CHM curator David C. Brock shares the story of a remarkable discovery…

It seems to me that every item that enters the Museum’s collection has a biography of sorts—a life before CHM, a tale about how it came to us, and a life within the Museum. A chapter of the item’s biography are the uses made of it, the historical and interpretive stories it can be made to tell. This is a biography of one item that has entered the Museum’s collection—an early Memorex video tape containing a recording from 1968—and an historical discovery it has afforded.

Our biography begins in May 2020, with an email. Dr. Debra Dunlop, a dean at New England College, wrote to the Museum about a large collection of documents, audiovisual materials, and a rare computer, a Xerox Star, in New Hampshire. These were the professional papers of Debra’s father, Dr. Robert Dunlop, and she knew how dearly he valued the collection. She was helping her father move to an assistive facility, and she had to make some sort of plan for this extensive collection. What did the Museum think?

Robert Dunlop in early 1966, detail from a photograph in the Dunlop collection at CHM.

For me, thinking about the Dunlop collection was a light in the darkness. It was spring of 2020. The death toll in the US from Covid-19 was nearing 100,000, with a vaccine shot for me months in the future. I was nervous working from home in Massachusetts because the Museum—like all places that depend in part on ticket sales—faced strong financial pressures, and I didn’t know how long it could go on with its doors closed. The Dunlop collection sounded interesting. Robert Dunlop had been an industrial psychologist working to develop “bleeding edge” systems at IBM, RCA, and then Xerox. The collection wasn’t far away, and perhaps there was a way I could safely go and have a look.

I learned more about Robert Dunlop’s career from Debra, and she and her family moved the collection to a garage where, after we let it sit for a week, we felt it would be safe for me to go up and review the collection alone, wearing a mask, with the garage doors open.

After the visit, I discussed what I had seen with my colleagues, and we agreed that I would return and select, pack, and ship out a substantial portion of it. Debra and her family very kindly made a financial donation to the Museum to help with the shipping expenses in that difficult time for CHM.

Packing up 30 boxes of the Dunlop Collection on August 13, 2020. Photo by David C. Brock.

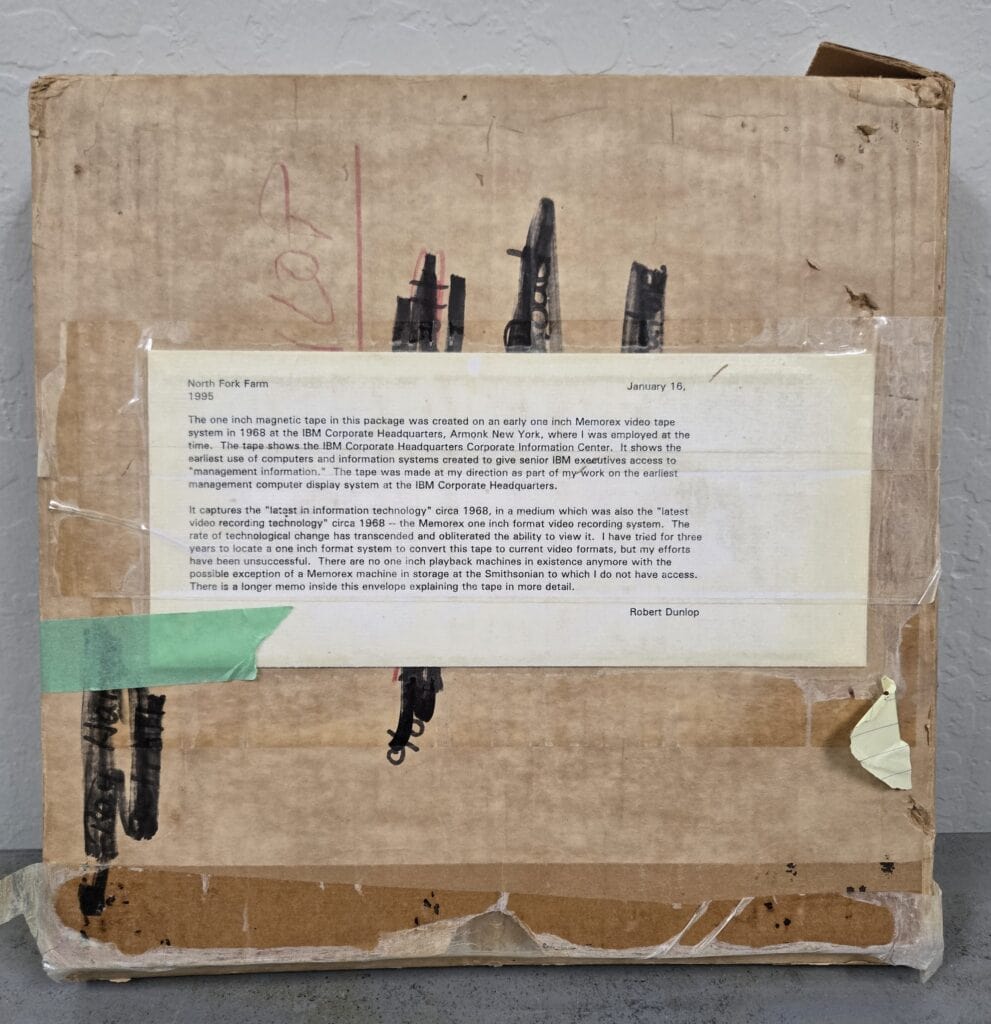

In my work with the collection in that New Hampshire garage, one item absolutely fascinated me. This was an early video recording, made in 1968, that clearly had great meaning for Robert Dunlop. It was a 1” format tape on an open reel, carefully packaged, and with an explanatory note by Dunlop taped to the outside and a longer letter from him tucked inside. Both notes told of an inventive computer system at IBM headquarters that I’d never heard anything about. A demo of the system was captured on the long obsolete video.

The outer packaging of the 1968 video tape, with Robert Dunlop’s note attached. Photo by Penny Ahlstrand.

In 1995, when Dunlop wrote the notes, he had despaired of finding any working equipment to recover the recording. For a moment, while the tape rested in my hands, I wondered, “Should I even collect this if it’s impossible to watch?” But then I thought, “Perhaps we can figure something out. And if not us, maybe something could happen in the future.” I decided to take my chances and collect it.

The Dunlop collection started its new life in the Museum, carefully rehoused into archival storage boxes and added to our backlog for archival processing. A grant to the Museum from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation presented an opportunity to digitize some of the audiovisual materials in our collection in 2023. When consulted about priorities, one of the items I picked out for consideration was Dunlop’s 1968 video recording. Could we give it a try?

The Dunlop collection rehoused at the Museum’s Shustek Research Archives. Photo by David C. Brock.

Dr. Massimo Petrozzi, CHM’s Director of Archives and Digital Initiatives, reached out to his networks to see if there was someone who could help. A contact in Europe pointed back to the States, to George Blood and his firm George Blood LP outside of Philadelphia. Blood’s firm is a major provider of audio and moving picture preservation services, boasting an enormous collection of equipment including, as it happens, an Ampex video unit capable of recovering video Dunlop’s tape, what Blood calls a “very early technology.” Blood and his colleagues after painstaking adjustments and experiments were able to recover and digitize Dunlop’s silent video, fulfilling Robert Dunlop’s long hopes. Sadly, Robert Dunlop did not live to see his recording again. He died in 2020.

What about the recording itself? Along with photographs and documents in the Dunlop collection, it reveals a story as interesting as it is seemingly forgotten.

The Dunlop video tape. Photo by Penny Ahlstrand.

You may already be aware of the “Mother of All Demos” presented by Doug Engelbart and the members of his Stanford Research Institute center at the close of 1968. This presentation, with Engelbart on stage at a major computing conference in San Francisco, displayed the features and capabilities of his group’s “oN-Line System,” known as NLS. The system included many elements that were extraordinarily novel, even for the assembled computing professionals: networked computers, video conferencing, graphical interfaces, hypertext, collaborative word processing, and even a new input device, the computer mouse.

This remarkable 1968 demonstration of the NLS was, surprisingly and much to our benefit, recorded on video tape. Although relatively early in video technology, the quality of the surviving recording is remarkable and readily available online today.

Behind all the individual novelties, the NLS was driven by a particular vision for the future use and practice of computing: a vision that centered on the notion of alliance. This vision was one of individuals joining together into teams and organizations, directly using new computing tools and approaches for creating and using knowledge, and in doing so, “augmenting human intellect” to better solve complex problems.

Wholly unknown to the history of computing—until now—is another video recording of another fascinating demonstration of another advanced computing system that also took place in 1968: the recording from Robert Dunlop’s video tape.

This second demonstration took place on the East Coast, at IBM’s headquarters in Armonk, New York, and was motivated by a far different, perhaps one could go so far as to say an opposite vision for the future of computing. This vision centered not on alliance, but rather on the concept of rank. The system was known as the IBM Corporate Headquarters Information Center, and was the culmination of Dunlop’s experiment with executive-computer interaction at the company.

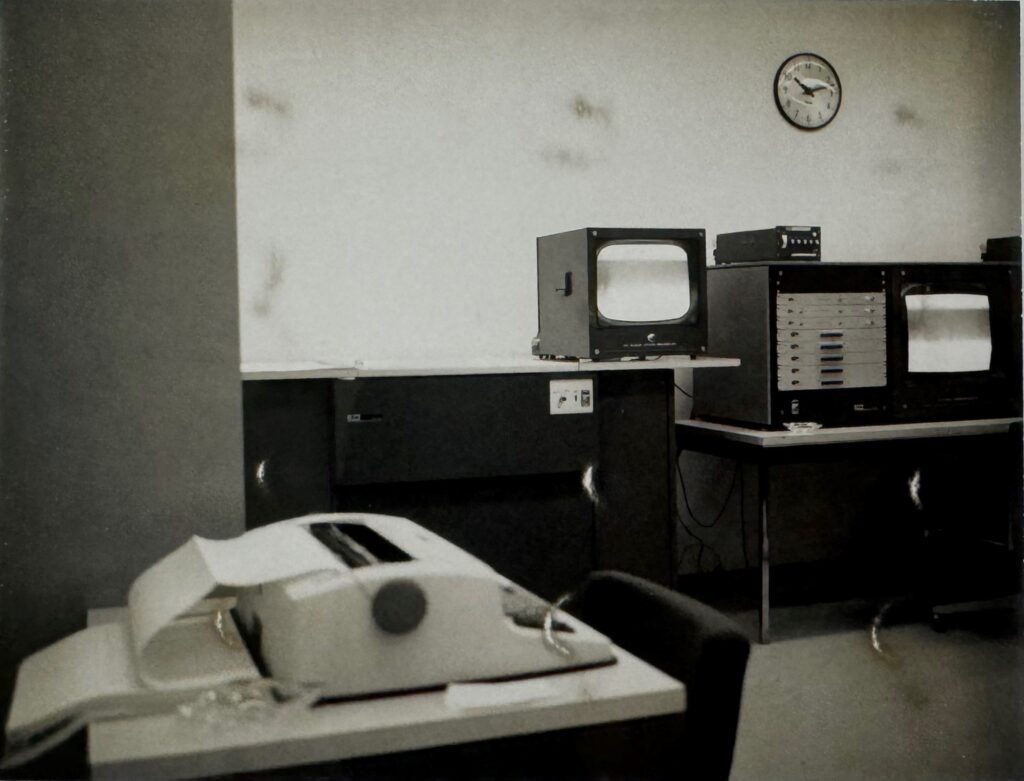

With the new IBM Headquarters Information Center, Dunlop saw the opportunity to run another experiment in 1967-8, which he called the “Executive Terminal.” The lead information specialist in the Information Center would sit at a video mixing and control console, equipped with a video camera, microphone, and even lighting. The executive user, in their office, turned to the Executive Terminal, a modified television set with an audio and video connection to the console in the Information Center.

The executive could press a button, summoning the information specialist and their live video image to the screen. Remaining unseen, the executive could place an inquiry. The information specialist then directed other staff in the Center to gather the appropriate information to answer the request: models were run on CRT terminals, documents and data were gathered on typewriter terminals, microform could be loaded into a video reader, paper documents could be placed on a video capture unit.

A partial view of the Information Center. At far right, central video control station. At left, the hard copy station for creating a video image of printed materials. A typewriter terminal is in the foreground. From the Dunlop Collection.

Once assembled, the information specialist conveyed all this information to the executive, cutting from one video feed to another, guided by the executive’s interest and direction. It is unclear what ultimately became of the Executive Terminal and the Information Center, as they appear to have left little to no historical traces beyond a few documents—like the unpublished talk—a few photographs, and Dunlop’s remarkable 1968 video recording of the system’s demonstration.

Dunlop’s 1968 video demonstration of the Executive Terminal and the Information Center proceeds in three acts.

The first ten minutes of the video shows the information specialist and other staff in the center responding to an executive’s request, finding and preparing all the materials for video presentation, using typewriter and CRT terminals, and even engaging in video conferencing with another employee.

The second five minutes show the executive’s use of the Executive Terminal to receive all of the information by the video link, and the ways he is able to direct the display and flow.

The final few minutes show the information specialist working on an IBM 2260 video computer terminal, still then a relative novelty that was used for database and model access.

With Engelbart’s and Dunlop’s 1968 demo videos, we now have a remarkable and contrasting snapshot in time of two very different directions in advanced computing. Engelbart’s Mother of All Demos showed how advanced computing could create a shared, collaborative environment of allied individuals, all direct users of the same system, befitting of a laboratory of computer enthusiasts in Menlo Park, California. Dunlop’s Executive Terminal demo showed how many of these same advanced technologies could be directed along another path, that of a strictly hierarchical organization, highly attuned to rank and defined roles and specialties. While these were very different, perhaps opposing directions, they shared a common commitment to the use of advanced computing for organizing and analyzing information, and taking action.

Engelbart held that his system was for the “augmentation of the human intellect,” so that we might better address complex problems. For Dunlop, the Executive Terminal was an answer to his question, “Can we make better decisions, at higher levels, through better information processes?” While there are echoes of Engelbart’s Mother of All Demos around us every day—the hyperlinks of the Web, the scuttling of mice on desks, editing online documents together, and more—the echoes of Dunlop’s Executive Terminal demo redound on us loudly as well. In it, one can see the video conferencing and screen sharing practices so familiar in the Zooms, Teams, and Meets of coworkers within organizations today.

The Computer History Museum is pleased to make public Dunlop’s entire 1968 demonstration video recording.

The work of any one person at any museum (or anywhere) is actually the work of many, and that is certainly true here. I’d like to thank the trustees and financial supporters of the Computer History Museum for making these efforts possible, especially the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and Gardner Hendrie. At the Museum, I’d like to thank my collections colleagues Massimo Petrozzi, Penny Ahlstrand, Max Plutte, Kirsten Tashev, Gretta Stimson, and Liz Stanley. I’d also like to thank historian Jim Cortada for giving this essay a reading, to David Blood for recovering the recording, to Heidi Hackford for editing and producing this essay, to Debra Dunlop for thinking of the Museum, and to the late Robert Dunlop for taking such care of these materials in the first chapters of their life.