Industrial design in the 1960s and early 1970s was an important part of Silicon Valley’s transformation from fields and orchards to the world’s center for semiconductor engineering and development. But before glossy press releases and CAD mockups, there were pencils, felt-tip markers, foam-core, and the ingenuity of designers who had to make complex processes legible.

Jerry Nichols, with whom I spent two delightful meetings, belongs to that cohort. Jerry’s early work—spanning semiconductor handling, spin-coat systems, infrared bake ovens, aligners, and chemical distribution—shows how industrial design translated fragile laboratory methods into reproducible machines for a young industry that needed reliability and reproducibility to scale up to mass production.

Jerry Nichols at the Computer History Museum, April 2025.

Born March 7, 1941, Nichols was raised in northeast Indiana and graduated with a BA in Industrial Design from the University of Illinois, Champaign in 1963. He served as a US Army MP from 1963–1965 and moved to Silicon Valley after his military service to begin his design career.

Nichols’s story in the Valley intersects early with the legendary Fairchild Semiconductor Corporation. In 1965–66, working alongside head designer Darryl Staley at JL Brandt & Associates, Nichols contributed to and studied renderings for what he recalls as, “the first Fairchild semiconductor test equipment,” producing renderings that matched a finished unit and a model used for customer approval. The exercise was typical of what industrial designers like Jerry do: showing engineers and executives what a workable product could look like and even how it could be used.

These drawings mattered. In a period when many instruments existed only as benches crowded with components, a coherent external form—operator panel, access doors, safety interlocks—signaled that the machine was ready to leave the lab and enter production, placing this work squarely amid the Valley’s turn from one-off rigs to standardized tools.

First Fairchild Semiconductor Corporation IC Tester, Concept Sketch, 1966.

First Fairchild Semiconductor Corporation IC Tester, Final Product, 1966.

The most revealing thread in Nichols’s early portfolio is the march from hand methods to automated wafer processing.

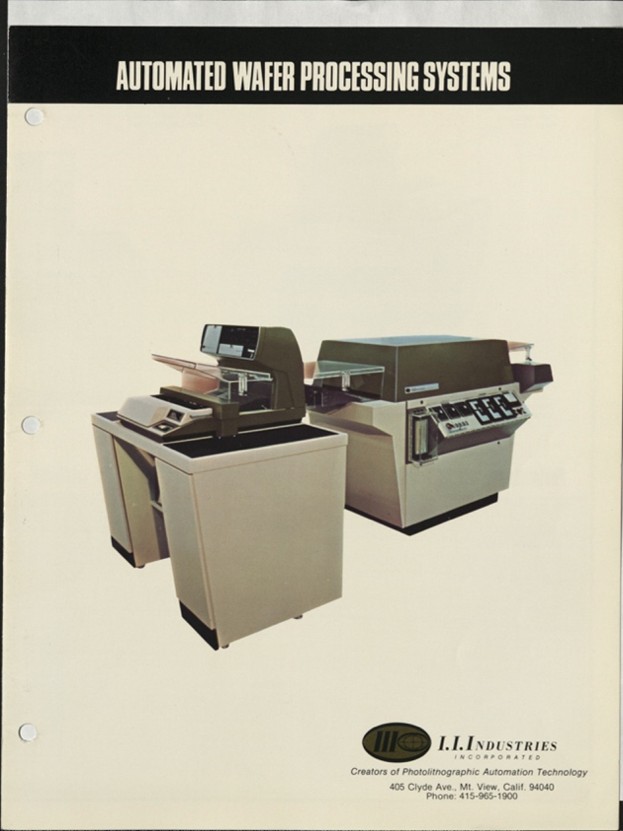

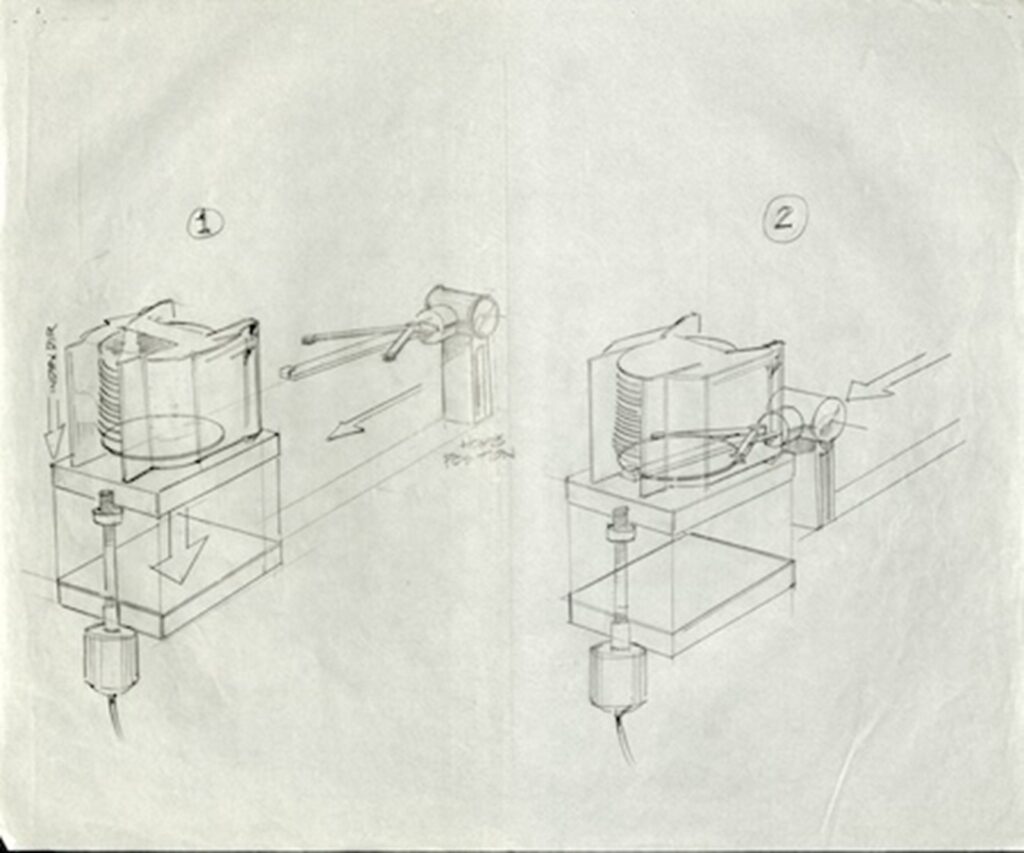

In the beginning, technicians placed wafers on vacuum chucks and dispensed photoresist with eyedroppers—fragile, inconsistent, and slow. Nichols’s work with International Instruments (II Industries) rendered and then refined machines that automated these steps: “spin-bake” units that gripped wafers, dispensed resist, spun them at high RPM for photo deposition, and then handed them off to the next step: infrared (IR) bake ovens. A prototype shell gave way to production cabinets with raised decks, service bays, and clear operator interfaces, forms carefully designed around messy, real-world fluids and maintenance needs.

Crucially, design here was systems thinking. In Nichols’s descriptions, trays moved under a dispense head; the wafer dropped to a vacuum chuck; split catch-trays closed; spin and spray occurred; trays rose and carried the finished wafer downstream. The boxes and panels are the visible part; the choreography—the designer’s translation of process into motion—is Nichols’ achievement.

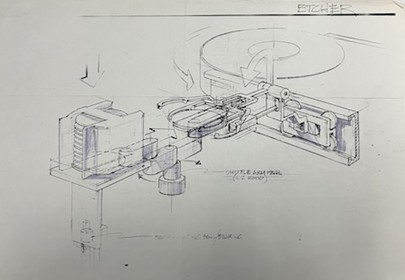

Sketch for internal wafer motion path for silicon wafer etching machine, 1970.

Nichols is quick to point out that his work is a team effort, requiring the talents of mechanical and electrical engineering as well as input from sales and marketing. In particular, he cites his closest collaborators, Don Schuman, lead mechanical engineer, Gene Litton, lead electrical engineer, Gerald Starek, CFO, and Carl Story, the CEO of II Industries.

Prototype Automated Wafer System from I.I. Industries, 1968.

Automated Wafer System brochure from I.I. Industries, 1968.

Nichols’s drawings and photographs also show production IR ovens with three controllable zones, integrated behind the spin modules.

These machines demanded more than a façade; they needed airflow, cooling, access paths, and readable controls in cleanroom conditions already stressed by heat. The design response consisted of elevated decks, removable panels, zoned controllers, and load/unload indexing. The documentation even catches the shop-floor realities: belts, motors, and the sheer bulk of equipment that nevertheless had to live in clean, human-scaled spaces.

Industrial design’s task was to highlight how the heavy and complex could appear precise. In fact, at this time the electronics technology used in II Industries’ products was vacuum tubes and mechanical solenoids. Nichol’s concepts outlined the choreography of internal mechanical movements required for building the first generation of integrated circuit-oriented wafer processing systems.

I.I. Industries Wafer Etching System (Poly Pro cabinet) 1974.

Concept sketch of internal wafer etching handling proposal, 1973.

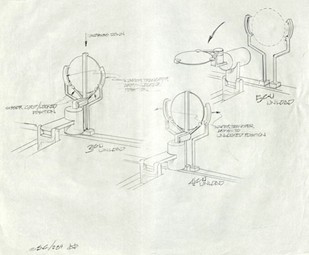

As wafer sizes crept up, tray handling hit limits. Nichols’s later drawings capture the transition to cartridge-based systems, enclosed carriers that sealed wafers from contamination and moved them, robotically, from tool to tool.

Here, the designer’s canvas widens: modules must dock, elevate, and align; control panels multiply; cabinets stretch to twelve feet and beyond. Yet the visual language retains calm, repeatable panel design grammars and sightlines that let operators grasp the system at a glance. The move from two-inch to larger wafers is legible in proportion alone and the design scales without losing clarity.

Sketch showing wafer handling after transition to cartridge-based production, 1973.

Brochure for I.I. Industries IC Wafer Processing System (next generation), 1973.

Not every elegant-looking machine becomes a product.

Nichols preserved images and accounts of an ambitious CRT-assisted aligner: a cabinet with cast panels and integrated optics meant to replace microscope-based, human alignment of photomasks. The technology of the moment couldn’t deliver reliable, fast alignment so the prototype stayed a prototype.

Even here, the record is instructive. Industrial design—indeed CHM’s collecting philosophy—is not just about preserving the winners. Alternate designs are useful for embodying different hypotheses that engineering can then test. That body of “near-miss” hardware is just as much a part of the Valley’s R&D archive as are the successful products.

Semiconductor Mask Aligner, Production Model, 1970.

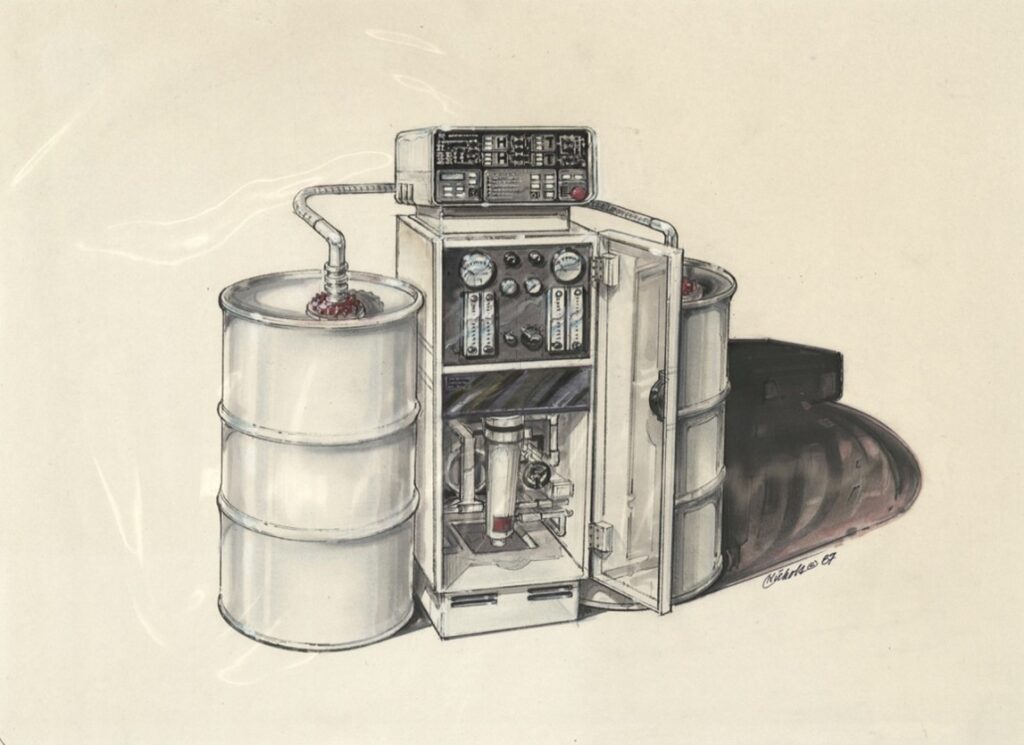

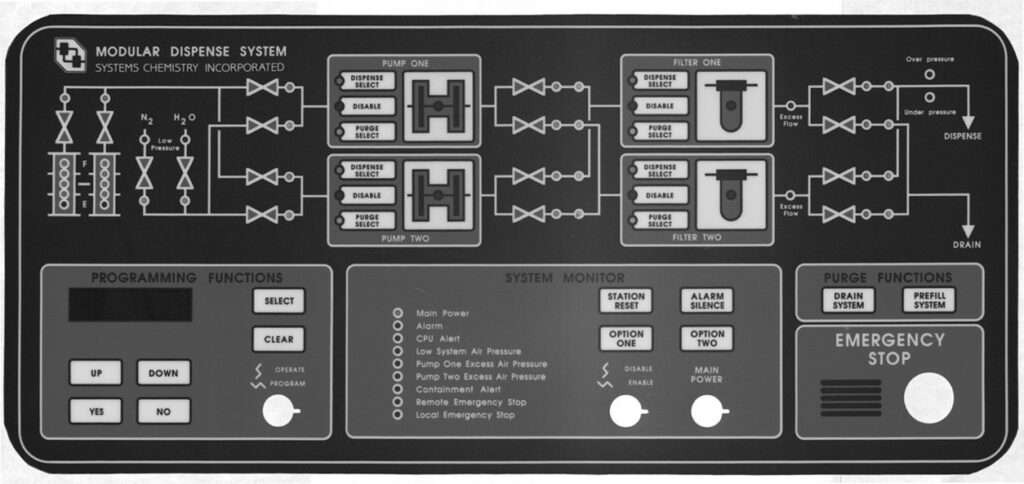

Chemical Distribution System, Systems Chemistry Inc., Concept Sketch, 1979.

Chemical Dispense System, Front Panel Artwork, 1979.

Chemical Distribution System, Systems Chemistry Inc., Final Product, 1979.

Sometimes the best design is a hand tool. Nichols’s vacuum pickup chuck—devised to replace tweezers that chipped wafer edges—shows the same care for interfaces on the smallest scale: a scoop geometry, a flush vacuum channel, and an ergonomic grip. It sold for tens of dollars, not tens of thousands, but it attacked a yield-killing failure mode with elegant simplicity.

Such tools rarely earn museum pedestals; they live in drawers and muscle memory. They also make the machines viable.

I.I. Industries, CD-I Silicon Wafer Vacuum Pickup Tool, 1969.

One of Nichols’s most evocative artifacts is a full-scale foam-core mock-up of an etcher—approximately five feet wide, with meters and knobs set into shaped panels. The craft is notable: kerf-cutbacks to form radii, wood under-frames for stiffness, hot-glue pragmatism. But the real point is the communicative power of Nichols’ drawings. Before a dollar was spent on castings, the team could stand around a believable machine, negotiate heights, reach envelopes, service doors, and the cadence of the operator’s body. Model as meeting, model as argument—that is industrial design at work.

Read as a whole, Nichols’s early work marks the Valley’s pivot from craft to system. He drew and then helped realize the interfaces that let a volatile new industry move from lab bench to production line. His renderings domesticated the unknown for investors and customers; his panels and cabinets distilled complex physics into repeatable procedures; his tools and models improved yield before the word was fashionable.

This is industrial design as infrastructure: the quiet shaping of machines so people can trust them. In an era now mediated by screens, these artifacts remind us that progress once depended on designers who could smell a hot motor, feel a sticky switch, and still imagine how a process might flow when multiplied by a thousand.

Jerry Nichols’s early designs are not just attractive shells over clever mechanisms; they are the design language that taught Silicon Valley how to speak in terms of mass production.