By Marc Weber, CHM Director and Curator, Internet History Program

There’s no topic as white hot in today’s tech press as “agentic” AI. That’s a newish word for what used to be called intelligent agents or intelligent assistants, and from Salesforce to Microsoft companies are investing billions.

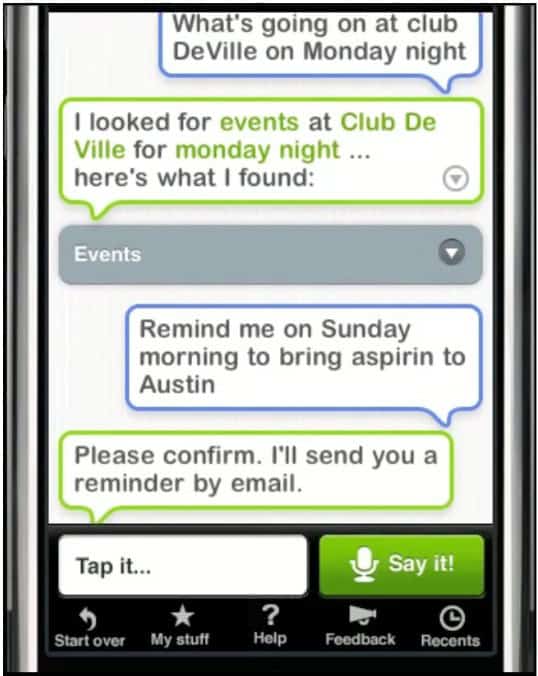

“Agentic” means AI designed to do things for us, rather than simply paint pictures or answer questions like MidJourney or ChatGPT. Think “order me the best Pad Thai you can get delivered here in 40 minutes” or “build us a factory nearby.” When it comes to shooting the breeze, Siri is not nearly as fluent as modern chatbots. But unlike them, she was designed to get things done, and only a portion of her abilities were fully deployed.

What can we learn from a long-secret interview with the team that created Siri, the first wildly successful intelligent assistant, and recent follow-up interviews with both the technical architect and visionary main investors?

In 2013, the cofounders of Siri, Inc. sat down with me and then-CEO John Hollar for an oral history interview on the phenomenon they had started. But there was one condition—that it was not published until they gave the OK. That’s because Siri was still a relatively new and evolving service at Apple.

Released just days before Steve Jobs died in 2011, Siri became a global phenomenon and a household name. Jobs had personally wooed the Siri founders because he saw voice and AI as the future of mobile devices.

Siri CEO Dag Kittlaus on being courted by Steve Jobs.

As the secret interview reveals, Siri was conceived as far, far more than simply an iPhone accessory. Her creators saw her as a new kind of action-oriented interface to the online world with a business model to match. Apple only built out part of that vision of a general-purpose “do” engine. And many of the solutions the Siri team came up with may apply to agentic AI today.

Cofounder Adam Cheyer on challenging venture capitalists with the $20 Siri vs. Google bet.

Since 2022, generative AI like ChatGPT has made AI fluent in free-form conversation for the first time, clearing bottlenecks that have hobbled the field since the 1950s (who wants to work around thousand-pound robots that have trouble understanding orders?). Modern chatbots have also become a new, conversational interface to the internet and the accumulated human knowledge it contains, as well as our co-conspirator in writing bad poetry.

From a demo of the original Siri app, courtesy of Adam Cheyer.

But key challenges to making AI a useful agent remain unchanged: Integrating a number of components, including online services, into a smooth process from start to finish. In essence, generative AI has made some of those components smarter and much, much more fluent. But it is only beginning to address the central systems integration challenge—how to orchestrate them into a useful whole that gets things done.

If your AI agent finds a highly rated restaurant but doesn’t coordinate with a mapping service for reasonable travel times, your Pad Thai may arrive too late. Or, your factory-building agent may not integrate properly with the AI plumbing agent or AI zoning consultant. Our oral history interview with the Siri team talks about their solutions to these kinds of issues, including the Active Ontologies meta-language they developed with Chief Scientist and longtime collaborator Didier Guzzoni used to create AI modules and orchestrate them together within one unified AI development framework.

Cofounder Tom Gruber on systems integration and how agentic AI is like assembling a 747.

Also still in flux is the business model around intelligent agents. Much of today’s online world is paid for by AI-driven contextual advertising, originally developed for search in the late 1990s and now served across content from social media to streaming sites. But where advertisers pay for the chance to entice consumers into spending money, an intelligent assistant can jump straight to the final transaction itself. That was Siri’s pre-Apple business model. Besides buying conventional ads in the hope they might entice you into booking a stay, a hotel could also pay Siri a far higher commission out of actual, completed sales.

Venture investor Gary Morgenthaler on Siri’s original business model

Of course, AI agents don’t all have to be personal assistants like Siri or Alexa. Many of the use cases for “agentic” AI are around agents within organizations, from customer support to HR, or any number of other roles currently filled by humans. But the skills that make an AI agent flexible enough to be an effective intelligent assistant are likely to carry over to those roles as well.

Last year, CHM finally got the green light to release the Siri oral history. But first, curators wanted to close the gap with the investors brave—or prescient—enough to take a chance on Siri before it was even a company. They talked with Siri’s initial investor, Shawn Carolan of Menlo Ventures, who was interviewed for the Chatbots Decoded: Exploring AI exhibit (opened November 2024). I conducted a new interview Siri’s second investor and later board chair Gary Morgenthaler of Morgenthaler Ventures. CHM had interviewed Gary back in 2005 for his earlier roles as a venture capitalist and cofounder of Oracle competitor Ingres, but that was before his roles at Siri. In the meantime, I also re-interviewed Siri cofounder and AI pioneer Adam Cheyer for the Chatbots exhibit, where he talks about LLM chatbots in light of what came before.

Check out additional video and transcripts below:

Explore a timeline of four highlights in the history of agentic AI, from the dream of a “Siri” for the 1960s ARPAnet through Siri herself.

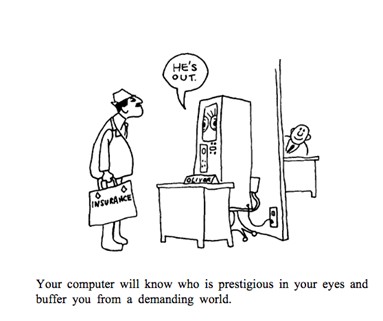

OLIVER, illustrated in “The Computer as a Communication Device,” by J.C.R. Licklider and Robert W. Taylor, Science and Technology, April 1968.

By 1968, fictional AI assistants already included the Star Trek ship’s computer and the less dependable HAL from the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey.

That same year, computing greats J.C.R. Licklider and his protégé Bob Taylor described an intelligent assistant they called OLIVER, in honor of the AI pioneer who had originally come up with the idea. British department store scion Oliver Selfridge had helped kickstart machine learning, as well as the iconic Dartmouth conference that gave AI its name.

Licklider and Taylor hoped OLIVER the AI agent would one day live in the network they were starting to build as the ARPAnet, and help users with daily tasks.

Today we mostly remember Licklider and Taylor as champions of augmenting human intelligence. Both were funders of Doug Engelbart’s work at SRI, and Taylor went on to midwife one birth of the personal computer at Xerox PARC. But both had also heavily funded AI as heads of computing at ARPA, and Licklider had proposed mild AI to help sort the world’s knowledge in Libraries of the Future. He was even confident that human-level AI was possible. He just thought it could take between 20 and 500 years, and he was in no hurry. As he wrote of the interim period of human-computer symbiosis: “…those years should be intellectually the most creative and exciting in the history of mankind.”

Fifty-six years after Bob Taylor kicked off the ARPAnet, later absorbed into the internet, we’re still mostly waiting for our OLIVERs.

From left to right, Oliver Selfridge, Nathaniel Rochester, Ray Solomonoff, Marvin Minsky, Peter Milner, John McCarthy, Claude Shannon at the 1956 Dartmouth AI conference that Selfridge helped to organize. Credit: Photo by Nathanial Rochester/Courtesy The Minsky Family

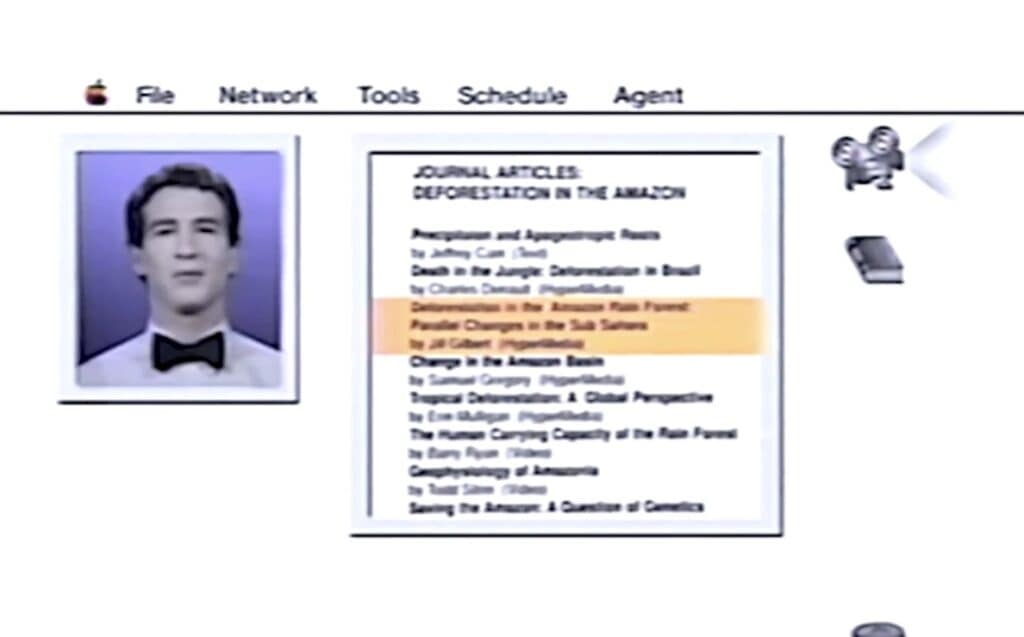

After helping drive Steve Jobs out of Apple, CEO John Sculley needed to show his own vision for computing. That was a reach for a former Pepsi executive. So he drew on Apple’s Advanced Technology Group to develop the 1987 “Knowledge Navigator” concept video. In it, a professor of climate science uses a mobile, wireless tablet to arrange his day. Instead of a stylus, his fingers brush iPhone-like along the color touch screen. An AI assistant appears as a bow-tied young man who tracks down a colleague by video while fending off calls from the professor’s mother. The assistant chats fluently, even finishing the professor’s sentences, while searching something like CompuServe or the future web. (The year is supposedly 2011, the year that Siri will, in fact, launch on the iPhone.)

Still image from Knowledge Navigator video.

Within Apple, the AI assistant part of the Knowledge Navigator vision soon faded back into a “someday” future. So did the wireless connectivity, with real mobile data networks still taking baby steps. But the mobile, keyboardless computer was cool, too. And it was actionable. So began the Apple Newton, a pen-based mini tablet. Newton would ultimately fizzle, but inspire both handheld computers and smartphones to come.

Within Apple, a few remained as interested in the wireless, intelligent assistant parts of the Knowledge Navigator vision as the pen. In 1990, a dream team of past and future stars split off expressly to develop a handheld around being wirelessly connected all the time. They modestly named their stealth startup General Magic, and the operating system Magic Cap. The goal was not just to connect people through wireless links. They also wanted to connect AI-inspired virtual “agents,” little bits of servant software that might, say, order lunch or find you the best airline reservation. Their leader was charismatic Marc Porat, whom the Wall Street Journal called a “silver tongued devil.”

As Porat hammered home to partners at Sony, AT&T, Toshiba, Motorola, and beyond, General Magic had a complete alternative vision for the future. We would soon be connected 24/7 to a “cloud” of software, sites, and services through the handy communicators in our pockets and purses. Gone would be the need for a lot of conventional desktop and portable computing. Also gone would be the need for the communicator to be a powerful computer in its own right, like most other handhelds. It could be more like a terminal.

This magical vision eerily foreshadowed our smartphone world of today. But the hardware of the early 1990s did not. Nearly all the pen machines, not just those running Magic Cap, were big, heavy, slow, expensive, and arrived years late.

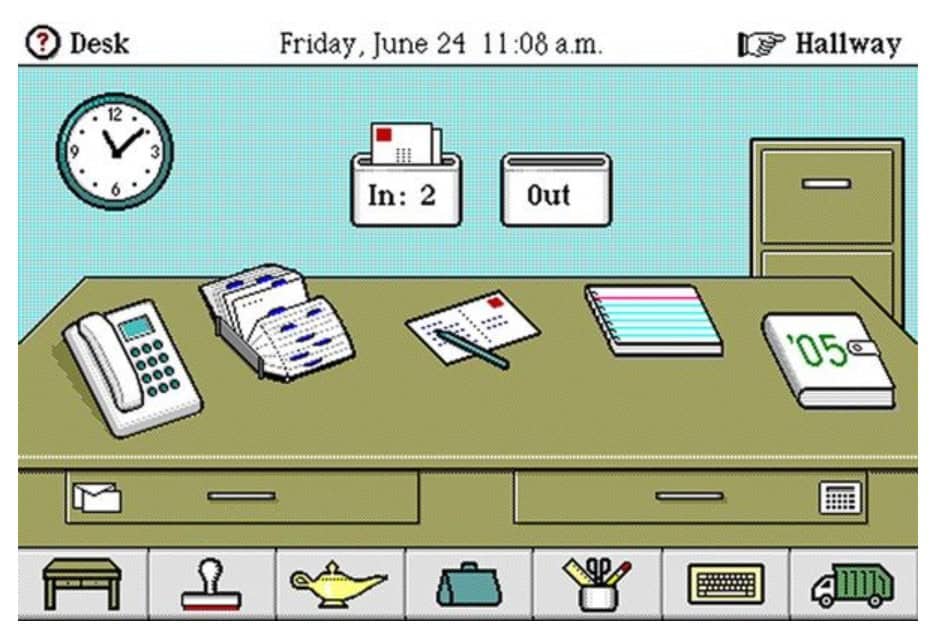

Magic Cap operating system screenshot, 1984. Courtesy of Marcin Wichary. © General Magic.

Steve Jobs died of a rare form of pancreatic cancer just days after Apple announced Siri as an intelligent assistant for the iPhone on October 5, 2011. He was 56. Jobs had personally wooed Siri’s creators Adam Cheyer, Tom Gruber, and Dag Kittlaus, and bought the tiny AI startup in 2010 for an estimated $200 million. He saw it as the mobile future. Gruber remembers him saying: “I’m going to transform this phone… you won’t have to tap and type all the time anymore. I want to be able to use this thing on the go in a natural way.” It was an end run around the limited interface of tiny handhelds. Who needed keyboards or handwriting recognition when you could just talk?

The Siri, Inc. team. Courtesy of Adam Cheyer.

Siri, which means “beautiful woman who leads you to victory” in Kittlaus’s native Norwegian, was a try at the conversational features in Apple’s 1987 Knowledge Navigator concept video. But it came out of decades of research into integrating different AI components into a useful assistant—work cofounder Adam Cheyer, Chief Scientist Didier Guzzoni, David Martin, Luc Julia, and others had done at SRI International and beyond under federal and commercial grants. (In pre-release demos, Siri was ironically named HAL, after the infamous AI in Stanley Kubrick’s film 2001: A Space Odyssey, mentioned above.)

Venture investor Shawn Carolan on the revenue split under the original Siri business model.

Intelligent assistants are the friendly side of AI dreams. Like Licklider and Taylor’s 1960s imagined OLIVER for the ARPAnet, they were meant to augment—not replace—human abilities. In fact, Adam Cheyer and Tom Gruber were huge fans of Doug Engelbart’s pioneering work on augmentation.

Siri CEO Dag Kittlaus on needing another founder.

Siri proved a shadow of the general fluency imagined for the Knowledge Navigator. The version Jobs released was an Apple-centric version of the Siri team’s own first product. But unlike the more rigid voice commands supported on Android (and on Mac since the early 1990s), Siri felt conversational. She could understand some open-ended requests like “please find me a good place to eat nearby.” Or even respond with corporate humor: User—“I love you Siri.” Siri—“All you need is love—and your iPhone.” Siri could make an appointment or dial a number hands-free, as long as you didn’t mind being overheard—a perpetual blemish on voice interface dreams.

Soon, Amazon’s Alexa would bring Siri-like abilities to the home on the Echo smart speaker, and Google stepped up its existing voice search efforts. Chatting with computers was becoming ordinary, the last interface revolution Steve Jobs had helped launch.

Adam Cheyer, Dag Kittlaus, and Chris Brigham went on to found Viv Labs in 2012 to build on the original Siri vision. They sold Viv Labs to Samsung in 2016, and parts of Viv live on in Samsung’s assistant Bixby. But Samsung did not promote an intelligent assistant as aggressively as Apple had, and neither phone maker embraced the original vision of an assistant as center of a web of interconnected services.

Generative AI has brought us chatbots of unparalleled fluency, depth, and creativity. But the general purpose “do” engine—the heart of agentic AI—remains an unfinished revolution.

Cofounder Adam Cheyer on what’s still missing today.