Videos can be shared instantaneously from your computer or smart phone with just the push of a button.

The number one question I get asked about oral histories is: “When will the video be available online?” Not, will the video be available online, but when. With instant video sharing made possible by websites like YouTube and Vimeo, in addition to mobile apps like Vine, it’s no longer a question of capability, but of time.

The Computer History Museum’s Oral Histories Collection consists of both audio and video recordings from pioneers in the fields of computing and technology. To ensure the long-term preservation of these oral histories, in addition to providing easy public access to them, it has long been considered best practice to have recordings transcribed into a text document, also known as a transcript. The Museum is proud to provide access to transcripts of over four hundred of its approximately six hundred recordings. But in a day and age when video reigns supreme, is text the only way to go?

Because they are searchable, transcripts give researchers the ability to pick and choose the areas of an interview they would like to focus on and skim over areas that are perhaps not so relevant to their research. But with a recording, it can be cumbersome to find and focus on specific segments without watching or listening to the entire recording from start to finish, stopping to rewind, playing the recording back, and jotting down time markers of clips you want to return to. (Note that an oral history in the Museum’s collection can last anywhere from two to six hours and span over the course of several days!) So, compared to raw video or audio, transcripts are looking better all the time.

But there is a cost. By transcribing a media recording to text, you lose much of what is unique and special about a recording in the first place: the person. Think about it, would you rather read a transcript of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech or would you rather hear and see him deliver it? From facial expressions, emphasis placed on specific words, hand gestures, and laughter to what a person chooses to wear (if you’re Mark Zuckerberg you might opt for a t-shirt and “hoodie” rather than a suit and tie) to the recording location and physical surroundings—you lose these types of sensory elements when you refer only to a transcript. Text sacrifices the person in favor of transmitting information.

With the limitations of transcripts acknowledged, coupled with the progress of technology, many oral history programs have transitioned to showcasing video in addition to offering a transcript, including the Museum of Modern Art, the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, and the Regional Oral History Office, part of UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library.

With such wonderful precedents, I began making my own case for posting the Museum’s oral history videos on our website. Luckily, the idea was well received and I was met with enthusiasm and support from my amazing colleagues. But once I had the A-OK, the questions began filtering in. How were we going to do this? How were we going to make this work for the Museum? And maybe the most worrisome question of all—my own question—how was I, non-techie extraordinaire, going to make this happen?

In contrast to the positive aspects of video, I was also being reminded more and more that an audio or video recording is often unnecessary to a researcher, just more fat to cut through when only a few key pieces of information are needed. Secondly, we would have to involve an already overworked media team (thank you, Eric Dennis!) and a busy IT department to help design a new web interface (thank you, Anna Boyko!). And furthermore, video presents a challenge in terms of file size as it can take up a great deal of bandwidth on an institution’s website—one of the reasons the Museum has been reluctant to host video on its website in the past. (A couple of the examples I cited above have chosen to supplement a transcript with short video excerpts, which is another great way to give visitors and researchers the flavor of an interviewee without posting the entire video. Creating a YouTube channel, as the Museum has done to provide access to its live shows and historical videos, is also a fantastic way to share video.)

So, the plot thickens.

Video or text? Video in place of text? Video and text? YouTube or computerhistory.org? Excerpts or an entire oral history? If an entire oral history, how would you be able to easily find the information you need—you can’t search a video. The answer: an interactive transcript.

During my first summer at the Museum, I was introduced to a new video technology being used for MIT’s 150 Infinite History project by Senior Curator Dag Spicer. The technology was further championed by Chairman of the Board of Trustees Len Shustek along with Trustee and unwavering oral history program supporter Gardner Hendrie. MIT was using something called an interactive transcript that was created by a company called 3PlayMedia, started by and comprised of MIT Sloan School of Management graduates. It was awesome. The transcript was synchronized to the video, and the best part was that you could search by keyword because there was a transcript and because the video and transcript were aligned. What’s more is your YouTube account can be linked to 3PlayMedia, and videos can be directly uploaded from your YouTube channel for transcription. This is an especially fantastic option for the Museum because, rather than burdening computerhistory.org with large HD videos, oral history videos can be hosted on our YouTube channel and simply embedded on our website. Not to mention the interactive transcript’s toolbar enables social media sharing along with print and download options. Wouldn’t it be cool if we could do something like this, too?

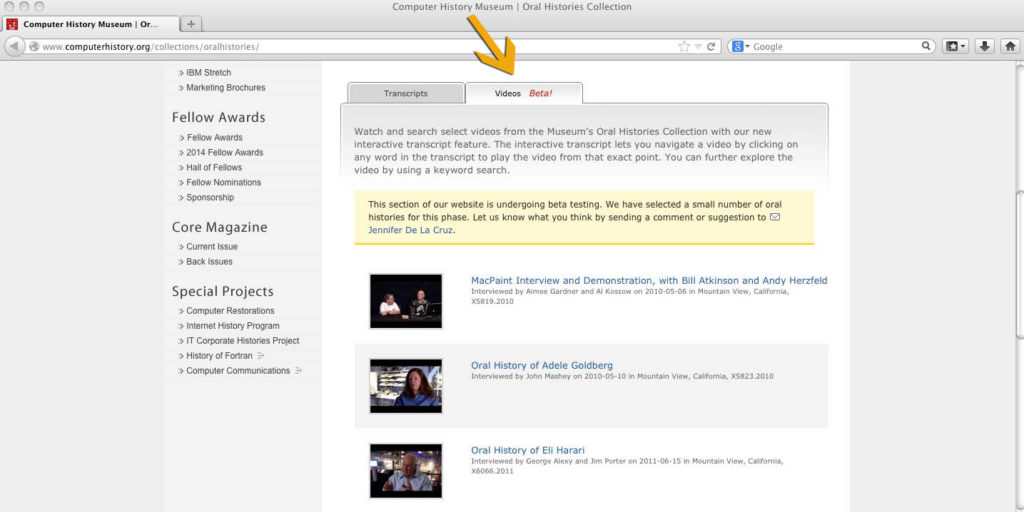

Select the Videos tab to check out our new experimental, interactive oral histories.

I’m happy to say we have! Check out our first test cases on the Oral Histories Collection page, including oral histories of software pioneer Adele Goldberg, flash memory innovator Eli Harari, and a panel on the development of MacPaint, just to name a few. Click on the Videos Beta! tab.

The interactive transcript feature adds a new dimension to our website and changes how visitors—the general public as well as researchers—can access and interact with our one-of-a-kind collection.

This is a new undertaking for the Museum and we are excited to see how this develops in 2014.