Recently, Intel ETANN pioneer Mark Holler donated a pair of Intel 80170 ETANN integrated circuits and other materials related to early neural networks to the Computer History Museum.

Neural networks are very much in the news these days as the enabling technology for much of the artificial intelligence boom, including large language models, search, generative AI, and chatbots, like ChatGPT. Yet this idea has deep roots in past work going back to the 1950s with the work of Professor Frank Rosenblatt at Cornell University, who built devices that could recognize simple numbers and letters using the world’s first neural network, the Perceptron, which he invented.

Frank Rosenblatt, left, and Charles W. Wightman work on part of the unit that became the first perceptron in December 1958. Credit: Cornell University, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections.

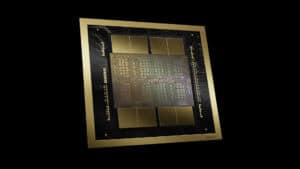

Over the course of several AI “Winters” since that time—during which the generous government funding dried up—neural networks have been in the background waiting for their moment. That moment came about a decade ago as the power of computing driven by Moore’s Law allowed for a new level of neural network complexity, resulting in “neural nets” being deployed in real-world contexts. For example, Google’s 2013 Tensor Processing Units are essentially neural network accelerators that Google uses to improve search. NVIDIA, Amazon, Meta, and (again) Intel have all designed their own neural network processors.

NVIDIA Blackwell AI Accelerator

Meta Training and Inference Accelerator (MTIA)

Intel Gaudi 3 AI Accelerator

While there have been many such milestones in neural networks, especially recently, a very interesting and unique implementation of neural networks took place in 1989 with the announcement of Intel’s 80170 ETANN integrated circuit at that year’s International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN).

ETANN stands for Electrically Trainable Analog Neural Network. Neural networks aren’t really programmed in the traditional sense, they are trained. An AI programmer’s job is therefore not writing instructions per se but organizing the data you give a neural network in such a way that it can—through repetition across multiple “layers” of these networks—discover patterns and information from incomplete information. Some might call this a form of “thinking.” Others, notably commentator Emily Bender et al, in a now-famous paper, consider neural networks and the large language models they support a form of “stochastic parrot,” not involving thought at all but just a clever statistical parlor game.

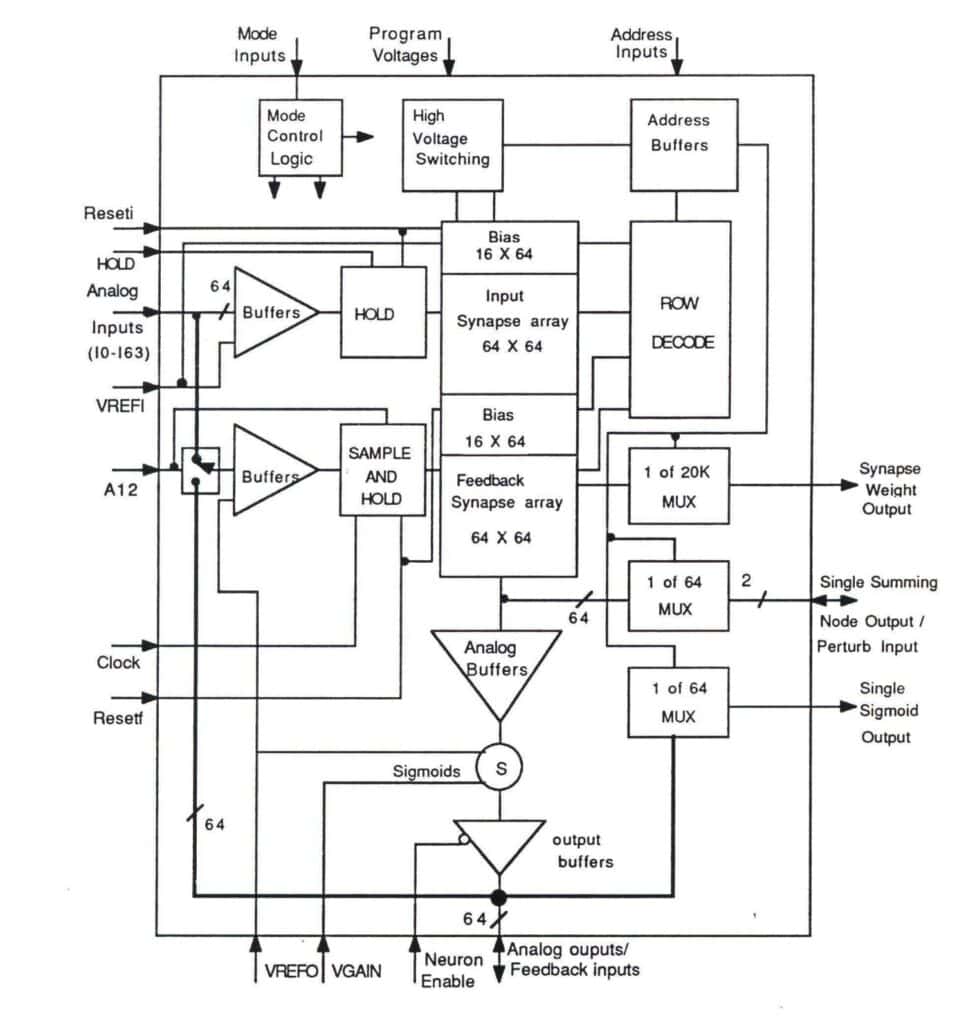

Back to the ETANN: In practical terms, to “feed in” the data to the neural network, Intel provided the Intel Neural Network Training System (iNNTS), a training device accessible by a standard Intel PC. Intel also provided a set of software and drivers for controlling the iNNTS. The ETANN incorporated 64 analog neurons and 10,240 analog synapses. At the time, neural networks were pretty much a dead end in terms of applications. There was neither the computing power nor the understanding to deploy them at scale in useful applications, though there was at least one attempt in the military to base a missile seeker on the 80170 chip. As personal computing columnist John C. Dvorak wrote at the time, “Nobody at Intel knows what to make of this thing.”

Block diagram of Intel’s ETANN 80170 chip.

But the potential seemed there, if only a bit into the future. As Pashley recalled in a recent email, “… I remember when Bruce McCormick first became interested in Neural Nets. It was sometime in the winter of 1987-88 when Bruce and I were on an Intel recruiting trip to Caltech. On this trip to Caltech, we met with Carver [Mead] to talk about his EE281 Integrated Circuit Design students and ended up talking about the potential of Neural Nets. Personally, I knew nothing about Neural Nets, but Carver and Bruce were really excited. On the flight back to Intel, Bruce was bubbling with ideas to use EEPROM and Flash Memory to test out Neural Net’s potential.”

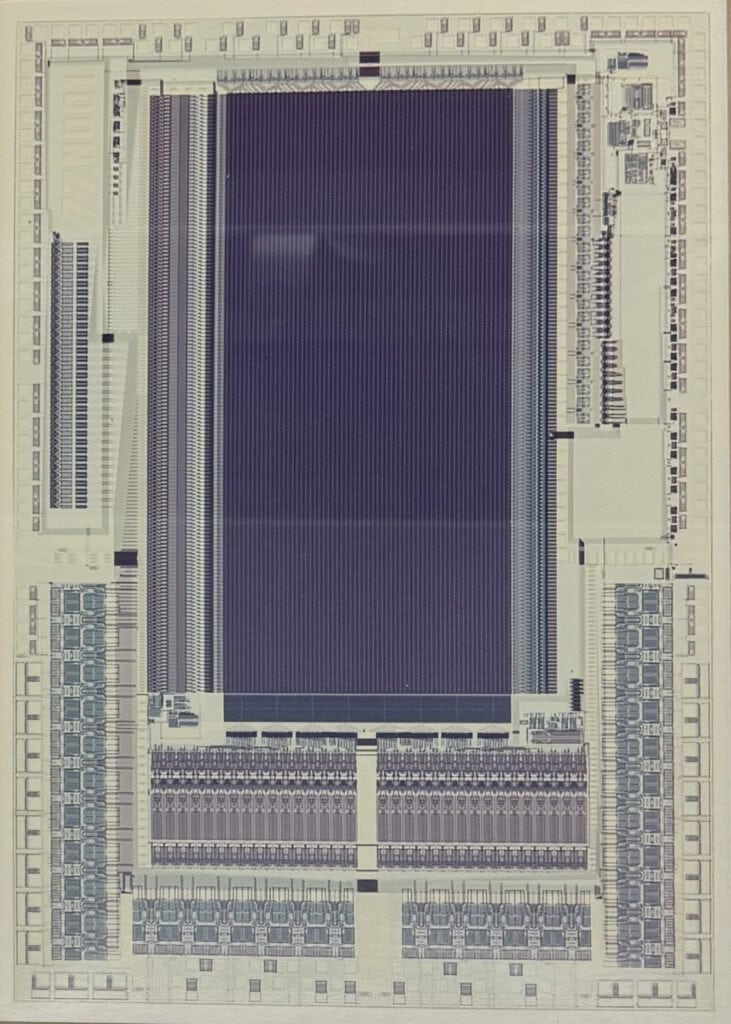

Intel 801700 ETANN Neural Network Integrated Circuit, 1989.

Like other ideas “ahead of their time” in the history of technology, we see in the Intel 80170 chip the earliest implementation of a reasonably sophisticated neural network in silicon, a prefiguring of the more complex—indeed, world-changing—AI accelerators of today.

Holler, Mark, et al. An electrically trainable artificial neural network (ETANN) with 10240 floating gate synapses. International Joint Conference on Neural Networks. Vol. 2. 1989.

Castro, Hernan A., Simon M. Tam, and Mark A. Holler. Implementation and performance of an analog nonvolatile neural network. Analog Integrated Circuits and Signal Processing 4.2 (1993): 97-113.

L. R. Kern, Design and development of a real-time neural processor using the Intel 80170NX ETANN, [Proceedings 1992] IJCNN International Joint Conference on Neural Networks, Baltimore, MD, USA, 1992, pp. 684-689 vol.2, doi: 10.1109/IJCNN.1992.226908.

CHM Donation Interview with Mark Holler: https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/4ybj210gjtmlxwp7pfg71/Mark-Holler-Interview.mp4?rlkey=68wvbse2js7ntmb5w6zb3fn2u&e=1&dl=0

On Frank Rosenblatt: Professor’s perceptron paved the way for AI – 60 years too soon, https://news.cornell.edu/stories/2019/09/professors-perceptron-paved-way-ai-60-years-too-soon

On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? FAccT '21: Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, March 2021, pp. 610 – 662.

The ETANN chip was a team effort by some very talented engineers. Here they are:

In the image at the top of the article and above: back row on far left, Hernan Castro; back row second from left, Been-Jon Woo; back row third from left, ?; back row fourth from left, Ken Buckmann; back row holding chip, Mark Holler; back row far right, Mike Roy; front row on left, Lily Law; front row middle, Simon Tam; front row far right, ?

This donation would not have been possible without first hearing about the 80170 from CHM Semiconductor Special Interest Group (SEMISIG) member Jesse Jenkins. The historical and research assistance of SEMSIG chair Doug Fairbairn and Intel Alumni Network member Dane Elliot were invaluable in effecting the donation of the historical hardware and supporting materials from donor Mark Holler, to whom, of course, we offer our deepest thanks for this donation.