It may be hard to imagine in our current digital age, but printed books were once considered an innovative (and dangerous!) technology. And, for decades, books have helped people to understand the quickly evolving revolution in computing.

On January 20, 2026, author and UC Santa Barbara history professor W. Patrick McCray was on stage at CHM Live to share his experiences writing ReadMe: A Bookish History of Computing from Electronic Brains to Everything Machines (MIT Press, 2025). The fireside chat was moderated by David C. Brock, CHM's Robert and Bette Finnigan Fellow.

McCray began to think about his project during the pandemic, when he thought he might be able to write a book about books so that he could read at home and avoid traveling to archives. Those circumstances made him consider how every book has its own origin story and history, and McCray became just as interested in exploring the authors and their writing processes, their relationships with their publishers, and the cultural context of the books he was writing about as he was their content.

For ReadMe, McCray wanted to explore the ways technology was presented to the public. He limited his selection to nonfiction books that represented a range of different functions. Some, like Alvin Toffler’s Future Shock (1970), were bestsellers by any measure, some were technical textbooks, and others popularized computing for a general audience. He also had to choose his historical timeframe.

Patrick McCray explains the rationale for the books he selected.

Records really do matter, says McCray, noting that it’s critical that people donate their papers to a repository. He shared what he found in some of those archives.

McCray first discussed Giant Brains: Or, Machines That Think, published in 1949. The author, Edmund C. Berkeley, had worked in the booming insurance industry from the 1930s to ‘50s, a sector rich in data and among the major adopters of digital and electronic computers—called “giant brains” at the time.

Berkeley wanted to explain what computers were and how they worked and hired a writing coach to ensure that the average person could understand his book. Alarmed by post-WWII geopolitical tensions and the threat of nuclear war, Berkeley used the book to warn that computers were powerful tools that could be dangerous if not developed with robust ethics and morals.

MIT has a robust archival collection for Joseph Weizenbaum and his book Computer Power and Human Reason (1976), reported McCray. Weizenbaum was a computer scientist at MIT in the early 1960s famous for writing the program for the ELIZA chatbot that functioned as a Rogerian psychotherapist. Many users felt that ELIZA was interacting with them on an emotional level. Horrified to see how people imbued the program with empathy, Weizenbaum became concerned about what computers and computer scientists should and shouldn’t do. His book was a critique of the profession, and perhaps of himself.

Patrick McCray describes an author’s personal dilemma.

Ted Nelson’s 1974 Computer Lib/Dream Machines combined two books back-to-back, assembled and self-published by the author himself. It was a political manifesto that promoted computers as tools for personal liberation, freedom, and democracy. Nelson also predicted that people would someday have computers in their pockets and considered how they would interact with hypermedia and multimedia, like images, sound, and text. Reprinted in 1987, after the PC revolution had not unfolded the way he’d hoped, Nelson lamented that ubiquitous computers could oppress people from everywhere.

Don Knuth, author of the influential The Art of Computer Programming series, was sitting in front of the CHM stage. When reading Knuth’s lectures about typography and typesetting, McCray recognized a shared appreciation for printing, fonts, books, and history. He felt that Knuth’s book on creating digital typesetting, The TeXbook (1986), had to be included in his own book somehow. Fortunately, many of the papers related to the book are at Stanford and many have been digitized.

Carver Mead and Lynn Conway’s Introduction to VLSI Systems, published in 1979, was a textbook, but also a catalyst for the formation of a community. McCray found robust archival materials, for Mead at Caltech and in Conway’s online archive to explore how a textbook about how chips were designed actually had radical agenda.

Patrick McCray explains how a textbook can be radical.

Later, in the ‘80s and ‘90s, Conway told an interviewer that she could see her enduring influence at engineering schools, where chip designs reflected the principles laid out in her and Mead’s textbook.

In addition to books, McCray also included newspapers and newsletters as important media for communicating about the computing revolution. In her Release 1.0 electronics newsletter, business analyst Esther Dyson explained the new world of cyberspace to the average reader in the 1980s and ‘90s and became a regular talk show guest.

McCray included the San Jose Mercury News in his book in order to discuss the evolution of the modern tech journalist. Today, there are hundreds writing about some aspect of the tech industry, but the tech journalist was only beginning to emerge in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s.

People like Evelyn Richards, a Mercury business reporter with traditional journalism training, and freelancer Michael Malone, who had once written promotional copy for HP, began writing about Silicon Valley at a time when mainstream publications were still learning what the place was all about. They helped bring attention and understanding to it, covering both the good and the bad.

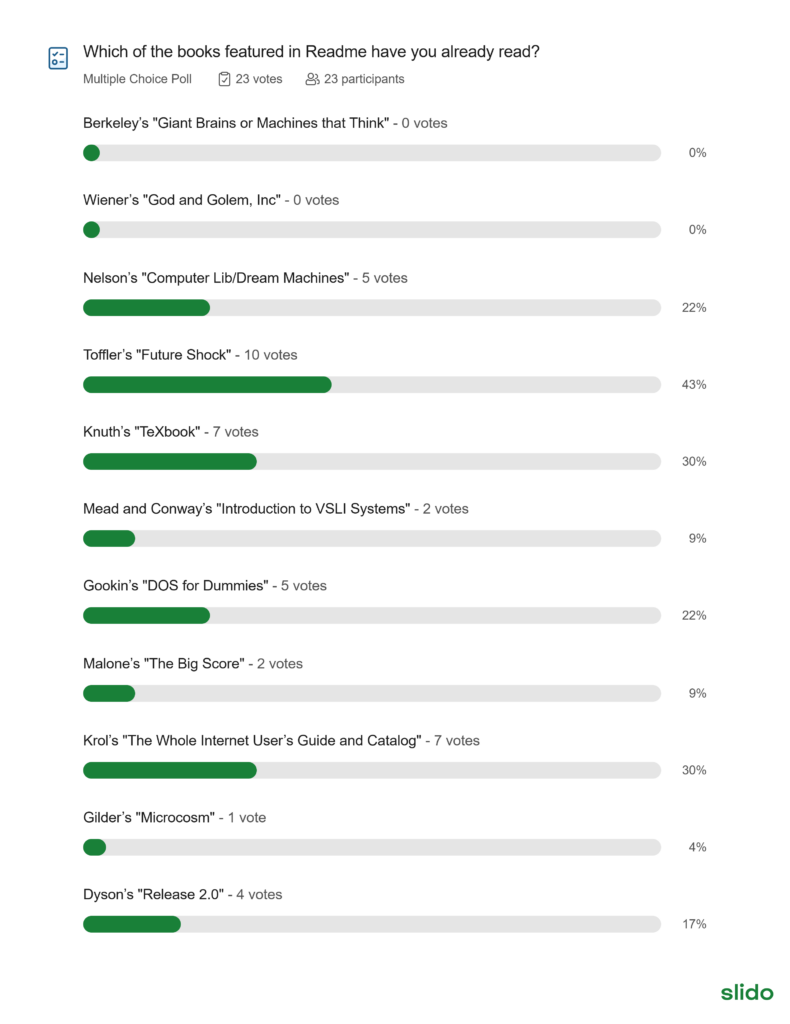

The enthusiastic audience shared their favorite books about computers and computing, with the clear winner being Soul of a New Machine by Tracy Kidder, published in 1981. They also reported what books featured in McCray’s ReadMe they had read. See the results below.

McCray says that one of the most interesting aspects of writing his book was seeing the way that ideas like “author,” “writer,” “publisher,” and “bookstore” were dynamic over the time period he covered. How students learn about books, purchase them and consume them today is very different than in past decades. And introducing AI into the mix is making things even more dynamic. What does it mean when computers become authors? That remains to be seen.

In the meantime, be assured that Patrick McCray wrote every word of his book himself.

ReadMe | CHM Live, January 20, 2026

Free events like these would not be possible without the generous support of people like you who care deeply about decoding technology for everyone. Please consider making a donation.