Donald and Laura Lehmer. Courtesy of Severo Ornstein.

At the dawn of the modern computing era teenager Laura Lehmer Gould and her brother Donald Lehmer were the youngest “un-programmers.” That is because ENIAC, one of the world’s first general-purpose computers, was programmed with an array of switches and cables. When each program had been run, someone had to return the cables to their proper storage box to be available for the next program. Shortly after the installation of the ENIAC their parents, Derrick Henry Lehmer and Emma Trotskaya Lehmer, who were well-known number theorists at the University of California at Berkeley, were invited to use the machine for mathematical research.

Designed to aid the war effort and completed in 1945 at the Moore School of the University of Pennsylvania by John Mauchly and J. Presper Eckert, ENIAC, or Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer, was a pioneering electronic digital computer. However, it was not a stored-program computer in the modern sense of the term. Historian David Alan Grier described it as more like an array of electronic adding machines and arithmetic units that were held together by a web of large electrical cables.1

The machine itself, which was about one thousand times faster than the electro-mechanical calculators of that time, occupied a large room and was evocative of a telephone switchboard of the era, with a plugboard array that could be rewired with cables of different lengths.

That’s where Gould and her brother came in.

As youngsters they would accompany their parents on cross-country car trips to gather valuable research time on the machine. The ENIAC would be programmed with plugboard-style cables that were operated in the manner of a mechanical telephone switchboard. While traveling with their parents, a babysitter wasn’t always available, and so the two children who were then in their early teens, would accompany their parents for the long programming sessions that often stretched into the evening. After the programs ran, their job was to aid in resetting the computer by laboriously disconnected all of the cables and placing them in boxes according to length.

“It was our job to strike when the program was over and put all of the cables in their appropriate boxes sorted by lengths,” she recalled.2

Neither brother nor sister remember precisely what programs their parents were developing. It is possible that they were exploring different methods for predicting the next prime number, but it is also conceivable that they were involved in some aspect of classified military research.

The ENIAC had been commissioned to help the United States Army calculate artillery trajectories. However, Donald Lehmer noted that his father was a pacifist: “He had no interest in doing anything that would kill people. I suspect he was thinking about prime numbers.”

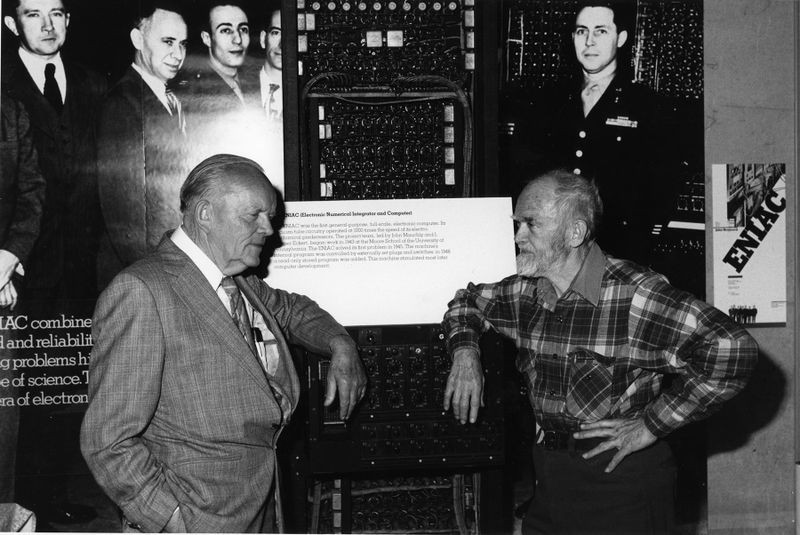

D. H. Lehmer (left) and Dick Clippinger (right) in front of ENIAC exhibit at The Computer Museum, Collection of the Computer History Museum, 102622619

Indeed, Dr. Lehmer briefly left the University of California during the height of the loyalty oath controversy to serve as the director of the National Bureau of Standards’ Institute for Numerical Analysis.

And indeed, the Lehmers had a long prior interest in building a computing device to speed up the problem of factoring. As early as 1930, they had proposed the idea of the design of an electric factoring machine to the Carnegie Institute of Technology.

They wrote: “[. . . ]To perform the operation with pencil and paper one must start with the million or so numbers among which the solution is known to lie. Actually to write out all these numbers is obviously impossible. [. . .] We therefore propose to construct a machine which will canvass a million numbers in about three minutes.”

The Lehmers’ son does have a clear memory of seeing a cloak-and-dagger operation at the ENIAC facility: “Things were kind of secret,” he recalled. “It could have been war activities. It seemed extremely clandestine. I remember going down a concrete staircase into a building. The doors were 20 feet high and 10 feet high. When we entered there was a big of rush of air as it was pressurized to keep the dirt out.”

He remembers that his parents would get access to the machine when it wasn’t running its official programs. He also has a clear memory of how painstaking it was to actually program the ENIAC.

“Now[a]days we load a program in a 10th of a second,” he said. “Then it took two or three days and then debugging. Once a program was running people were reluctant to give it up. They would post a guard and tell us, ‘don’t touch a thing.’”

Both children would go on to careers that were deeply influenced by computing. Laura became a linguist and would later work as a research scientist at Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center. Donald would go on to become an engineer.

Laura would marry Severo Ornstein, who was one of a small team of engineers led by Wesley Cark who built the LINC, which is thought to be the first true personal computer. Later Ornstein was also one of the designers of the Interface Message Processors for the original ARPANET.

What both of the teenagers remember most clearly from the era were the long multiday cross-country drives the Lehmer family would make each summer from Berkeley to the ENIAC facility. Like most extending family outings, the trips were not without stress.

Laura Gould remembers sharing the backseat with her brother, occasionally uneasily: “Every once in awhile my father would blow up and pull the car over to the side of the road and say, ‘alright now get out and fight!’ And we would.”

Read “Unprogramming the ENIAC: Lehmer Child’s Play” on Medium.