Traditional Norwegian wedding party

Whether you’re a Maasai tribesman buying and selling cattle on your mobile phone, or a Norwegian bride to the altar with the groom you met online, it’s hard to think of an area of modern life that’s not being radically changed by the Web, the Internet, and mobile data. It is also hard to think of a field where even the wilder hyperbole about its importance has more chance of turning out to be true.

When it comes to making the history of the online world relevant to a museum audience, this is the good news. The bad news is that the complex, mercurial reaches of cyberspace are some of the most difficult subjects to pin down and display.

There are two main problems. First, the online world is insubstantial, and often more of a process than a thing. Trying to exhibit it in a museum context can remind you of the old quote about music criticism, above.

Second, it’s complicated. The same wide-reaching impacts that make cyberspace important also mean that it has lots of moving parts. Even its simplest stories can quickly involve different technologies, and geographies, and unfamiliar concepts. You often need to provide a lot of context and “backstories” just to make them intelligible.

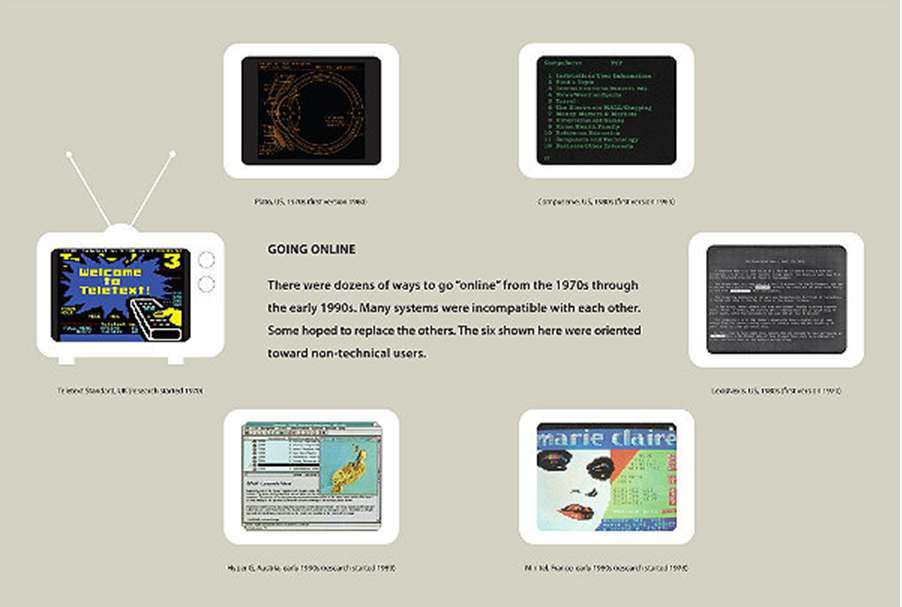

A further wrinkle is that many people barely realize the online world has a history at all. Very few know that the Web and Internet had both predecessors and serious competitors, or that those other systems have potential lessons to teach us. Those lessons go far beyond computing and touch on the most basic ways we share, navigate, and create knowledge.

At the Computer History Museum, we grappled with all of the issues above when we developed our permanent “Revolution” exhibition for early 2011. Taken together the “Networking and the Web” and “Mobile Computing” galleries, which I curated, form the first comprehensive exhibit on the origins of the online world. The parallel Web version of “Revolution” has all the same content plus more. Today, we’re continuing to refine our palette of techniques with exhibits on subjects from surrogate travel to the social impact of software.

The online world that absorbs our time and energy, fills now-online newspapers, and makes or breaks regional economies is actually quite insubstantial. If an observer from the past were to land in our time, he or she would be struck by how many people were staring into glowing, flickering, changing rectangles. Some of them are hand-sized, like your smartphone. Others sit on desks or stands, or even cover walls. In the future, personal ones may be constantly suspended on the edge of our vision in head‐up displays like Google Glass. The Onion satirized this modern reality with “Report: 90% Of Waking Hours Spent Staring At Glowing Rectangles.”

These playable games from the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s are a popular interactive at the CHM.

Alas, it’s not always so straightforward when it comes to complex online systems, whether Gopher or Minitel. Even if the original software exists and can be run reliably, there’s a big potential obstacle: Learning! Games are literally designed to be fun. They’re also designed to be quick and easy to get started, however hard to master.

Online systems are different. You may remember your early ventures into cyberspace through the glow of nostalgia. Or perhaps with mild disdain for what now seems like rudimentary technology. But either way, it’s easy to forget the hours and the false steps it took your newbie self to get comfortable on the Web, or CompuServe, or whatever.

Navigating a new piece of software can be work, even if it’s interesting.

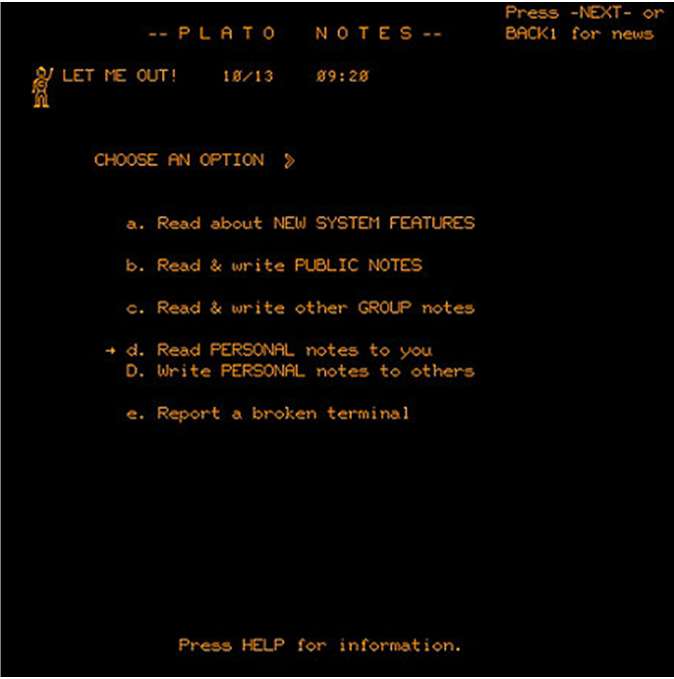

Three years ago the Museum helped host a spectacular multi-day commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the PLATO online system. As part of it the people at the PLATO History Foundation lovingly assembled a collection of PLATO terminals from several eras, connected to a working reenactment of the system. For original members of this close-knit community it was clearly an important, even moving experience to login once again to the familiar orange screens. But I noticed that my feet weren’t pulling me toward the reenactment area where the terminals sat in front of low, comfortable chairs.

Plato Notes, email and discussion

I’d never used PLATO, and I was curious to know what it looked and felt like. But I realized I wasn’t looking forward to actually getting started. It felt like work, like a tutorial in an unfamiliar piece of software, which is precisely what it was.

It seemed like the kind of task to do at home or at my desk rather than in the middle of a conference. Now there were pioneers to meet, pictures to take, tasks waiting in my inbox. I eventually pushed myself, and spent quite a while playing with PLATO Notes and various educational modules. It was easy to use, and just as innovative as the old-timers said, and I’m glad I did it.

But I’ve been studying the online world since 1995. If a Web historian has to push himself, how much persistence will you get from the average visitor?

It is also hard to say whether my session of mostly poking around and figuring out the lay of the land gave me a real impression of what an experienced PLATO user would do online. Sometimes, it can make more sense to look over the shoulder of an experienced guide than try to improvise a self-guided tour.

So why not video where the expert goes, like a dashboard camera in cyberspace?

That’s what we did in the Web gallery, where visitors can watch Web pioneer Kevin Hughes demo and explain a variety of key sites in “Surfing the Web in the Early 1990s”.

At this personal video station, Web and graphics pioneer Kevin Hughes takes visitors on a guided tour of key early Web sites.

It’s also how we show the pioneering 1978 Aspen Movie Map in our temporary exhibit on the history of “surrogate travel” and Google Maps with Street View.

This original early 1980s videotape shows a narrated demo of the pioneering Aspen Move Map, which offered many of the features of Google Earth with Street View.

A common rule of thumb with live interactives is that they have less than 30 seconds to “hook” the visitor. If the hook works, you have perhaps another three minutes for the whole interaction. Many video games make the cut. Surfing simple and appealing Web sites can also work.

Liquid Galaxy display, lobby. Visitors can take guided tours of Silicon Valley history (eBay pictured), or freely roam with Google Earth.

But for complex online environments, visitors do often benefit from a guided tour. You can even mix and match. For instance, the structured portion of this Google Earth interactive let’s users choose guided tours of historic Silicon Valley, from the HP garage to Netscape. But once at those places, they’re free to roam on their own.

The rules change for the Web version of exhibits. Here the visitor is usually sitting somewhere quiet and comfortable, rather than slogging through a gallery with finite energy and time. As we discover stable emulations we link to them from the Web version of “Revolution,” which has everything in the physical version plus more. In my view, online is where people will best explore ancient online environments, and discover the many webs before the Web at their own pace.

Of course, only a few historic systems have emulations. Most systems, if they still exist at all, require original hardware. This has its own issues; old computer equipment is often fragile, rare, and needs ongoing maintenance and training.

PDP-1 restoration room, demonstration

The result is that such setups are easiest to use intermittently. Examples include special events, such as the PLATO commemoration, and scheduled events like this weekly demonstration of a restored PDP-1. Fairs and specialty events are a perfect venue for running restorations; visitors are less hurried than in a typical exhibit, and the people running the old machines can focus their efforts in a concentrated window of time.

These 1970s Galaxy games are still going strong at CHM.

Arcade computer games are again an exception. These were meant to be played by thousands in an unsupervised environment… and can go for decades.

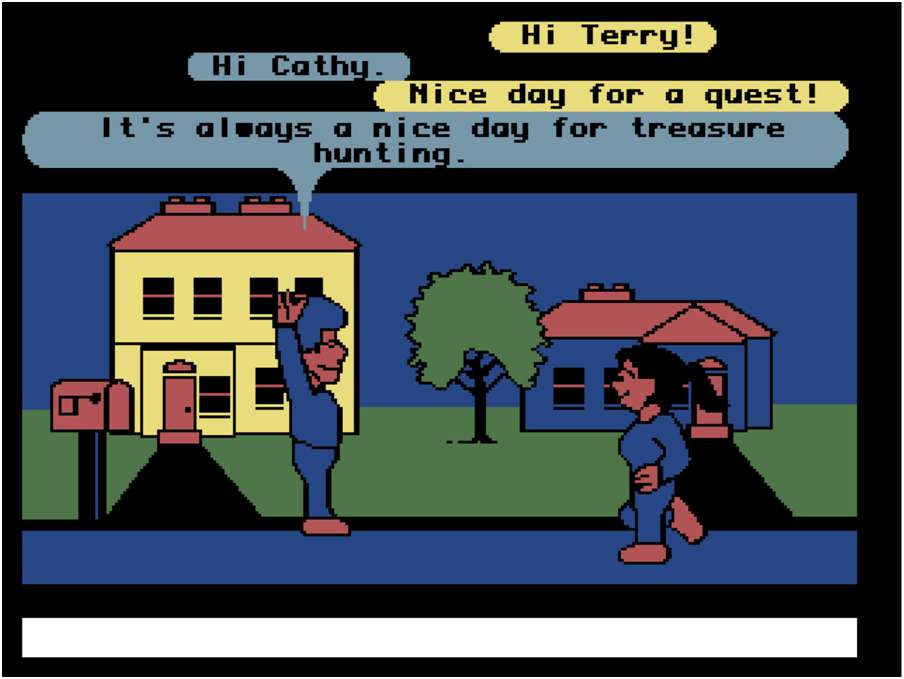

Another obstacle to direct re-creations of online systems is social interaction. A standalone early Web site or Minitel site is meaningful without other users. But a 1980s chat session or virtual world, or a modern twitter feed, is less so. Re-creating such systems is like trying to freeze and reproduce the back and forth of a live, group conversation.

Lucasfilm Habitat, online community

For social online systems like virtual worlds, some researchers have essentially given up on preserving the system itself. For them, video has become a standard way to capture their look and feel not just for exhibits, but for preservation. As the Web returns to the more social models and user-generated content that marked many of its predecessors, it can face similar issues.

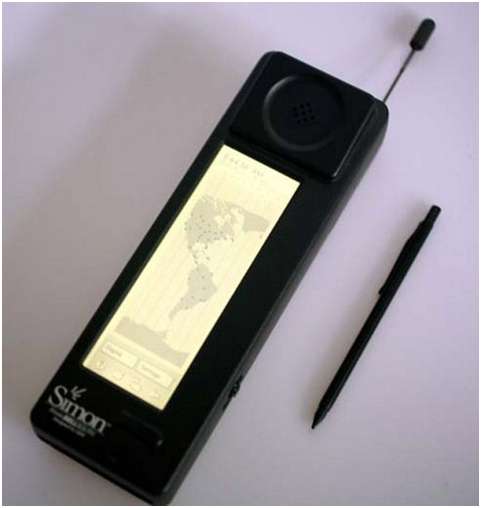

Mobile devices are relatively bright spots when it comes to exhibitability. BellSouth Simon, first smartphone, 1993.

Objects vary a lot in their natural exhibitability, to use an awkward-sounding term. It’s a bit like Maslow’s hierarchy of needs in reverse, running from the personal and visual to the dry and abstract. At the appealing end might be art, which is made to be interesting, personal objects like jewelry and clothing, and representations of the human figure. Items linked to sex and violence score high, from flint daggers to lingerie. Anything associated with vehicles seems to fascinate. Then come the rest, down to things like ordinary documents and the sorts of anonymous enclosures that house “back end” computer equipment.

One fairly rich vein of “exhibitability” is mobile computing, whose later history veers almost completely online. The little computers get much of the same design treatment, and human connection, as other poignant personal objects. Though in one sense they are just more life support systems for “glowing rectangles”, mobile computers are far more different from each other than are most PCs.

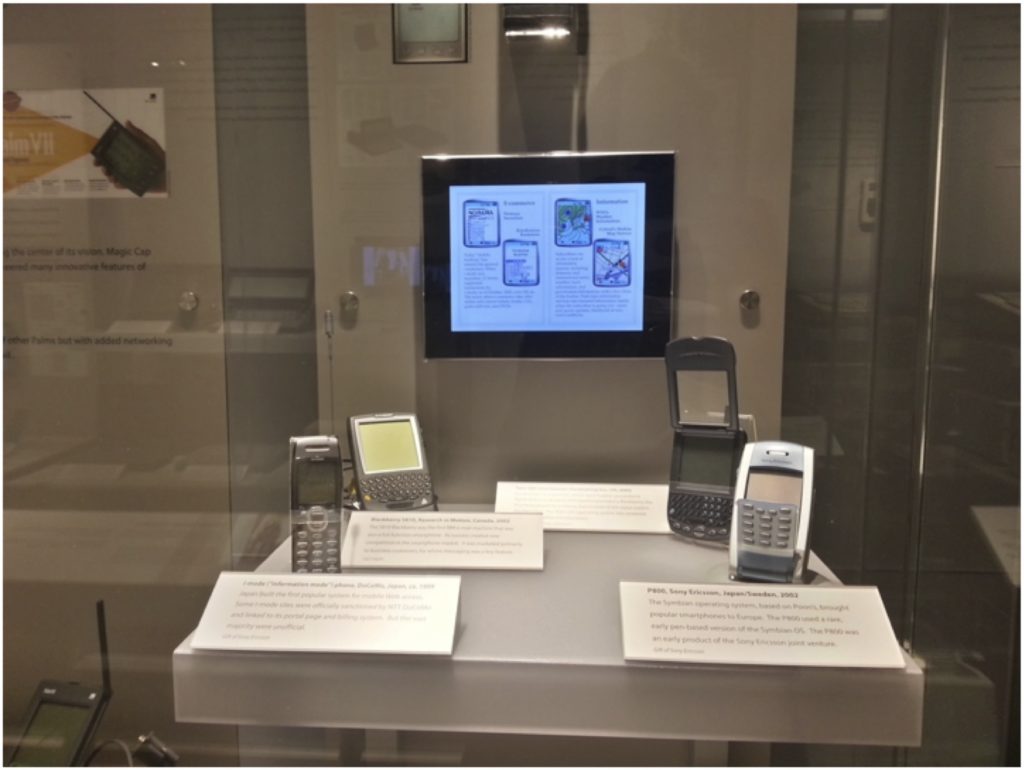

The thorniest question with the items in the Mobile Computing gallery was how to show off their little rectangles, the screens with the actual software that makes them go. No option is perfect. Leaving out the screens would be like showing half the device, especially with smartphones and handhelds where the software is completely integrated. Mocking up the screen in place would look fake, the way smartphones are displayed today at stores with no budget for live demo models. The compromise we reached was to show screenshots – or old ads with screenshots – in a rotating picture frame behind a cluster of machines.

Screenshots of the software from the physical objects are shown on video screens.

Smartphones with screenshots in a rotating picture frame. Pictured are i-Mode screens from Japan.

There is a final frontier, a place where the last crutch of easily exhibitable items gets kicked away. Behind the glowing screens that while away our hours lies an enormous infrastructure. It runs out from our home Ethernet routers and spans the globe with wires, server farms, undersea cables, and radio towers. The recent book Tubes by Andrew Blum (Ecco, 2012) explores this physical structure of the online world.

But even though there’s so much stuff, millions of tons of equipment power-hungry enough to suck down two percent of the world’s electricity, there’s a problem when it comes to putting it on display. Much of it looks the same, and has for decades. Even removing a front panel often just reveals standardized circuit boards. It can sometimes be hard to tell from a glance whether a given set of featureless cabinets in a windowless back room are for computer networking or telephone systems. The sorts of miniature models of giant installations that work so well in science museums for, say, electricity generating stations or copper mines could be awfully uniform if applied to the stuff behind the Web.

You can see gears move on a steam engine, or a Babbage engine. Even the old electromechanical telephone switches are impressively intricate and physical. But you can’t see electrons move over a network. The action, the variety, the magic that eventually brings our screens to life is all on the inside, invisible. Also barely visible are the marks of the bitter, decades-long standards wars that form much of the history of networking.

Had ARCNET won the battle to wire the office instead of Ethernet, the only obvious difference might be a different shape of connector in the back of your machine. Had the French CYCLADES network become the standard for connecting networks to each other, instead of Internet protocols, there might be no visible difference at all. But the economics of the online world, the balance of power over standards, and in some cases what you can and can’t do on your glowing screens could be quite different.

So how can you explain the origins of “plumbing” layers like the Internet where bits get moved around – but there may not even be any friendly screens or human interface to show? In short, how do you display a standard?

In the Networking gallery, we did of course show particularly meaningful or typical examples of the kinds of behind-the-scenes equipment that makes the online world go. We’ve got a fridge-sized IMP from the original ARPAnet; a Cisco router; a dish antenna; a Google server rack, and so on. But one or two of each major class of equipment is usually enough.

A portion of the Networking gallery in “Revolution.” Packet-switching video in foreground; refrigerator-sized ARPAnet IMP behind.

Beyond that, exhibiting a networking design like packet switching or a standard like Ethernet is kind of like displaying the wind. It’s invisible, but its effects can still be seen. This is the rarified realm of exhibits on other abstract topics, from math to cellular respiration. You show their effects through people, objects, interactives, and other things that do have a clear exhibitability. If you choose well, these indirect objects can even act as bait.

When creating an exhibit you also have the luxury of hindsight. So those visible “effects” don’t necessarily have to follow chronology. For instance, we start the “Networking” gallery with a common grounding theme throughout the exhibition; tracing the old roots of the subject to be explored. Here this takes the form of an interactive telegraph key. Visitors can tap out their initials, and feel under their fingers the staccato manifestation of the 200 year old “big idea” that underpins nearly everything in the gallery and the Museum: Transporting information over electrified wires. Over the centuries the wires have shrunk too small to see, and the switches have gone from something that filled your hand to millions per square inch. But the principle is the same, from Morse keys to ENIAC to the iPhone.

The Networking gallery briefly luxuriates in the gorgeous polished brass and delicate visible gears of equipment from the first wired world, that of 19th century telecommunication. It also shows early modems and a teletype. But then it tells the rest of the story with an increasing palette of indirect techniques.

Photogenic 19th century telecommunications equipment, Networking and the Web gallery, “Revolution”.

Photogenic 19th century telecommunications equipment, Networking and the Web gallery, “Revolution”.

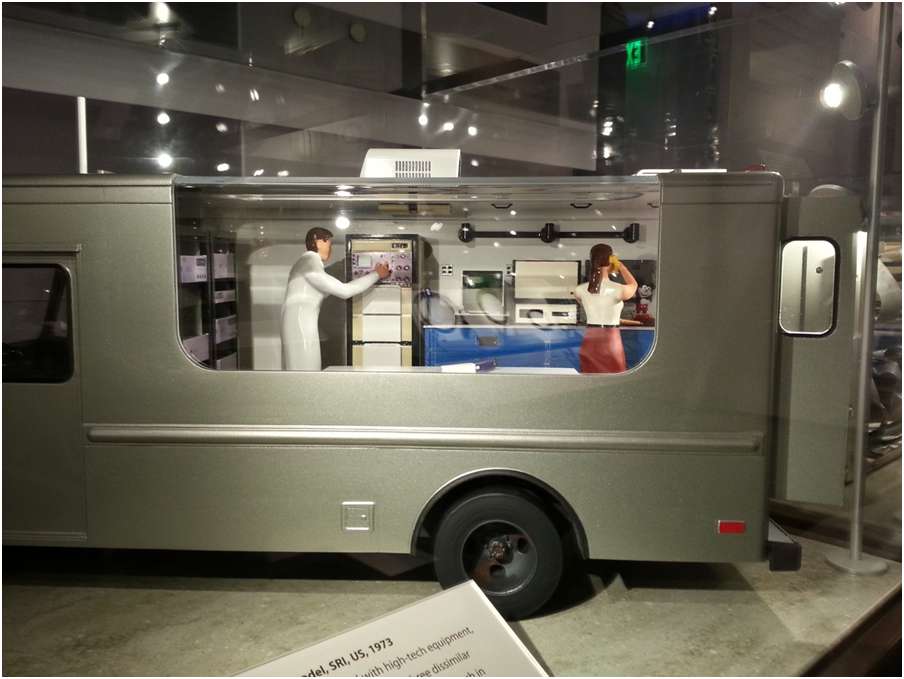

The principles of packet switching get covered in an animated movie. Pictures and stories about people – from the colorful networking and personal computing legend Bob Taylor, to Al Gore – literally flesh out the conflicts and ideas that drove the effort to tie computers together into a world-spanning net. Internet protocols are represented by a lovely scale model of the research van where they were first fully tested. The real van is under a cover in back of the museum. Books, t-shirts, and reprints of newspaper articles come in to illustrate particular points. A variety of network connectors show some of the few visible manifestations of the bitter, costly standards wars that raged through the 1970s and ‘80s.

Two thirds of the stories in our upcoming exhibit on game-changing software cover the online world. They’ll draw on and extend the techniques we’ve used in “Revolution.” But the structure of the new exhibit will highlight another technique in itself: the case study. By going in-depth with seven real-world examples, from Wikipedia to iTunes to World of Warcraft, the exhibit will flesh out the sometimes insubstantial tendrils of cyberspace with specific stories, and people, and impacts on their lives.

Computers started as calculating machines made from spare parts of the then-century-old telecommunications industry. They were later converted into communications and knowledge devices. A century from now, they may be seen as part of a larger stream of the history of technology for dealing with information. But today they still straddle worlds. This creates tensions when it comes to practical exhibits. Is the online world part of computing, or of the history of books and sharing information, or of telecommunication? All solutions are compromises.

The online world doesn’t appear out of thin air. Its glowing rectangles are attached to computers, and those computers to networking equipment. But how much to exhibit these physical “support systems” for cyberspace within an exhibit on the online world can depend on context. Is the online exhibit standalone, or is it part of a bigger exhibit on computers, or communications, or something else?

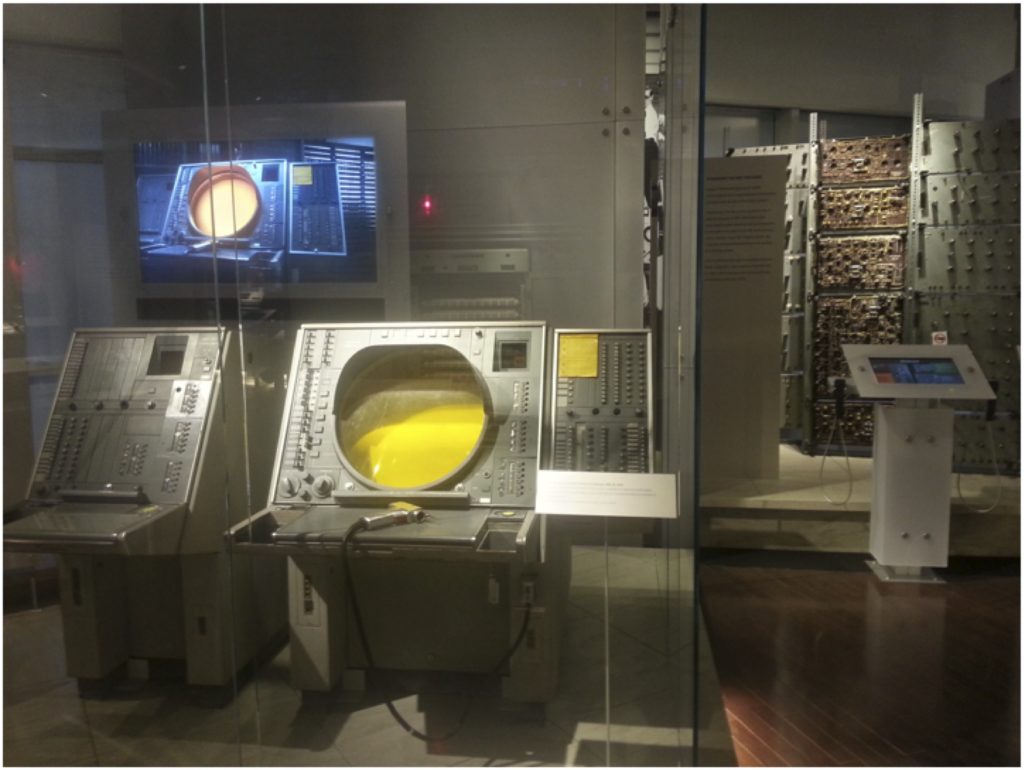

Just a support system for going online? SAGE terminal, Real Time Computing gallery, “Revolution”.

As I’ve mentioned, much networking equipment is short on exhibitability. Computers themselves, though, can push some hot buttons. Yet the stories that make these computers interesting often have little to do with any online roles. For instance, the story of early Apples is animated by the rivalry between Jobs and Gates, and the funkily home-built nature of early PCs. The SAGE system was a milestone for networking, with 23 centers connected in the 1950s. But it was equally important for interactive computing, and use of a pointing device, and military computing, and more. Using such computers in a pure cyberspace exhibit can potentially shortchange their other roles. But putting them in other galleries reduces the stock of interesting online objects.

We put SAGE in the “Real-Time Computing” gallery, and the Apples are with PCs. Both are referred to in Networking and the Web. But it’s an imperfect compromise, especially in the physical exhibit where there’s no convenient way to cross-link.

“Who was online?” panel conceptually groups a number of disparate systems and explores who used them. Networking and the Web, “Revolution”.

The fact that people are mostly ignorant about the real origins of the online world is a double-edged sword. It makes it easy to offer enticing revelations as “hooks”. For instance, that the Web was originally meant to be as participatory as a giant Wikipedia. Or, that social networking features go back to the 1960s. But it also means that exhibits need huge amounts of backstory and framing context for each section. This adds to both the size of any display and to possible information overload for visitors.

Both effects are intensified by another factor. Most visitors have no preconceptions at all about, say, the origins of analog computers or disk drives. But the Web and Internet are so much a part of modern life that nearly everybody seems to recall a few bits and pieces about their origins; often wrong.

Here are some examples of facts that can be confusing.

For many the Web and the Internet blend together in a kind of cyber mush. People have little practical reason to care that they are actually two completely different levels of the online world. The Web is an online information system running over the “plumbing” provided by the underlying network – in this case the Internet. They’re as different from each other as TV sets from the shows that play on them, or programs from operating systems.

Unfortunately, making this complex distinction is key to the narrative arc of the gallery, since each level has its own very distinct history. In fact, how we approached it could determine the gallery’s physical design in a substantial way.

We went back and forth with possible solutions. Should we try to tell both stories in a single gallery – or have two completely separate galleries, “Networking” and “The Web”? Or compromise, and have two separate “tracks” within a single gallery?

In the end we used the two-track approach for the physical exhibition; you turn left for networking and right for the Web. But we created two completely separate galleries for the Web version, partly because there’s no clear way to have separate but associated “tracks” online.

“Walled Gardens” panel conceptually groups a number of 1970s and ‘80s online systems. Networking and the Web, “Revolution”.

Most visitors – including some computing professionals – have little idea that there were Web-like systems before the Web, or other ways of connecting computers (and computer networks) to each other than the Internet. Without this key fact, tracing the origins of cyberspace is a bit like trying to present the history of World War I to an audience that doesn’t realize there was more than one side.

The cycle of invention followed by spread and then ruthless winnowing is a repeating theme in technology. Throughout our exhibits we present not just the winning standard or company, but also at least a representative sampling of the losers and minor players. Visitors get this immediately in areas where the fights are well- remembered, like the “Personal Computers” gallery. But it takes more explanation for cyberspace.

From e-commerce to chat to social networking and user-generated content, most of the features we use on the Web today were already being used by tens of millions in the 1980s on earlier online systems. Online systems from the 1960s through the ‘80s were a great example of William Gibson’s observation that: “The future is already here; it’s just not evenly distributed.”

But not all these “revelations” require heavy lifting. A number are easily digested, gee-whiz facts that can surprise and occasionally delight visitors. For instance:

A wearable costume of PegMan from Google Maps with Street View stands guard over the front desk.

Showing online systems in a museum may be as paradoxical as music criticism or dancing about architecture, as I hinted with the quote at the start of this paper. That doesn’t prevent us from trying to do it well.

But there’s a problem that no single exhibit can address. I’m talking about the societal “blind spot” around the very existence, and importance, of the rich history that produced the online world. People readily see the history of books and printing as crucial to understanding the Enlightenment, and the rise of science, and much of what makes our world. But the beginnings of online knowledge get pigeonholed as something niche, and techie, and off to the side.

To change the preconceptions with which visitors approach this pivotal history will take time, and continued efforts to put it on display. But it will also take continued efforts to create its place in relevant academic disciplines from History, to Internet Studies, to Computer Science, to Sociology, to ones we cannot yet name.

This blog piece started as a blog piece, was turned into a paper for the conference at the London Science Museum "Making the History of Computing Relevant," to be published by Springer later this year; got presented at that conference as a talk, and has now been converted back into a blog piece.