Just a few weeks ago, we received an interesting donation to the Museum: a commemorative punched card from the IBM Pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair. It’s a standard IBM punched card—a piece of card stock with holes (usually) punched into it to represent information. This one, however, was given to visitors to the IBM Pavilion who took part in an exhibit there on handwriting recognition and databases, or what an IBM brochure describing the fair called Optical Scanning and Information Retrieval. I’m just going to keep things easy and call it IBM’s This Date in History exhibit.

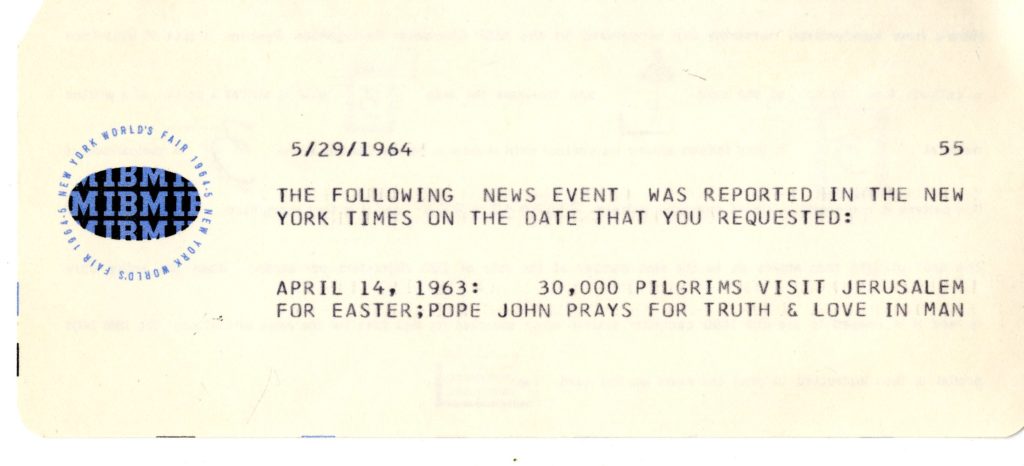

Here’s the front of the card:

IBM punched card memento, Gift of Glenn Lea, X7133.2014

As you can see, it has a special IBM World’s Fair logo on the left with the current date (5/29/1964) and a statement that reads: “The following news event was reported in the New York Times on the date that you requested.” This is followed by a date—which the visitor selects—and a news headline from that date.

The idea behind the card was to provide a keepsake record of one’s visit, and the experience was as follows: Visitors would write a date in history on a small card. The card was then fed into an “optical character reader” where the handwritten date was converted into digital form. In turn, this date information was fed into an IBM 1460 computer system. The computer would then look up a major news event from that date by accessing its database (stored on a disk drive) and print the result on the card. The answer was also flashed on a Times Square-style display at the exhibit. The news database came from the New York Times archive (hence all dates had to be post-1851, when the Times was founded).

Speaking of limits to dates, perhaps to show that even IBM could have a sense of humor, the exhibit and system programmers had predicted that sooner or later someone would enter a date in the future, just to try to stump the machine. In fact, it happened on the very first day of the fair and the commemorative card given to that visitor read: “The date you have requested was February 3, 1970. Since this date is still in the future, we will not have access to the events of this day for 2,133 days.”

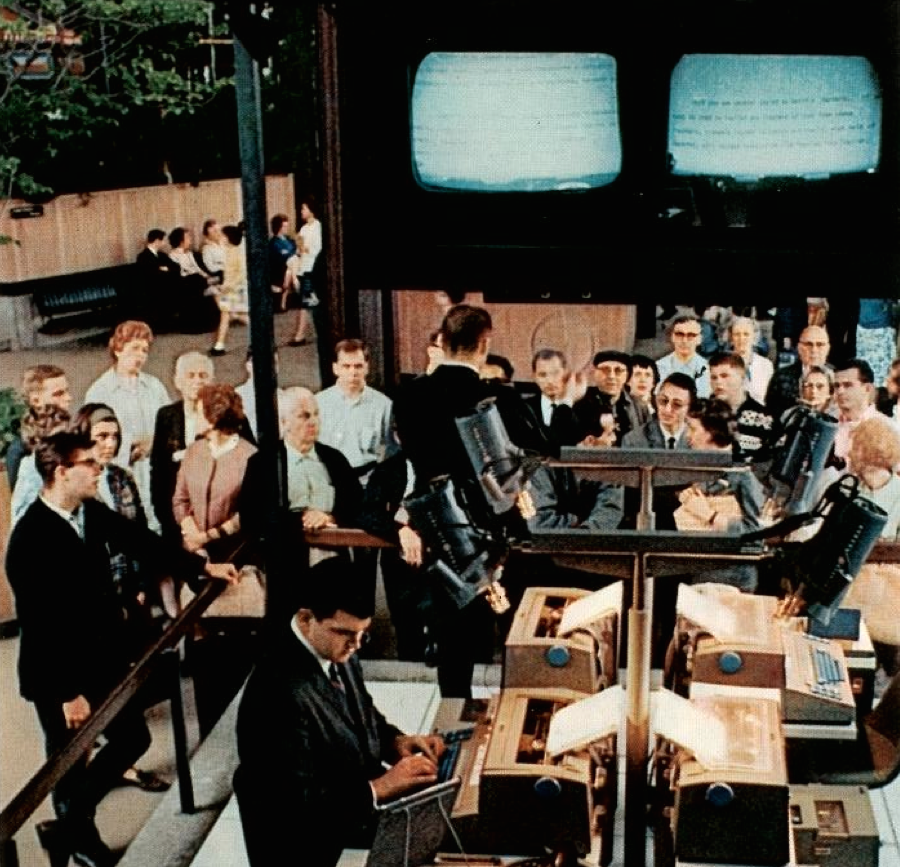

IBM employee interacting with fairgoers at the IBM This Date in History exhibit, 1964

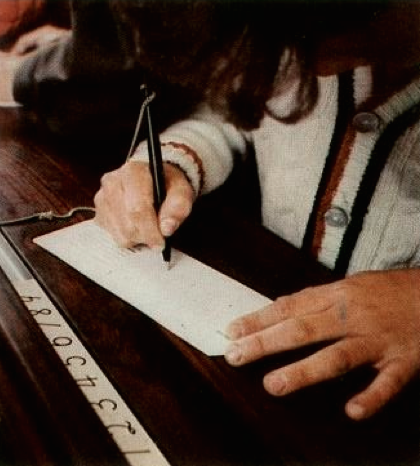

Visitor entering date on a card for the This Date in History exhibit.

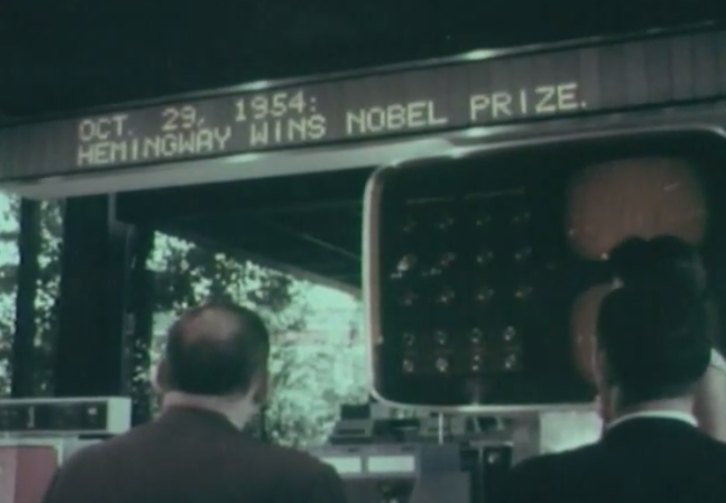

Still from Edwin Newmans’ report on the IBM This Date in History exhibit showing Times Square-style display of the result, 1964.

Edwin Newman, as part of an hour-long critique of the fair, gives an excellent, if brief, demonstration of the exhibit (from 0:08 to 1:02).

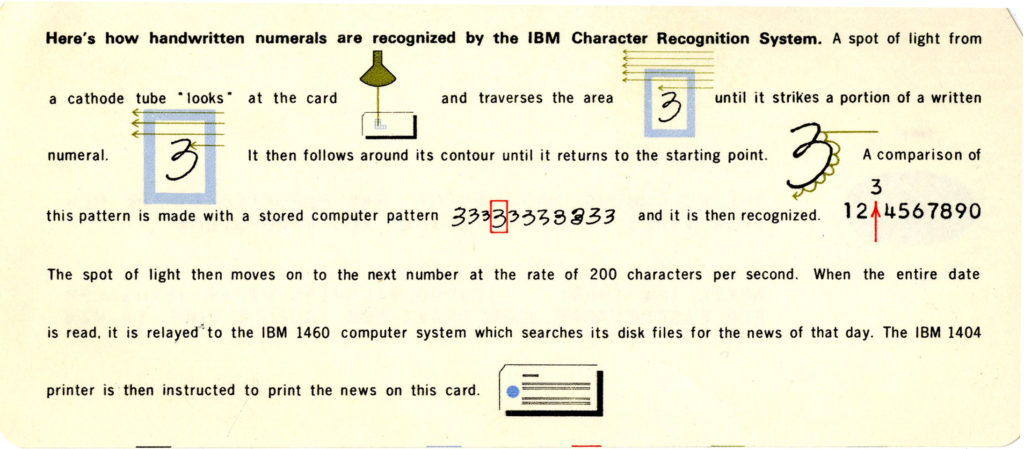

Let’s now take a look at the back of the card:

The back of a world's fair punch card, describing its number recognition system.

As we can see, the back of the commemorative card describes in quasi-pictorial form the whole process behind the exhibit.

The optical character recognition system from the exhibit is described in an IBM brochure as “experimental” and the reader may have noticed by now that it is limited to numbers only—dates were submitted in the form “3-9-1861.” Recognizing only numbers is a much simpler computational problem to solve. But behind this specific exhibit is a serious effort by IBM to develop its expertise in handwriting recognition more generally. Why? Because the then-current method of converting large amounts of handwritten information was “one of the slowest steps in automatic data processing.” Typically, in 1964, data was manually typed onto punched cards. The idea here was to cut out this step by using the computer itself to read human handwriting.

It’s interesting to note in this case that, from the perspective of 50 years on, it is we who have adopted data entry as a normal part of life in order to co-exist with computers while handwriting seems a lost art and hopelessly inefficient for record keeping. In fact, more modern computer systems based on handwriting recognition have a long and not-too-successful history, but the problem they are trying to solve was the same: how to get information into machine-readable form.

Using handwriting recognition in the 1964 exhibit was particularly smart of IBM because it is a natural means of communication for humans and isolates the visitor from direct exposure to the physical workings of the computer. Both are comforting to a visitor and increase the likelihood that they will be receptive to the experience and carry positive associations about computers and IBM home with them. Many people chose their birthdays as the date to look up.

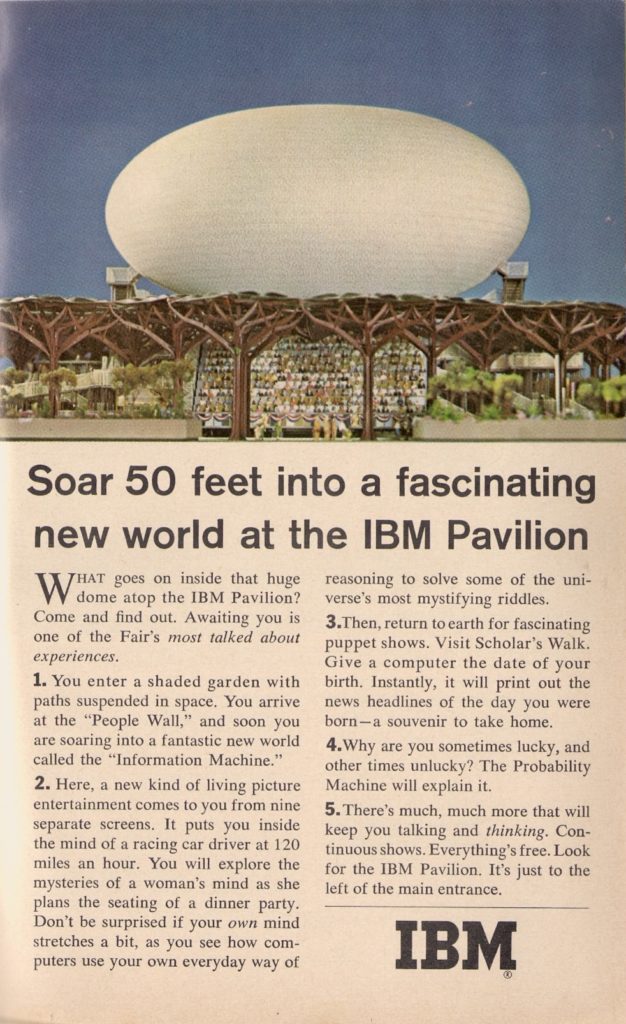

IBM had several other exhibits within its Eero Saarinen-designed ovoid building:

Russian-to-English machine translation exhibit at the IBM Pavilion.

Advertisement for the IBM Pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair, New York.

As IBM sought to increase demand for computers, it needed to take the general public along with for the ride. Its job was made easier by positive prevailing economic conditions and a desire within industry and business to “automate” (which meant computerize). But efforts like the 1964 World’s Fair were a longer-term bet: that by introducing computers in the informal festival-like atmosphere of a fair, the computer would be seen as force for positive change, rather than the popular notion of computers as mysterious and, possibly, dangerous. About 185,000 people a day visited the fair during its two-year run. For a great number of those people who visited the IBM Pavilion (the second most popular stop at the fair), it was their first direct interaction with a computer of any kind, a fact of great cultural significance and one which we celebrate today with this simple punched card memento.