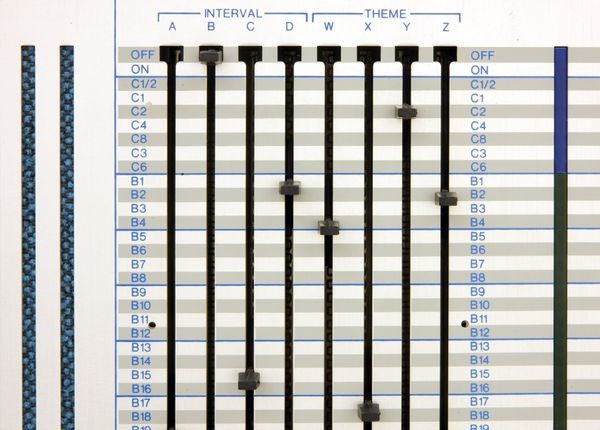

Closeup of the Triadex Muse showing intervals. Photo by Mark Richards.

The INTERVAL block has four sliders that select notes from the major scale. The positions of A, B, and C determine the pitch, while D adds an octave. There are no flatted thirds or minor scales. You can't play the blues. Though you might want to if you once owned the Triadex Muse and look up how much they’re currently going for—$$$.

The four INTERVAL switches, like much of the Muse, are deceptively straightforward. You might flip several to the same row and think you’ll hear a chord. Once again the Muse doesn’t follow modern conventions.

The Muse isn’t polyphonic. There is no harmony or overtones. This is binary arithmetic. Each interval is a weighted four-digit binary number. When summed they generate a 4-bit number that determines a new pitch. Music from mathematics… indeed.

The Muse’s intervals are triggered when the positions that they’re set to get a one bit from either the C or B section.

If you were to stare at the blue lights marked C ½ to C6 long enough, along with your friends asking you if you were feeling okay, you’d notice that they follow a set pattern. And if you knew how to count in binary (and let’s face it we know there are some of you out there), you’d see that the lamps C1, C2, C4, and C8 form a four-bit counter, cycling from 1 (0001) to 15 (1111) in a continuous loop. C ½ is simply the clock itself, a square wave that turns on and off at a rate linked to the tempo. C3 and C6 form a separate two-bit counter that increments every three cycles. By setting groups of threes against fours adds variety to the sequence.

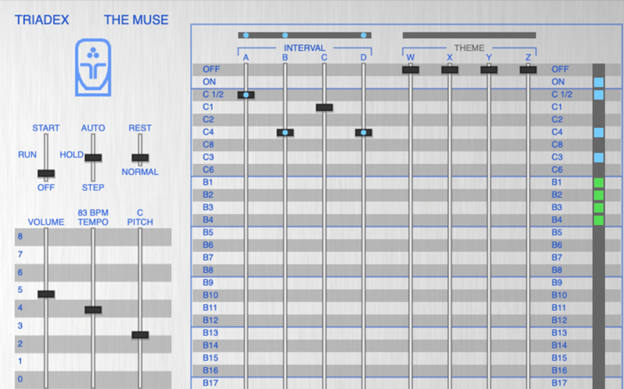

Counting up from C8, we see 0100, which is four in binary. (Source: JavaScript Triadex Muse emulator built by Donald Tillman)

In most instances, if you set the INTERVALS only to C positions, you’d get repeating patterns of tones about as musically exciting as the 1978 memory game Simon (no offense to Simon, which you can also see on display at the CHM).

The B region is where the Muse becomes more than a repeating blooper of bleeps, but a generator of pseudo-random chaos. You might observe the flickering green lights occupying B1 – B31, and just when you’ve identified a pattern, the sequence feeds back and morphs into something new.

To understand what’s happening, first you need to know what the four THEME sliders actually do. If you think that flipping these will give you a familiar musical preset like rock, jazz, or a rumba, the Muse once again betrays you.

Each THEME slider is technically a “tap.” A tap is like a tiny beacon, monitoring the binary state of a specific point in the C or B region, and sending that off to an XNOR logic gate.

I know. This sounds complex. But understanding the B register is like finding the answer to a riddle. Once you see it, it’s oh-so-obvious.

At every click, the XNOR (Exclusive NOR) logic gate makes a decision based on what it receives from the taps. If the gate receives an even number of ones (including all zeroes), it sends a one to B1. If the number of ones is odd, it sends a zero to B1. In its default state, B1 – B31 will be a band of green.

Every decision the Muse makes lurches forward, sometimes syncing up as the same conditions persist, and then suddenly shifting when the inputs change. B1 – B31 is what is known as a Linear Shift Register, an ever-evolving bucket brigade of bits, where a new zero or one is handed to the top, while the bottom bit falls out.

The 31-bit B register creates an almost unending variety of variations and patterns. (Source: Donald Tillman’s JavaScript based Triadex Muse emulator)

The Triadex Muse is a dead-end in the history of electronic music. While one could daisy chain it to other Muses, it used a proprietary I/O. There are no control voltages you could patch into modular synthesizers. And MIDI was a decade away. Its entire ecosystem was The Triadex Muse itself, an external speaker, and if the march of blue and green squares wasn’t enough visual stimulation, you could also buy a light unit with Gaussian-like blurs of psychedelic colors flowing with the beat.

Like DNA from extinct species whose fragments persist in modern organisms, the Muse’s influence lives on in algorithmic composition.

In a 2001 interview, Sean Booth of Autechre, pioneers of generative electronic music said about their process that, “There’s absolutely nothing random about what we do. There might be a lot of number crunching going on, but there’s nothing random in there.”

This is exactly what the Muse was doing in 1972.

Marvin Minsky, the co-creator of the Muse, said in his 1981 paper “Music, Mind, and Meaning” that the challenge of composing music is that, “Whatever the intent, control is required or novelty will turn to nonsense.” This philosophy is hardwired into the Muse.

The melodies of the Muse could sound familiar. Or even strange. But its output still sounds like music, with underlying rules and logic that our brains detect as patterns, even though the Muse makes it almost impossible to predict what it will play next.