Aspen Movie Map, Aspen Colorado, c. 1980. Credit: MIT Architecture Machine Group

Google Street View, Aspen, Colorado, c. 2012. Credit: Google Inc.

Market Street, San Francisco, 1905. Credit: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco

Google Street View, Market Street, San Francisco, 2012. Credit: Google Inc.

Choose a spot on a map and you are there—immersed in a panoramic view you can move and zoom. Since 2007, Google Maps with Street View has transformed our ideas about going places, from faraway lands to a restaurant across town.

Computerized, interactive “movie maps” go back 35 years. Today’s connected computer power is turning tools that were once the province of artists and visionaries into a part of everyday life.

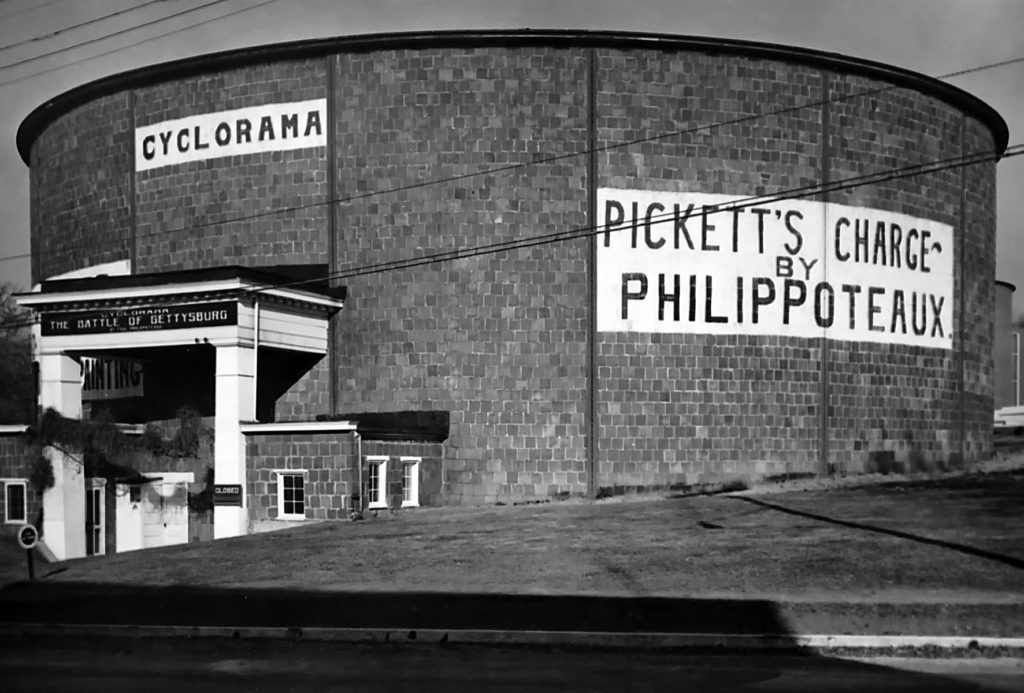

The outside of the popular Gettysburg Cyclorama, which opened in 1913. Credit: Gettysburg National Military Park

In April, 1906, a filmmaker named Earl Miles attached a movie camera to the front of a trolley in San Francisco and filmed all the way from mid-Market Street down to the Ferry Building. Pedestrians in hats wander across the tracks mixing chaotically with horse-drawn wagons and flimsy-looking early automobiles. He advertised the footage for sale in a film magazine.

Less than a week later, the great earthquake and fire destroyed most of what the camera saw, and killed or made homeless many of the people who had stared curiously into its lens. The photographer’s own offices on Market Street were destroyed, and if the film hadn’t been shipped off to New York the night before the quake it would have been, too. Today, this footage offers an excruciatingly poignant glimpse of what it was like to wander through a lost world.

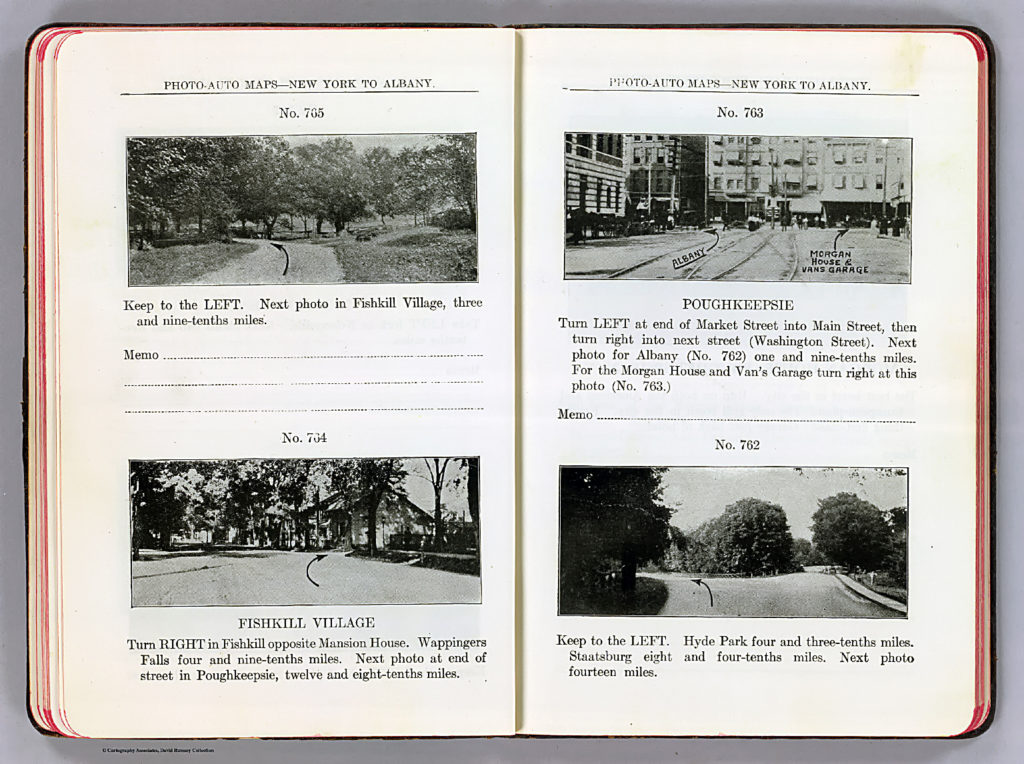

Rand McNally Photo-Auto Map, New York to Albany route, 1907. Credit: David Rumsey Historical Map Collection, © 2012 by Cartography Associates

From cave paintings to 1950s 3-D movies, artists and photographers have long used the best techniques at their disposal to immerse viewers in a distant scene. One 16th century Chinese panorama of a famous battle stretched 85 feet. Cycloramas—round rooms with realistic views painted on the inside—were popular tourist attractions in the 19th century.

An early use of the movie camera was for virtual walks down city streets, like the fateful 1906 tour of Market Street. In the 1970s, California filmed all the state’s main highways from a car-mounted camera.

The practical side of street views has a history, too. Before roads had consistent names and signs, landmark-by-landmark photo guides called Photo-Auto maps were one effective way to specify a route for the early motorist.

Aspen Movie Map camera vehicle, ca. 1978. Credit: MIT Architecture Machine Group

With traditional panoramas and movies, the viewer can only see a predetermined scene or route. By adding computer control, MIT’s 1978 Aspen Interactive Movie Map changed all that. In this stunning touchscreen-controlled drive-through of Aspen, Colorado, the viewer was in charge of the tour and could go wherever he or she wished. The project pioneered basically all of the features of street view and other mapping services today, including navigation buttons for turning and moving, integration with flat maps and aerial photography, computer-generated panoramas, and 3-D models of buildings.

Using the Aspen Movie map from an experimental rig, ca. 1980. Credit: MIT Architecture Machine Group

The Aspen Movie Map was funded as a way to familiarize soldiers with remote locations—”surrogate travel”. It was inspired by the success of the Israeli raid on Entebbe in 1976, where commandos successfully freed hostages after practicing on a mockup of the real location. The technology was cutting-edge for the time. Nicholas Negroponte of the Architecture Machine Group at MIT (later the Media Lab) realized that the newly developed laserdisc player—which used shiny disks like giant DVDs

—could do far more than play videos start to finish. By controlling it with a computer you could create customizable multimedia, with endless links and branches chosen by the user. Selecting a building in the Movie Map worked like a modern web link and let users get more information, or even go inside.

Video: Aspen Interactive Movie Map, 1978-1981. Credit: MIT Architecture Machine Group

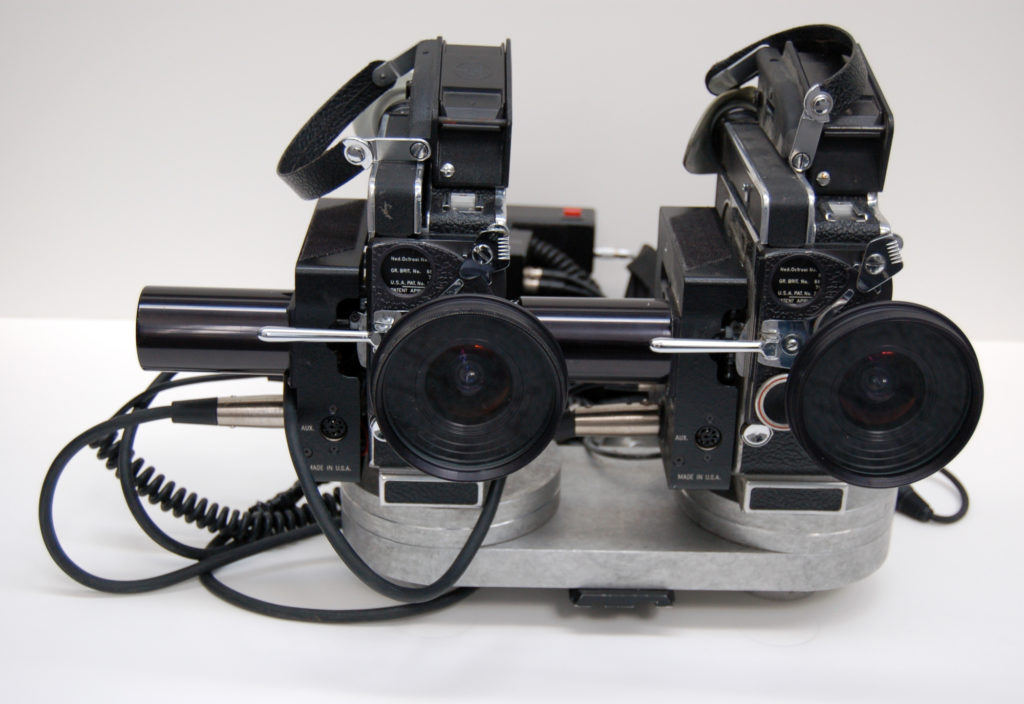

Michael Naimark making the “See Banff!” 3D movie map, 1994. Credit: Louie Psihoyos

To capture Aspen’s streets, project leader Andrew Lippman and cinematographer Michael Naimark customized a set of stop-motion animation cameras on a car’s roof to snap a full panorama roughly every 10 feet. Each shot was logged in a computer database. When the eventual user wanted to “move” a specific direction, the computer would call up the appropriate shot from the laserdisc player.

The Aspen Movie Map was ahead of its time. There were several efforts to start companies based on the technology, and a brief flowering of 1990s interest in computerized panoramas using Apple’s QuickTime VR (“Virtual Reality”). But street views remained mostly a niche product for art or the occasional display for tourists until the 2000s.

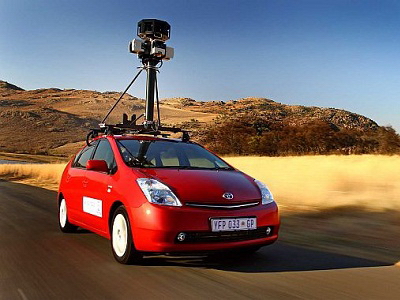

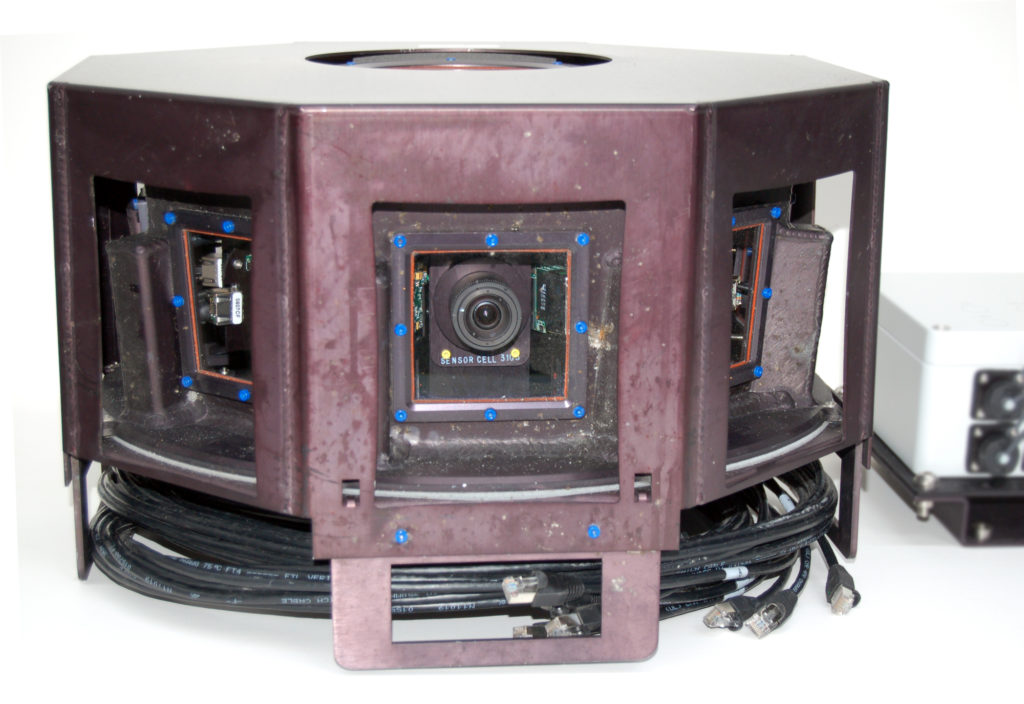

Early Street View van, with camera turret. The back was filled with equipment, now greatly miniaturized. Credit: Google Inc.

In 2003, Google co-founder Larry Page got intrigued with the idea of capturing street level views at massive scale. After shooting test footage with a video camera from his own car he funded a project at Stanford to develop techniques.

By 2005 Google had bought the companies that became Google Maps and Google Earth. Street View joined them in the same building, with Frenchman Luc Vincent coordinating the part-time efforts of a number of Googlers. The team experimented with high speed video cameras before settling on panoramic cameras like the early movie maps. The prototype van was filled with so much equipment it required a separate generator. The custom cameras were protected in an ominous-looking turret.

City8.com street view service in China

It all worked, in fact so well that the van quickly made itself obsolete. As soon as the company decided to go ahead with Street View at full scale, the custom installation was replaced with a more minimalist rig that could be quickly fitted to standard cars.

The service launched in 2007 as several other street view efforts were ramping up world-wide, including City8 in China, Everyscape in the US, and Location View in Japan.

Cheap computer power and storage had made street view services practical. Even more important, high-speed networking and the World Wide Web made them accessible. Early interactive movie maps required expensive custom equipment and high capacity data disks for each stand-alone user. By the mid-2000s, millions of people could realize the once-exotic dream of “surrogate travel” through an ordinary web browser.

Trike on a boat capturing the Amazon River. Credit: Google Inc.

Street View car in South Africa. Credit: Google Inc.

Hand cart in Iraq’s National Museum Louie Psihoyos

Beginning with views of four selected US cities in 2007, Google Maps with Street View has grown to cover major streets in over 39 countries, or more than five million miles of road, path, track, trail, and even museum hallway. It is the leading street view service world wide.

Local drivers work as contractors to Google all over the world, some logging tens of thousands of miles. For special projects, the company uses trikes, snowmobiles, hand-pushed carts, and even a backpack to map the paths and indoors spaces that cars can’t reach. Google planes have also started filming 3-D views from the air.

The hand-pushed Street View camera cart saw first use in 2009 at Iraq’s National Museum, which houses some of the world’s most important artwork and artifacts from early civilizations. The Museum was partly looted in the aftermath of the 2003 US invasion of Iraq.

Video: Luc Vincent, Director, Engineering, Google Inc. talking about the early days of Google Maps with Street View

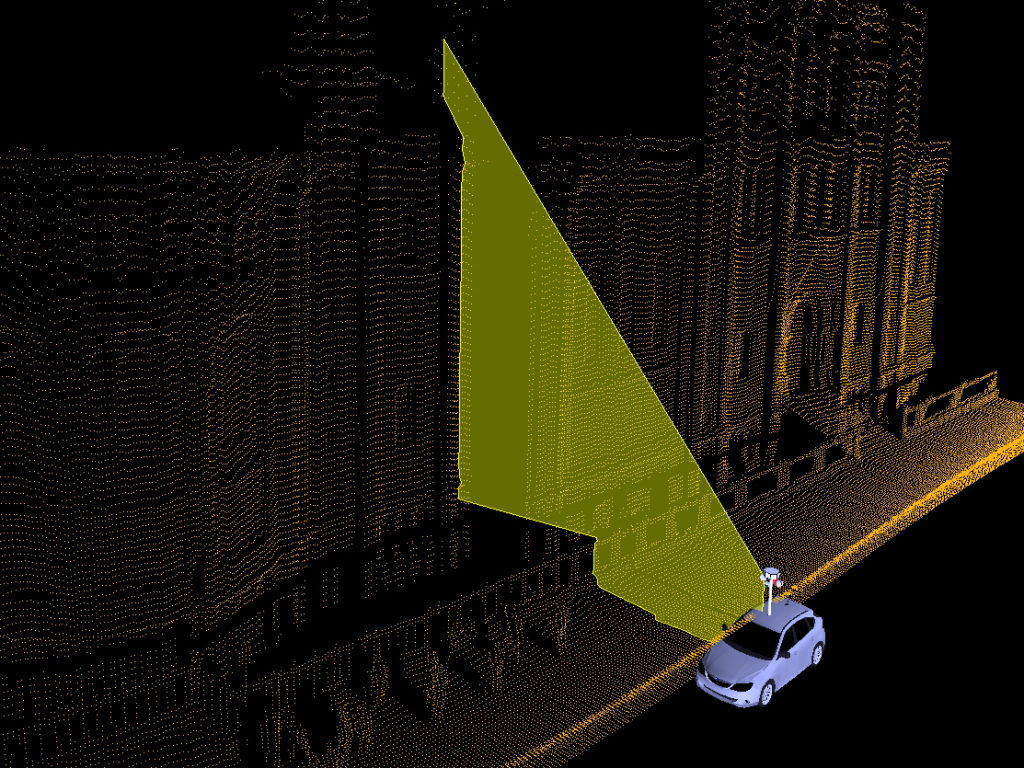

This photo illustrates some of the challenges of “stitching together” the separate images from each camera into a single, seamless panorama. Credit: Google Inc.

Like the original movie map projects, Google Maps with Street View drives cars equipped with roof-mounted camera clusters down streets. The driver checks reference shots on a screen, and can see both streets covered and those to be done on a moving map.

The panoramic cameras, now in their seventh generation, are tough and reliable. They take a set of pictures in every direction at known intervals, usually every nine to 15 feet. Beyond measuring the distance between shots, the cars use laser rangefinding, GPS, and image analysis to precisely determine the position of each picture and to later correlate it with Google Maps and Google Earth.

Street view uses laser rangefinding, GPS and image analysis for exact positioning. Credit: Google Inc.

After the camera’s hard disks are sent back to Google comes the hardest part – the processing that wasn’t cost-effective on a large scale until recent years. Custom software automatically “stitches” the separate photos taken together into a single panorama, and creates transitions between each set of pictures when you virtually move down the street.

The company also uses Street View to refine Google Maps. Special software analyzes the photos for readable signs and correlates them with the Maps database of businesses, street names, and house numbers.

Ladybug 2 camera assembly, 2008. Credit: Gift of Google Inc.

R5 camera, 2010. Credit: Gift of Google Inc.

Kea control box, 2009. Credit: Gift of Google Inc.

Stereoscopic 16mm camera assembly, from “See Banff!” 3D movie map, 1994. Credit: Loan of Michael Naimark

Street View now blurs faces and license plates in order to address privacy concerns. Credit: Google Inc.

We all know streets are public. But there’s a big difference between being seen in the moment or just by those nearby, and having your public self recorded and potentially seen by millions. This tension has been a part of street view projects since the 1970s. In response to both public and government pressure, many services including Google’s now blur faces and license plates automatically, and remove other things – from nudity to a sensitive military base – on request.

Privacy norms and laws also vary by country. Far more German households opt to blur their property than elsewhere. Japan limits camera height to avoid topping walls. Russia doesn’t restrict public photos, and nothing is blurred in street views by search engine Yandex.

Since Street View’s start, a number of websites have sought and shared sexy, humorous, and shocking images recorded by the roving cameras. A small percentage of these are staged, from mock fights to flashing: being recorded brings out the ham and the prankster in some people.

Ruins of ancient Pompeii on Google Maps with Street View. Credit: Google Inc.

After Google Maps with Street View toured the streets of Pompeii, the excavated Roman city that was buried with volcanic ash in 79 AD, real-world visits went up 30 percent. Similar stories hold for other attractions. Many people reflexively check the street view of a restaurant, apartment for rent, or new friend’s house before visiting in person. Most of us have looked at our own home online.

From armchair travelers to real estate agents to tax collectors, street views are subtly but deeply changing the ways we think about going places – and the facades we show to the world.

June 2008, Sendai, Japan, Google Street View photo before the earthquake and tsunami. Credit: MIT Architecture Machine Group

July, 2011, Sendai, Japan. Google Street View. photo following the earthquake and tsunami Credit: Google Inc.

Street views can also be an important public record; from information for new zoning, to helping rebuild more safely after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan.

Augmented reality (AR) brings the power of interactive maps to the real world as you experience it. Credit: Kevin Eisenmann

The first interactive movie maps go back more than three decades. What will the armchair traveler see 30 years from now?

Street views remains one of three very different ways of representing places: flat maps, three-dimensional models like those in games or Google Earth, and photographs of the world as it really appears like Street View.

The three are converging. As 3-D models get better, the artificial views they produce rival actual photographs. Conversely, Google and competitor’s technology for mapping street views onto three-dimensional models also improves.

Augmented reality promises to flip the whole process, and bring more and more computer-linked information to the real world as you walk through it.

Then there are historical views. People have long been fascinated with comparing the same scenes as they change over time, and computers can now automatically map photos to their place and viewing angles in the real world. So tomorrow’s street views may not only give us “surrogate travel” in space, but also in time.

What about video? Current street views are static, as if time had stopped. As video sources multiply, from CCTV to private smartphones, future services may bring in not only photos but also live feeds from all over the world.

Live feeds, of course, are a step in another direction. Most of the surrogate travel we’ve talked about is to a pre-recorded “place,” static and fixed. But our smartphones have already brought the ancient flat map alive with real-time updates on the location of our arriving Uber or Lyft rides. Now drones and the rare telepresence robot are becoming a part of our lives. This is the raw beginning of an entirely new dimension to surrogate travel — interaction.

So far, most of those interactions consist of somebody giving a buzzing drone the finger. But the genie is out of the bottle. Tomorrow’s armchair travelers will increasingly be able to not only see distant places, but to be part of them.

“Going Places: A History of Google Maps with Street View” exhibit was on display at the Computer History Museum from June 23, 2012 through August 2013.