This post coincides with the CHM exhibit, Deleted City (May 28–October 2016), and the September 21, 2016, live program, featuring GeoCities co-founder David Bohnett, with Deleted City artist Richard Vijgen.

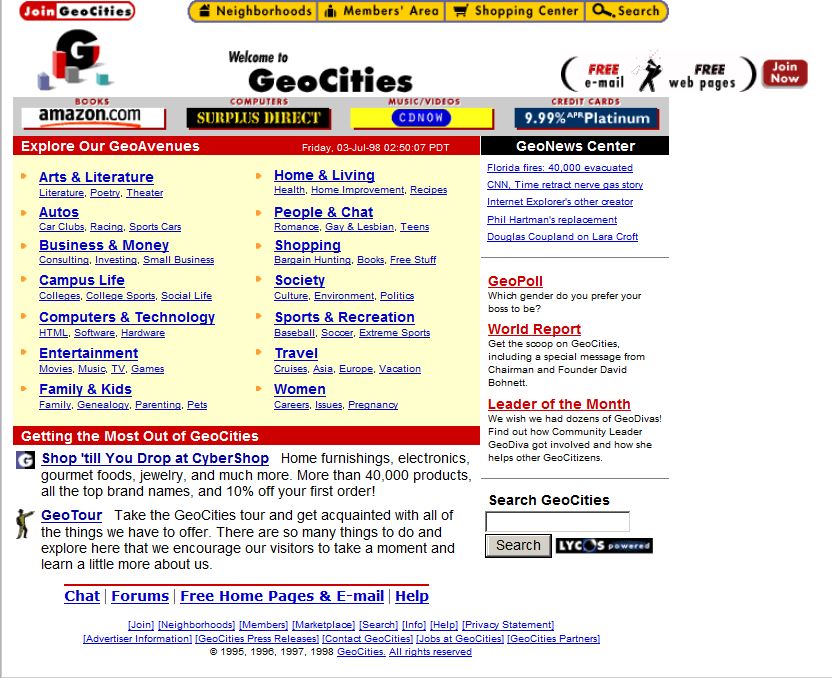

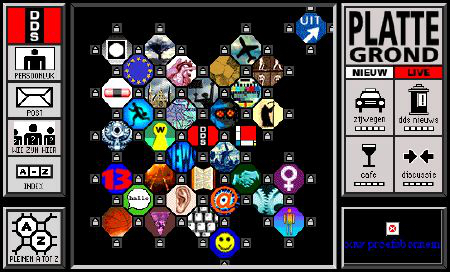

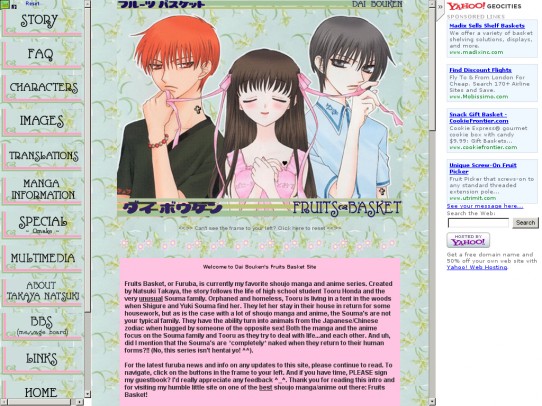

This cheerful welcome page greeted visitors to GeoCities in its 1990s heyday

In the very, very, beginning, the World Wide Web was meant to be a two-way medium. You could post and edit your own pages as easily as you could browse those created by others. But the browsers that made the web popular left out editing features.

That left a need. Only geeks knew how to turn raw HTML into pages. How could ordinary people put up their thoughts, pictures of their pets, the hobbies they wanted to share with the world?

Some commercial sites tried to fill the need. They offered users space on their servers and simple templates they could customize with their own thoughts, and pictures of their pets. The biggest and most colorful of these was called GeoCities.

Like CompuServe, PLATO, Usenet, and dozens of other online communities before the Web, GeoCities was organized by topic. There were “neighborhoods” for tech, and LGBT issues, and wine, and golf, and pages on anything and everything you can imagine.

The site grew like wildfire, along with the web itself. GeoCities was the third most visited place online in 1999. It would eventually reach 38 million pages—all created by users. That’s like one for every person in Canada!

On the eve of the dot-com crash, Yahoo! bought GeoCities for over three billion dollars. Ten years later, they shut down the US version of GeoCities after many users abandoned their properties for newer kinds of social networks. Much of the raw data was saved by unofficial archivists. That’s where the story of our summer exhibit begins.

Starting this spring the Computer History Museum was pleased to host “Deleted City,” an interactive art installation based on the surviving backups of GeoCities. It is an artistic answer to a question set to grow in importance, as more and more of daily life goes online: How do you present a digital ruin?

“Deleted City” and accompanying exhibit materials at CHM

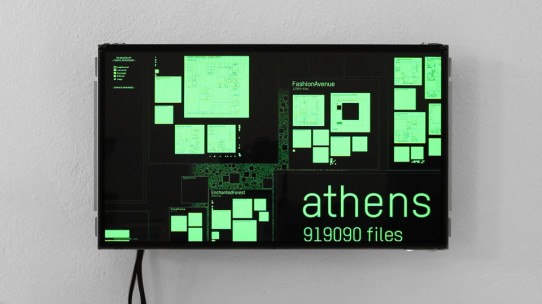

“Deleted City” is an interactive visualization created by Dutch artist Richard Vijgen of the 650-gigabyte backup of the early web hosting service and online community GeoCities. Vijgen’s “excavation” of the files that remain depicts the file system of the GeoCities backup as a city map, spatially arranging the different neighborhoods and individual lots based on the number of files they contain.

Vijgens chose this approach partly because so much of the user interface to the original GeoCities was lost. Today, the remains of the massive site are mostly raw files and a number of screenshots. It’s as if we saved many of the bricks and beams of a building, but not the assembled structure. As the web ages, future historians—and artists—will face such problems again and again.

In full view, the map is a data-visualization showing the relative sizes of the different neighborhoods. While zooming in, more and more detail becomes visible, eventually showing individual HTML pages and the images they contain.

A visualization of the digital map of Athens.

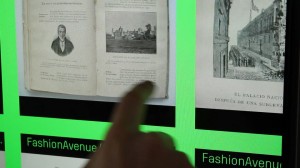

A visitor checks out the Fashion Avenue/Catwalk.

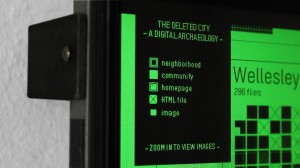

A key notes what icons represent different groups within the deleted city.

A visitor checks images within the Fashion Avenue/Catwalk area.

Richard Vijgen

Before CHM, “Deleted City” was on display at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The artist specializes in interactive data visualizations ranging from microscopic to architectural in scale. His work has been widely recognized by professional organizations and publications including Wired, Gestalten, the Smithsonian, Rhizome, The European Design Awards, and The Dutch Design Awards.

Danish artist Richard Vijgen discusses his approach to converting a 2-terabyte disk of GeoCities data into a work of art. View the entire CHM Live program below. * CHM Live program...

At CHM, the challenge of presenting “Deleted City” was framing it in such a way that visitors didn’t get confused between the art piece and the original GeoCities web site it is based on. We added a number of images and text panels around the installation itself to give context. There were three overlapping themes we wanted to touch on:

As some readers may know, CHM is about to launch a major exhibit Make Software: Change the World! on the social impact of software in January 2017, as part of a larger series of initiatives to collect and preserve this most basic stuff of the digital revolution. “Deleted City“ and the story of the partial resurrection of GeoCities serve as an informal preface to this larger theme.

In 1993 David Bohnett’s life was in pieces. His partner of 10 years had recently died after a prolonged struggle with AIDs. It was the peak of the epidemic, before the introduction of effective antiviral drugs. Bohnett stopped his work for a software company and moved to a small apartment in West Hollywood, traveling and trying to find a new direction. He had been an LGBT activist since graduate school. His partner Rand Schrader had been a prominent campaigner and among the first openly gay judges in California, appointed by Governor Jerry Brown during his first term.

On a plane flight Bohnett read an article about the World Wide Web, which was getting more and more serious attention from the technology press. He was an experienced user of social platforms including BBSs and the various Online Services such as Prodigy and AOL. Suddenly he knew what he wanted to do. As he told LA Weekly:

“I thought, ‘Let’s create something that takes the concept of interactivity and communication, and apply it to the World Wide Web.’ I was looking to throw myself into something.”

Using his life savings and funds from his late partner’s life insurance policy, he recruited web-savvy John Rezner, an IT manager at McDonnell-Douglass.

GeoCities co-founders David Bohnett and John Rezner. Tech entrepreneur and LGBT activist Bohnett wanted to help people interact on the Web. He teamed up with Rezner, a web-savvy computing manager at McDonnell-Douglas, and GeoCities was born.

Their web dream started small, as webcams showing a live stream of happenings at exciting places—one in the gay mecca of West Hollywood, another in Beverly Hills for high-end shopping. But when GeoCities invited users to add their own pages on those themes, they launched a virtual land rush.

The Digital City, Amsterdam, version 3.0. Amsterdam’s nonprofit, city-wide virtual community started in 1994. It helped inspire both other sites based on physical cities, and virtual landscapes like GeoCities.

In 1997 the site counted a million users, dubbed “Homesteaders.” The next year GeoCities went public at a value of $86 million; it was one of hot IPOs of an increasingly frenzied dot-com boom. Bohnett used the money to add a number of features including a search engine and an evolving set of tools and templates which made it increasingly easy to create your own pages—no HTML skills required. Social tools made it easy for users to interact. Besides personal pages there was also business hosting, world news, shopping, and more.

By 1999 GeoCities was the third most-visited site on the web. There were 41 theme-based neighborhoods, ranging from fan fiction to fine dining. Its now tens of millions of users had populated neighborhoods such as WallStreet for investing and finance, Baja for off-roading, Athens and Acropolis for education and philosophy, EnchantedForest for kids, Heartland for hometown values, and so on.

From the community’s business potential to the webcams that gave rise to one of the most popular internet sites in the ’90s, David Bohnett shares stories from GeoCities’ early days. View the entire CHM Live program below. * CHM Live program..

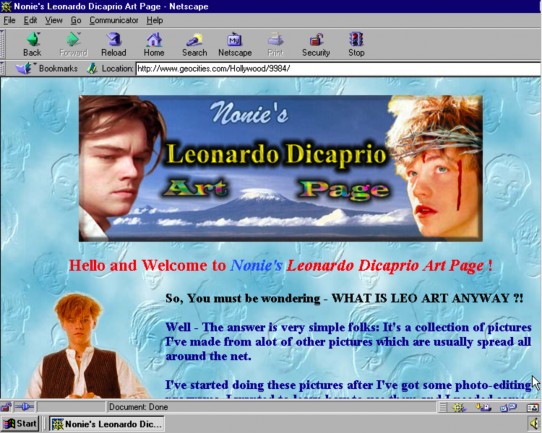

“Leonardo DiCaprio” fan page in Hollywood

Modifying images is older than Instagram. This fan used photo retouching software to play with various images of Leonardo DiCaprio.

“My Cats” page in Petsburgh

Cats have been online for a long time. Petsburgh was the GeoCities neighborhood for everything to do with our animal companions.

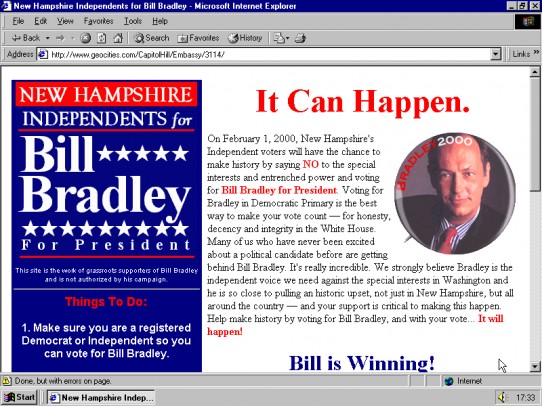

Political page on CapitolHill

Although email played a role in the ’92 US presidential campaign, by 2000 the web had become a new mass medium, complete with ads. CapitolHill was the place for all things political.

Anime fan page in Tokyo

Fan pages of various kinds were a staple of GeoCities. Tokyo was the neighborhood for Far East topics, including anime.

Bohnett’s timing for launching a web business had been perfect. So was his timing for getting out. In 1999 Yahoo! bought GeoCities for over $3.5 billion. Bohnett’s share of the sale launched his career as a major philanthropist, with a focus on LGBT and tech education causes. The dot-com bust battered Yahoo!, but it survived along with the GeoCities community.

By the early 2000s a new kind of online community was taking off. The focus of sites like Myspace and Facebook wasn’t general topics, like Beagle owners or punk rock. Their focus was you, the user—and your connections to your friends. The modern social media boom was under way.

Yahoo! eventually decided GeoCities was obsolete. All 38 million pages of the main English-language site were set to be erased in October 2009.

Half a dozen unofficial efforts, notably the Internet Archive as well as Jason Scott (pictured above) and Archive Team, managed to mirror substantial portions of GeoCities before its 2009 termination by owner Yahoo.

Before that happened, though, several groups of hacker preservationists stepped in. Volunteers at the Internet Archive and Archive Team preserved tens of millions of pages. You can find most at the Internet Archive, by searching or from their GeoCities archive.

Yahoo’s GeoCities Japan subsidiary is still thriving today.