Before 1975, the computer was an exotic and expensive tool for engineers, scientists, and businesses. By 1985 the computer had been “democratized”, and anyone with the need, the interest, and a few thousand dollars could have one of their own.

At the nexus of that remarkable ten-year transition was the San Francisco Bay Area’s “Homebrew Computer Club”, an informal gathering of designers, hackers, entrepreneurs, and hobbyists who were early participants in the personal computer revolution.

The first meeting was on March 5, 1975 in a Menlo Park garage. Thirty-eight years later, on November 11, 2013, the Computer History Museum hosted a reunion organized by Hilda Sendyk, Lee Felsenstein, and Joel Franusic. Many of the club members were present, and some brought their still-running vintage computer gear.

Featured on this video of the 2013 reunion are longtime club moderator Lee Felsenstein, keynote speaker Ted Nelson, Apple Computer co-founder Steve Wozniak, and others.

In 1975 I was a Computer Science graduate student at Stanford University, working hard to avoid completing my PhD thesis. I spent much of my time at SLAC, the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, where we started a “Microprocessor Lab” to investigate how to replace the expensive custom hardware used in high-energy physics experiments with the new inexpensive microcomputer chips that had just been invented by Intel and others.

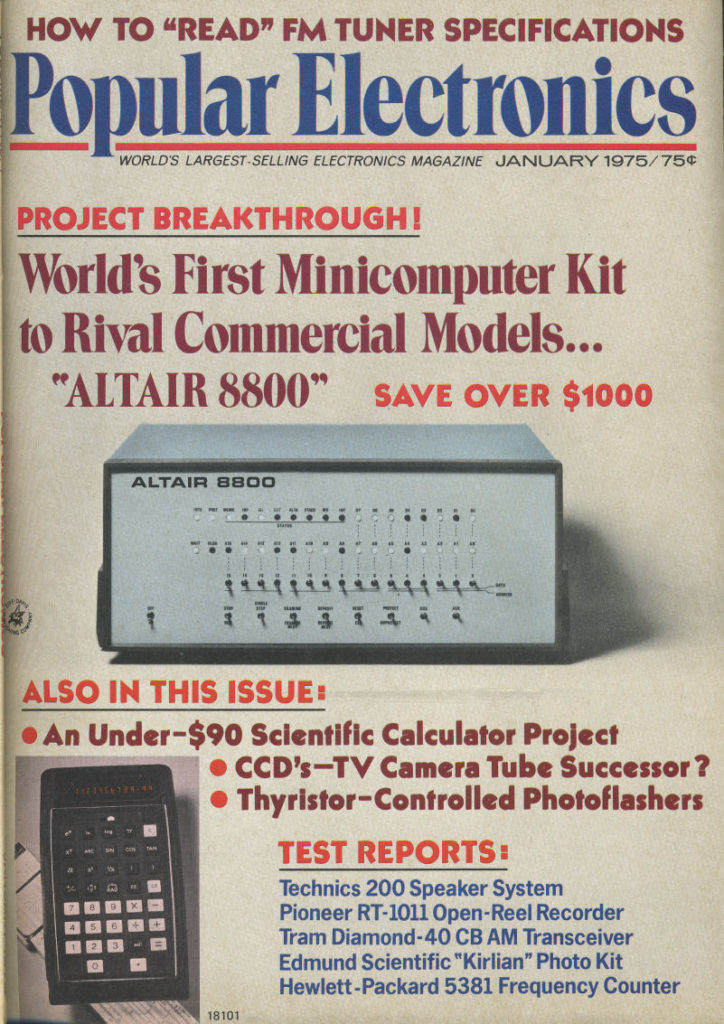

Popular Electronics, January 1975

In January of 1975, the cover of Popular Electronics featured the Altair 8800, a new inexpensive personal computer kit from MITS, an obscure company in New Mexico. Based on the latest Intel 8080 microprocessor, it offered the opportunity for any propeller-head with a soldering iron to have their own computer for only $439. Expecting to sell only a few hundred, they booked thousands of orders in the first month.

Two of those orders, among many from the Bay Area, were from us at SLAC. Another was a review unit sent to a loose-knit organization of computer enthusiasts, the People’s Computer Center in Menlo Park. When their unit arrived in March, Gordon French and Fred Moore posted flyers around town, inviting people to come to Gordon’s garage to see the Altair and the other home-built computers that people were working on.

I was one of 32 people in Gordon’s garage that rainy evening. We introduced ourselves, explained our interests and activities, and argued about everything from which was the best microprocessor chip to the virtues of octal vs. hexadecimal notation for coding computer instructions. Six people had already built their own computers, and almost everyone else wanted to.

It was clear that there was enough interest to have more meetings. After trying a couple of other locations, Frank Rothacker (a SLAC staff member) and I arranged for the group to meet at SLAC, which became the club’s home for many years.

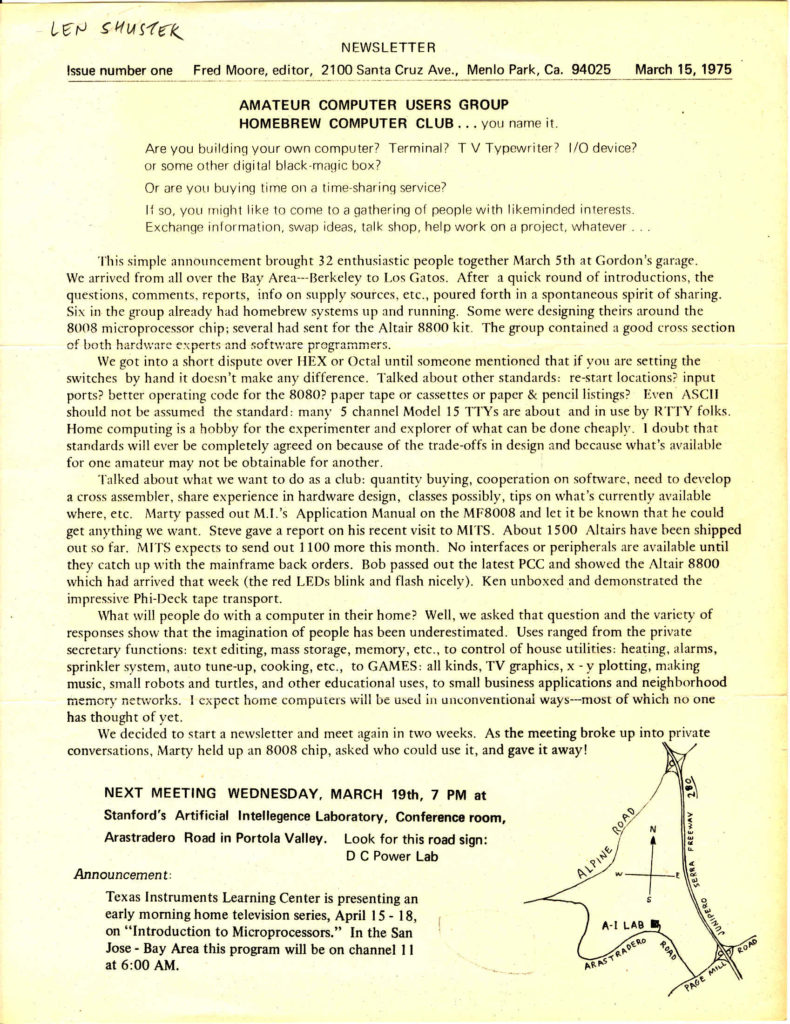

The first Homebrew Computer Club newsletter, March 15, 1975

Gordon French, a programmer with military security clearance, chaired the first three meetings. Co-founder Fred Moore, a counter-culture political activist and community organizer, wrote the newsletters. The club made for strange alliances.

Soon Lee Felsenstein, who was more entertaining and encouraging of group participation, took over as the master of ceremonies. He divided the time into the “mapping period” when people would publicly talk about what they were working on, had to give away, or needed, and then the “random access period”, where people milled about, found people they wanted to talk to, and exchanged information, hardware, and software.

Proud builders would often set up card tables in the anteroom to the SLAC auditorium to show off their latest creations. More often than not, they would share the complete details of what they had done.

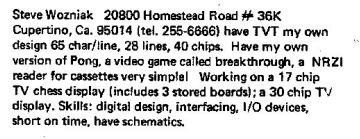

Steve Wozniak did that with his Apple I, and although every engineer admired the brilliance of his design, there were few who could have predicted that it, and not the computer on the next card table, would be the seed corn of a major successful company.

Note in the second club newsletter, April 12, 1975

SLAC really didn’t know what they had gotten into, but they were pretty tolerant. One rule they had to enforce, because they are government-funded, is that no commercial business take place there. So the buying and selling moved into the parking lot of the adjacent Sharon Heights shopping center, which was not as tolerant and complained to me and to SLAC. After the meetings, a subset of the participants continued the buzz into the night at the Oasis Beer Garden in Menlo Park.

Homebrew Computer Club meeting in the SLAC auditorium

There are only a few photographs and almost no video of the biweekly club meetings. The only extensive contemporaneous records are the wonderfully chatty Newsletters that were edited initially by Fred Moore, and then by Robert Reiling starting with the 6th issue in August 1975. You can see many of them here:http://www.computerhistory.org/collections/catalog/102740021.

This free-spirited gathering of enthusiastic hobbyists was the advanced guard of a revolution that had two aspects:

– Establishing that microcomputers were a cheaper and better way to do computing. The big computer companies were, generally, making the mistake of treating microprocessors like toys instead of the next generation of computers. Homebrew club members showed what could be done with them, and that they really were the next wave, not just a sideshow.

– Advancing the “democratization” of computers. Suddenly everyone could have one.You could argue that Homebrew, and the companies and products that the people who went there built, created the personal computer revolution. Now that’s a small exaggeration, because it would have happened anyway. But I do think that the open sharing of information that went on at Homebrew was a catalyst that made it happen sooner.

In his 2005 book “What the Dormouse Said”, John Markoff says “The Homebrew Computer Club was fated to change the world… At least twenty-three companies, including Apple Computer, were to trace their lineage directly to Homebrew.”

For me the most inspiring moment of the 2013 reunion was when organizer Joel Franusic asked “How many of you were not yet born in 1975 when the first club meeting was held” and half the people in the audience raised their hands. The baton is being passed to the next generation, this time fueled by inexpensive computer boards like Arduino and Raspberry Pi, with their easy control of robotics and interconnection to the web.

The revolution isn’t over.