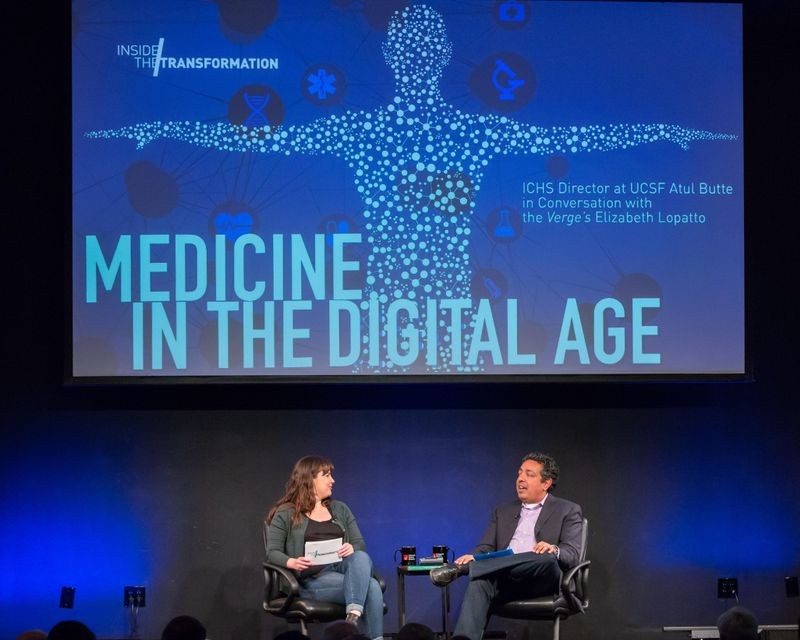

Today, sequencing our genetic code or doing a DNA test is affordable, fast, and can even connect people with long lost relatives (for example, Ancestry.com and 23andMe). Additionally, these genetic databases are producing real-world applications—including creating targeted drug therapies to treat certain cancers, narrowing down suspects in criminal investigations, and identifying disease-causing genetic mutations. On Wednesday May 23, the director of the Institute of Computational Health Sciences (ICHS) at UCSF Atul Butte joined the Verge’s Science Editor Elizabeth Lopatto at the Computer History Museum for a conversation about the ethical practices, privacy concerns, and technological innovation around genomics and precision medicine.

Butte began by establishing that the Human Genome Project, despite taking 13 years and costing three billion dollars, was one of the “magic moments” in the field of genomics. He explained that in 2003 as the Human Genome project wrapped up, it kick-started an arms race to create cost-effective DNA sequencing technologies. This pursuit of innovation by medical companies and researchers has clearly paid off—seeing that a person today can get their entire DNA sequenced for as cheap as $499, in as short as 26 hours, and on a plate that can fit in your pocket.

However, there are downsides to this kind of innovation. As more people add their DNA data to public databases, there’s a greater risk to consumer privacy. Lopatto brought up the controversial Golden State Killer case as an example of this concern, because police caught the alleged murderer by using DNA from the crime scenes and comparing it to DNA from a genealogy site. Butte acknowledged that having publicly available DNA databases is tricky because it’s a “give and take”—meaning people depend on others to upload, or “give,” their DNA data in order to get matched with family members. At the same time, people are losing their ability to block others from using, or “taking,” their DNA information. Despite the wide range of ethical and privacy concerns, the public generally seems to accept the risks that come along with signing up for these genetic services. Furthermore, Butte doesn’t see databases that store our personal information going away anytime soon.

The director of the Institute of Computational Health Sciences at UCSF Dr. Atul Butte discusses the trade-off between making your DNA available for genetic services, like Ancestry.com & 23AndMe, and keeping your genetic data private.

Next, Lopatto brought up an interesting way that DNA is being used in archaeology. Butte’s research team was recently involved in studying the DNA of a mummified Chilean girl. He explains that the reason he got involved with this controversial case was simple: it helped to build on the database he’s working on. The more DNA data that gets sequenced and stored, the better the computer will get at identifying specific genetic mutations connected to particular diseases, syndromes, and/or abnormalities. In the real world, this means the next time a patient shows up at a hospital with similar symptoms, they’ll have a better chance at matching the patient’s DNA to a mutation from a known disease in the database. As a doctor, being able to provide a diagnosis for a patient, especially to the parents in pediatric cases, Butte explained, can bring tremendous relief and, depending on the disease, treatment.

Dr. Atul Butte explains how powerful DNA data can be in diagnosing unexplained illnesses.

Then, the conversation turned to a discussion about the medical application of DNA with precision medicine. Butte gave a concrete example of this as treatments for cancers with specific DNA mutations—that is, patients with the same type of cancer (for example, breast cancer) without that specific DNA mutation wouldn’t benefit from that treatment. The effectiveness of these targeted drug therapies has created new ways for doctors to diagnose and treat diseases. Butte is clear that these revolutionary discoveries wouldn’t be possible without patient data. He admits that, although, they are “drowning” in the staggering amount of data that exists, there still isn’t enough. He clarified that it’s not just the sheer amount of data that matters, it’s also the type of data that gets recorded and collected. Butte explains that doctors need both your biological and nonbiological measurements to deliver healthcare in this precise customized way.

Dr. Atul Butte defines precision medicine and explains the type of data the medical community needs to deliver personalized healthcare.

Lopatto brought up the question about how to safeguard our private information in a field of medicine that runs solely on private health information. Butte points to the 1996 Health Insurance Portability Accountability Act (HIPPA) as the rulebook for safeguarding everyone’s data, adding that the medical community must continue the standard practice of using the data in a “safe, responsible, and respectful way.” He assured that if anyone needed to de-identify the data, there are ethics review boards and “lots of eyes” to ensure that our health data stays private. The consensus from his perspective is that the quantity of data is more important than knowing the actual person associated with it.

The precision medicine conversation continued as Butte highlighted a major problem, which is that doctors classify and code diseases similarly to the way they did over 100 years ago. The latest medical diagnostic code book, known as ICD-10, is not precise enough to communicate and tell the computer a patient’s specific diagnosis. Until the medical diagnostic code books adapt the codes in a way that the doctors can input the important characteristics of a disease, creating hyper-targeted treatments or discovering genetic mutations will become more difficult.

Dr. Atul Butte discusses why the traditional way of coding diagnosis from the ICD-10 book isn’t sufficient enough to keep up with the advancements in biomedical technology.

After Butte touched on several more topics—including the US CRISPR trial, understanding risk when reviewing DNA results, and the impact of the high-resolution megapixel cameras in decreasing sequencing time—the conversation concluded with some surprises he’s seen during his work in genetic medicine research. He’s impressed with the amount of public interest there is in DNA sequencing, proven by the growing number of people that are joining the millions of people already part of DNA databases. As medicine moves into the digital age, he hopes the enthusiasm to harness the power of big data in healthcare continues because the future of our health might depend on it.

Dr. Atul Butte shares a story about how he became a “quantified-self believer” after losing weight using digital health tracking devices. Butte says our current medical system isn’t equipped to handle the data from these devices and explains why that needs to change.

“Medicine in the Digital Age,” ICHS Director at UCSF Dr. Atul Butte in Conversation with the Verge’s Elizabeth Lopatto,” May 23, 2018 at the Computer History Museum. Produced by CHM Live.