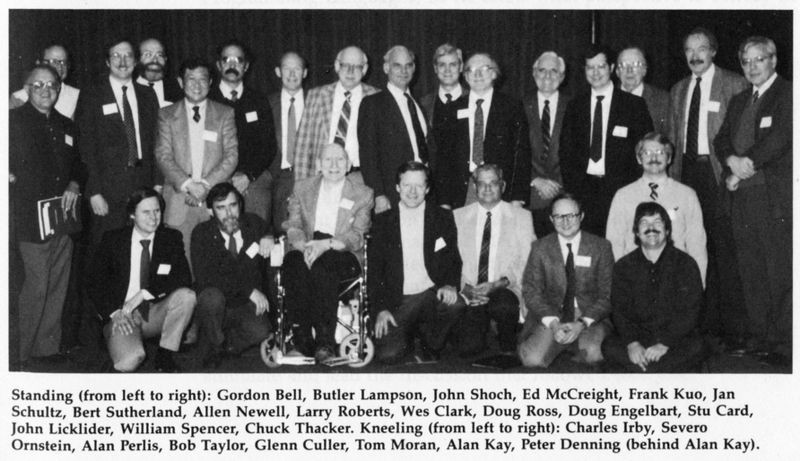

On January 9th and 10th of 1986, at Rickey’s Hyatt House in Palo Alto, California, there was an historic gathering of the pioneers who invented personal computing. The event was sponsored by the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM), and hosted by the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC). Called the “ACM Conference on the History of Personal Workstations”, it was chaired by Alan Perlis of Yale University and organized by John White of PARC. The speakers were a “who’s who” of innovative computing, including Allen Newell, Gordon Bell, JCR Licklider, Larry Roberts, Doug Engelbart, Alan Kay, Chuck Thacker, Butler Lampson, Wes Clark, and others. If you were lucky enough to have been there, you were a witness to a remarkable event.

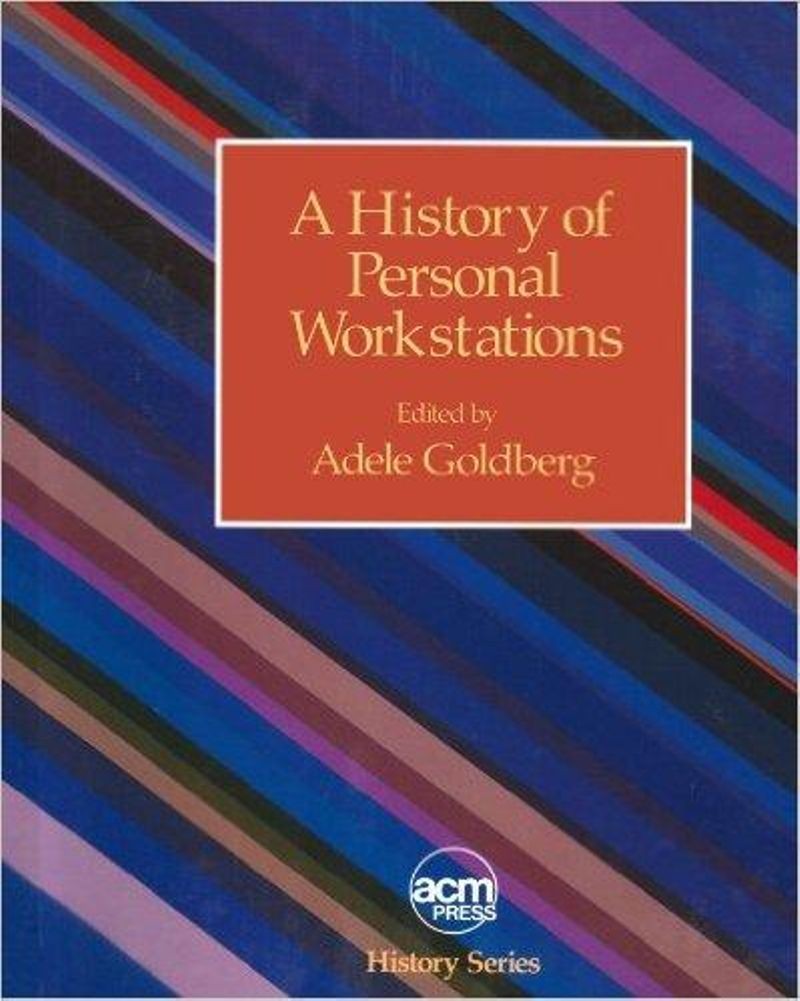

The papers submitted to the conference were first published as a Proceedings by the ACM. They were later edited by Adele Goldberg of PARC and published in 1988 as the first book of the new ACM Press History Series 1. As Adele said in the preface, “The history of computing is especially affected by the visions of a few people… This book about a history is dedicated to the people who invented the personal workstation.”

As wonderful as the book is, a carefully edited manuscript or transcript is very different from a live performance. The presenters did not just read their papers. They told stories, they acted, they expressed emotion, and they made predictions. Fortunately, most of the performances were videotaped, and several copies of the set of tapes were made.

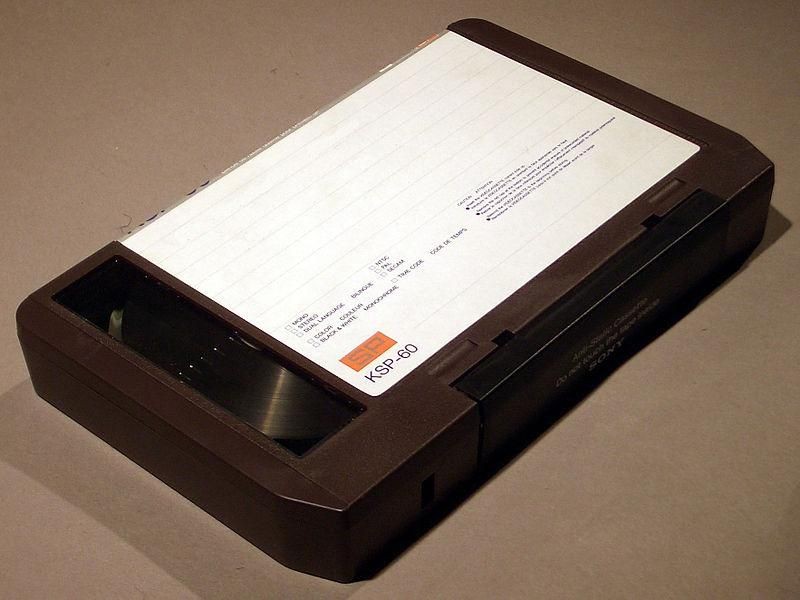

The recording medium was a ¾” magnetic tape analog cassette called U-matic, a now-obsolete format that was developed by Sony before Betamax or VHS. We don’t know how many sets of conference tapes were made, or how many have survived, or how many are still readable. ACM and PARC have apparently lost track of their copies. Luckily our predecessor, The Computer Museum in Boston, kept theirs, and it became part of the Computer History Museum’s collection. But could the tapes be read? After 30 years videotape degrades because of hydrolysis of the polyurethane binder that holds the magnetic particles. Some tapes of that age are completely unreadable. In this case we were lucky. With financial support and permission from the ACM, CHM has successfully read and digitized its ageing cassettes of that conference. We are pleased to now make them available on the Museum’s YouTube channel here.

In his “Introduction to the Conference”, John White described its structure: “There were 13 presentations over the two days of the conference. Each presentation was an hour in length, except for Alan Kay’s two-hour banquet talk. In addition, each speaker was introduced by an individual that was a part of the history being reported. These ‘discussants’ helped stimulate and lead the discussion that followed each talk.”

Here are the sessions, introducers, speakers, and links to the specific videos. The last two columns contain links into the ACM Digital Library to the paper that was submitted to the conference, and to the chapter published in the book several years later. These have recently been made publicly available for free, thanks to Pat Ryan and Wayne Graves at the ACM.

The Licklider and Englebart talk videos are lower quality because they had to be digitized from VHS tapes instead of U-matic cassettes. We are grateful to Yoshiki Ohshima of Alan Kay’s Viewpoints Research Institute for doing that; he also digitized an amusing video that was prepared at the time from the outtakes of the filming.

Here are very short descriptions of the talks captured by the videos. Perhaps they will intrigue you enough to want to view more. Many of the presenters illustrated their talks with slides and films, and it is a tribute to the videotape producers and editors Kenneth Beckman, Adele Goldberg, and Gloria Warner at PARC that so much of that collateral material was well captured on the video.

As always, Gordon positioned a narrow topic in the larger field of its encompassing history. He showed how workstations fit in the evolution of computer classes, and reported Alan Kay’s prodding him that “We’ve got to hold this conference because workstations are going to disappear”.

Unlike his written paper, Doug Ross’s live presentation took a chronological view of the history of personal computing, as he experienced it, starting with his own first exposure to software in 1952. He had extensive experience using MIT’s Whirlwind as a (very expensive!) personal computer, and tells wonderful stories about writing and debugging programs on that and other first generation machines.

In this wide-ranging talk, the visionary “Lick” covers the history and future of computers, input and output devices, and the user experience. He describes, with tongue firmly in cheek, “How I invented the workstation.” Here’s his prescient take on how input should be done.

He muses on the evolution of software as a product, and the need, in some cases, for what we have come to know as “open source” products.

ARPANET program manager Larry Roberts began his computing career at MIT on 1958 using the TX-0 as his personal workstation. “I used 759 hours of computer time personally on the TX-0 during that year.” He then graduated to the TX-2.

He then describes the origin and evolution of the ARPANET as “what was next” after timesharing, except that “nobody was excited” about the idea of networking for sharing computers or data.

Culler describes his work at the University of California in the 1960s on interactive systems for mathematical analysis. But even by 1986 he was disappointed in what could be done: “If you want to do interactive computing where you see the results in mathematical transformations, there isn’t a supercomputer in the world that can keep up with you – yet. Technology is still developing”.

Engelbart describes his lifelong quest for computer systems that augment human abilities, and how he embarked on that mission early in his career.

He shows excerpts from the famous 1968 demo of his NLS (oN-LineSystem, later Augment) that introduced many concepts we now take for granted. He also takes us behind the scenes, explains how difficult and risky that demo was, and says it was successful “because Bill English is a genius.”

Alan’s dinner speech started by observing that no one at the conference had a computer with them. How that would be different today!

In discussing the original conception of the Dynabook, he noted how important networks turned out to be: “They change the whole environment that you’re in; they don’t just hook environments together.”

Thacker was responsible for much of the distributed personal computing system hardware created at Xerox PARC, including the groundbreaking Alto. He talks about the bitmapped display and the communication network as the most important aspects. He, like Alan before and Butler Lampson later, gives insight into the environment at PARC, and pays tribute to Bob Taylor as “probably the most brilliant research manager on earth today.” He describes the details of the designs they produced. He ends with the prediction that workstations were not going to disappear, but would morph into what would be used by a much wider community.

Lampson points out that unlike the hardware, and unlike software systems like Smalltalk, the Alto software was big and complicated.

He describes the design of the software, and how their goal was a very practical step towards a larger grander vision that wasn’t achievable at the time.

Wes Clark was the principal architect at MIT of the TX-0, TX-2, L-1, ARC-1 and, with Charles Molnar, the LINC, a groundbreaking small laboratory computer. In his very amusing talk, full of anecdotes about other pioneers, Wes describes what the constraints were.

One of those constraints was that users were biological researchers, not computer engineers.

Chuck started at HP in 1962, and so witnessed the development of both calculators (the first was priced at $4900!) and computers at what had been a manufacturer of electronic instrumentation primarily for the communications industry. During the talk he describes the evolution of those products, and also speculates on the eventual “disappearance” of computers as they become part of the fabric of society.

He also tells the story of “Bill Hewlett’s favorite project”, the shirt-pocket-sized scientific calculator.

The Problem Oriented Medical Information System (PROMIS) was developed by Jan Schultz and Larry Weed at the University of Vermont. “We’re really looking not at automating offices, but at automating companies. In our case, the company was a hospital. … Like Butler Lampson, we are interested in interaction rather than programming for the users of our system.” The did this with a distributed network of minicomputer nodes, to which many specialized touch-screen terminals were attached.

The last talk at the conference was more about psychology than technology. Card and Moran worked at Xerox PARC on the human interaction with personal computers. In their talk they describe their study of methods of pointing, typing, editing, menu navigation, and the mental models that users create.

As you can see, the conference documented a wide range of topics about personal workstations, in part motivated by the fear that they would disappear and take their history along with them. Indeed they have disappeared, only to have their ideas resurface, in even better form, in today’s laptops, tablets, and phones. And thanks to the conference, we have their history too.