Jim Williams at Linear Technology in 2006

Light, sound, temperature: the world is a symphony of vibrations. All around us is a world alive with continuously varying signals. These real world sensations are called anal og signals to distinguish them from digital signals–which can only switch between 0 and 1 (on and off) and which exist only in a computer. Many systems have both analog and digital elements: a smartphone, for example, has both analog and digital parts and converts signals back and forth between the two continuously. Over half of the iPhone 4 is composed of analog circuits or systems.

Capturing these real-world signals and making them do amazing things is the domain of the analog circuit designer. Jim Williams, who was considered one of the best analog circuit designers in the world, suffered a stroke and passed away on June 12, 2011. Linear Technology, the company Jim worked for, has loaned the Computer History Museum Jim’s unique workbench so that visitors can learn about Jim and the fascinating world of analog circuit design.

The practice of designing analog circuits and systems is as much art as science. Real world signals vary continuously and can be complex and sometimes unpredictable. Analog engineers must combine technical knowledge with a great deal of experience and intuition in order to harness them. Analog designers often work under a master engineer, such as Jim Williams, for many years to learn the secrets of good analog design. This long apprenticeship gives them a special status among other engineers who consider analog design to be a mysterious process. Williams himself did not consider it a mystery.

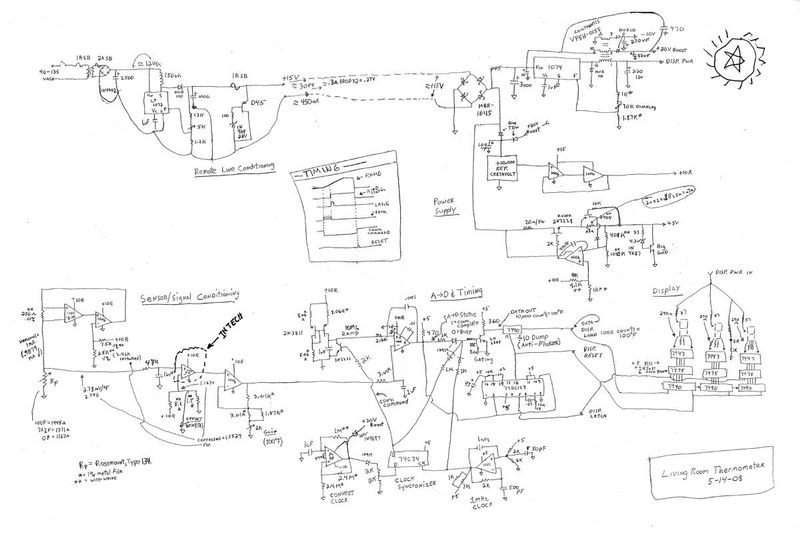

Jim Williams, “Living Room Thermometer” sculpture, 2008 Source: Fran Hoffart

In the analog world, Jim Williams was a rock star. His many articles and books encouraged a generation of engineers to pursue intuitive analog design, where experimentation and testing were emphasized over theory and math.

Jim grew up in Detroit and had a neighbor with electronics equipment that he found fascinating. He attended college but then dropped out after one term. He took a job at MIT as a lab technician building and repairing complex scientific equipment. While there he began teaching and writing, the start of a long career in making complicated topics understandable to other engineers.

Jim Williams “Living Room Thermometer” sketch or schematic diagram, 2008 Source: Jim Williams

Despite his fame, he was a humble man, helping anyone who asked. His love of electronics knew few bounds: his home laboratory was at least as good as the one at work and he designed and built beautiful working electronic sculptures in his spare time. Williams was entirely self-taught yet set the bar for the entire technical community.

Jim Williams enjoyed designing circuits that were complex but also beautiful. He often arranged the components in a dazzling way, creating functional works of art. This is a sketch of an analog circuit for a thermometer, which Williams made into a sculpture as shown in the photo.

Jim Williams at work at Linear Technology, 2004

The workspace of an analog engineer is a space where analog circuits are prototyped and tested. The arrangement of test equipment and materials is a highly personal choice and reflects the work style of the designer. Jim Williams’s desk, with its vintage test equipment and three decades of old analog circuit projects, reflects his many years of experience.

Jim Williams’s workbench at Linear Technology Corporation in Milpitas, California.

Workmates respected Jim’s privacy and would never dream of taking something from his workspace, in part fostered by Jim’s desire to make his workbench look as uninviting as possible. Williams never used a computer, even for email. He preferred talking to people directly. If his phone rang, he always answered it, regardless of who it was. Even if he was deep in thought, he was always approachable for help.

Analog circuit board prototype from Jim Williams’s desk

Analog designers build prototype circuit boards to test out their ideas. Designers begin by soldering assorted electrical components onto a blank circuit board. The components on many of Jim Willliams’s boards were un-mounted and hanging in the air, allowing him to build and test circuits very quickly.

After building a circuit board, the designer often uses an oscilloscope to visualize how the circuit is functioning. By building circuits, in contrast to simulating them on a computer in software, the designer is forced to confront the real world behavior of electrical signals that the software often misses.

Jim Williams wrote Application Notes, a series of technical documents that explain how to use analog integrated circuits created by Jim’s company Linear Technology. He often added amusing cartoons to the back page showing his playful side.