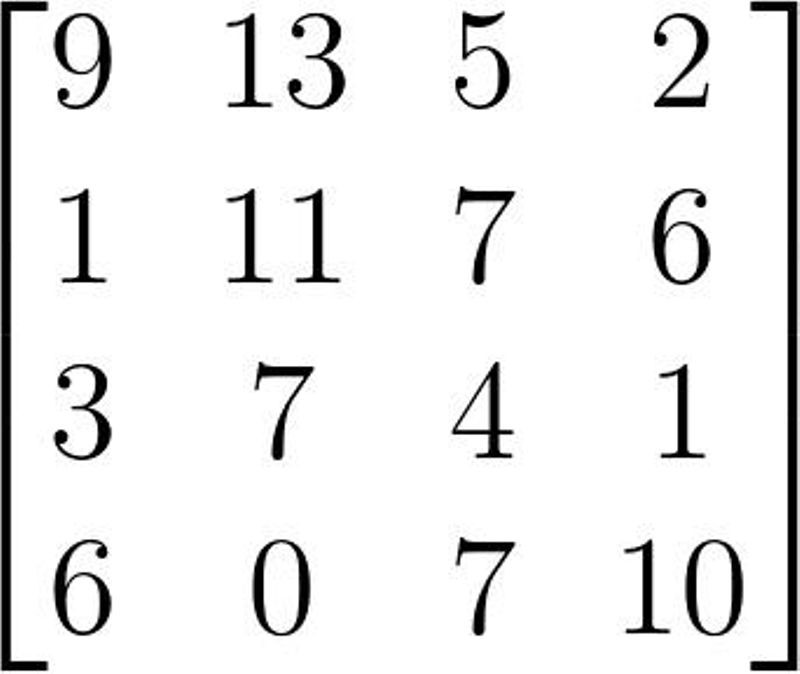

Typical matrix.

Though thousands of years old, mathematics underwent dramatic changes in the 20th century with the development of the electronic computer. New techniques and approaches to solving mathematical problems, as well as the re-imagining of older methods for use on computers, have been the underpinnings for the technical progress defining our age: atomic bombs, hearing aids, television, jet travel, bridge design, genetics, stock market prices, space travel — all underpinned by modern mathematics.

Across dozens of such scientific and technical fields, wherever we are measuring change over time it’s possible to arrange the resulting numerical quantities in matrix form. (A matrix is just a rectangular array of numbers or symbols arranged in rows and columns). It turns out that using matrices is an excellent way of solving all sorts of scientific and engineering problems.

This year CHM honors American mathematician and inventor of the MATLAB numerical computing environment, Cleve Moler. Moler created the original MATLAB program, short for “Matrix Laboratory,” while at the University of New Mexico as a quick calculator for his students doing basic matrix operations.

Today MATLAB is no longer a single program but a platform and an ecosystem used by millions of scientists and engineers around the world. Its maker, MathWorks, has 4,000 employees in two dozen cities and Moler serves as Founder and Chief Mathematician at the company.

Cleve Moler and friend.

Cleve B. Moler was born in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1939 and was a precocious student.

When it came time to attend university, Moler chose Caltech over MIT (he was accepted at both) due its small size and mathematics because it offered the most electives.

Due to his success in John Todd’s courses in numerical analsysis, he chose that area in which to specialize and Moler began to write simple programs for solving his homework on Caltech’s Burroughs 205 Datatron computer, in 1959.

Burroughs B205 computer, UCLA, ca. 1959.

Upon graduating with a BA in mathematics in 1961, went to Stanford University to study under George Forsythe, a legendary figure there and founder of its computer science department. Forsythe and Todd had worked together earlier at UCLA’s Institute for Numerical Analysis at which the groundbreaking SWAC computer was installed. So Moler was studying with two of the leading figures in the field.

At Stanford, Moler wrote his 1965 dissertation on “Finite difference methods for the eigenvalues of Laplace’s operator” and so began his lifelong interest in matrices. After a postdoc year at the ETH in Zurich, Moler joined the faculty of mathematics at the University of Michigan in 1966. This began a 20-year academic career at Michigan, at the University of New Mexico, and with a couple of visits back to Stanford.

In the 1970s, Moler was a co-author of LINPACK and EISPACK, Fortran subroutine libraries for matrix computation. He wanted students to be able to access these packages without writing Fortran programs, so he wrote the first version of MATLAB as a simple, interactive matrix calculator. The system, both the mathematics and the array syntax, turned out to be useful in other fields of science and engineering that he had not anticipated. Moler made MATLAB freely available.

In 1984, with Moler’s permission Jack Little and Stev Bangert re-wrote and enhanced MATLAB, making it available on the new IBM PC, and Little and Moler founded MathWorks to commercialize the result.

Mathworks headquarters staff, 2007.

Little has remained with the company as CEO all this time, a rare occurrence, and Mathworks is now celebrating its 33rd anniversary. The dazzling variety of applications technical community has created using MATLAB – from space craft dynamics to derivatives trading — has made it a kind of universal moldeinng and calculation tool ideally suited to science and engineering problems. To paraphrase Galileo, today “The Book of Nature is written in MATLAB.”