So begins one of the earliest chapters in the life of two remarkable young men whose youth, energy and enthusiasm transformed the world.

The “Blue Box” was a simple electronic gizmo that bypassed telephone company billing computers, allowing anyone to make free telephone calls anywhere in the world. The Blue Box was illegal, but the specifications for hacking into the telephone network were published in a telephone company journal and many youngsters with a flair for electronics built them. The “two Steves” had a great deal of fun building and using them for “ethical hacking,” with Wozniak building the kits and Jobs selling them—a pattern which would emerge again and again in the lives of these two innovators. (Wozniak once telephoned the Vatican, pretended to be Henry Kissinger and asked to speak to the Pope—just to see if he could. When someone answered, Woz got scared and hung up.)

Wozniak and Jobs Blue Box, ca. 1972. The Blue Box allowed electronics hobbyists to make free telephone calls. CHM #X727.86

These early playful roots are what Wozniak remembers most fondly of Jobs. As columnist Mike Cassidy recalled in a San Jose Mercury News interview, what these two friends most remembered was “not bringing computers to the masses … or the many ‘aha’ moments designing computers. Instead, it’s the time the two tried to unfurl a banner depicting a middle finger salute from the roof of Homestead High School…” or their many Blue Box exploits. Walter Isaacson, Jobs’s official biographer, cites Jobs reflecting on the Blue Box:

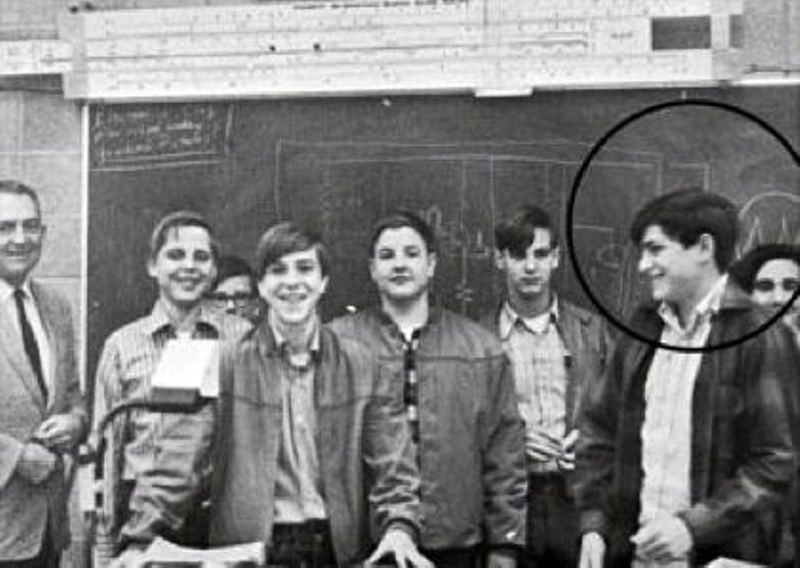

Steve Jobs (circled) at Homestead High School Electronics Club, Cupertino, California ca. 1969

Jobs, like Wozniak before him, attended Homestead High School in Cupertino, California, a solidly middle-class school in the suburbs of Silicon Valley. Homestead was progressive, with an innovative electronics program that shaped Wozniak’s life. Jobs and Wozniak had been friends for some time. They met in 1971 when their mutual friend, Bill Fernandez, introduced then 21-year-old Wozniak to 16-year-old Jobs. After hours, the two Steves would often meet at Hewlett-Packard lectures in Palo Alto, and both were hired by HP for a summer. Jobs graduated high school in 1972 and attended Reed College in Portland, Oregon for a semester, during which he collected Coke bottles for money and ate free meals at the local Hare Krishna temple. After drifting from class to class, Jobs left for India on a spiritual quest with Reed College friend Dan Kottke (who later became Apple employee #12). Jobs returned as a Buddhist and in 1974 began working at the legendary gaming company Atari as a technician.

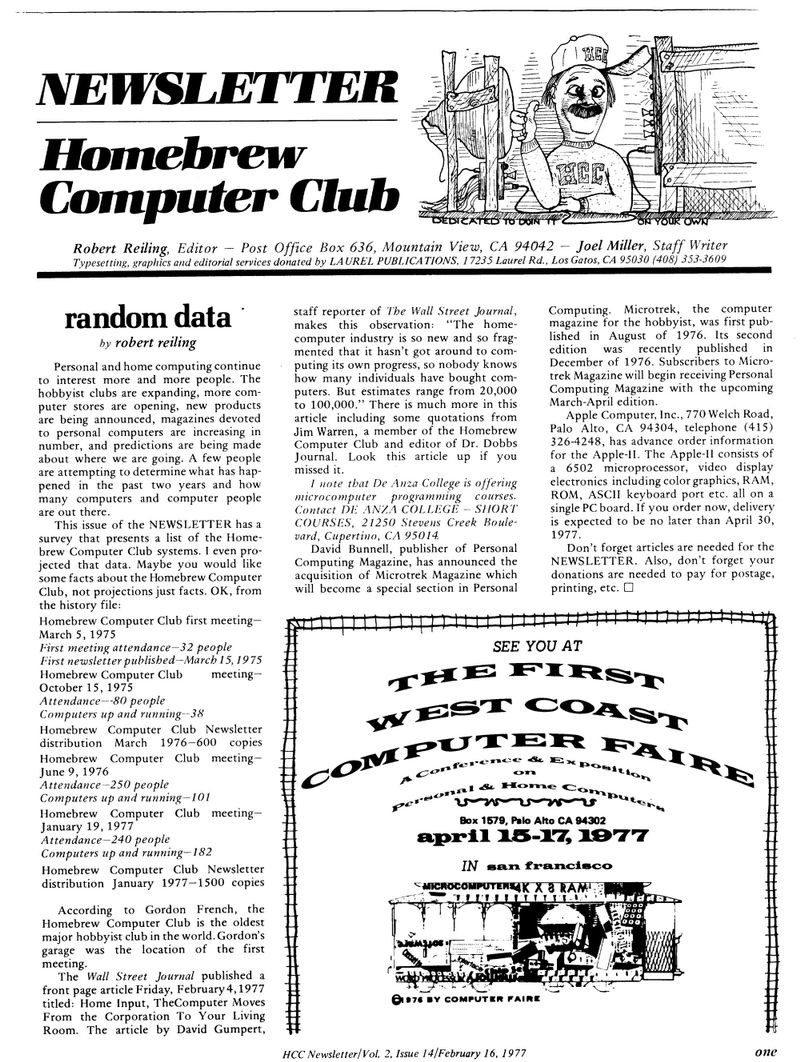

The Homebrew Computer Club newsletter was a forum for hobbyists to exchange information and ideas.

The next year, Jobs began attending meetings of the Homebrew Computer Club, a group of electronics and computer hobbyists in Silicon Valley who got together to explore the latest in a new technology, the microcomputer.

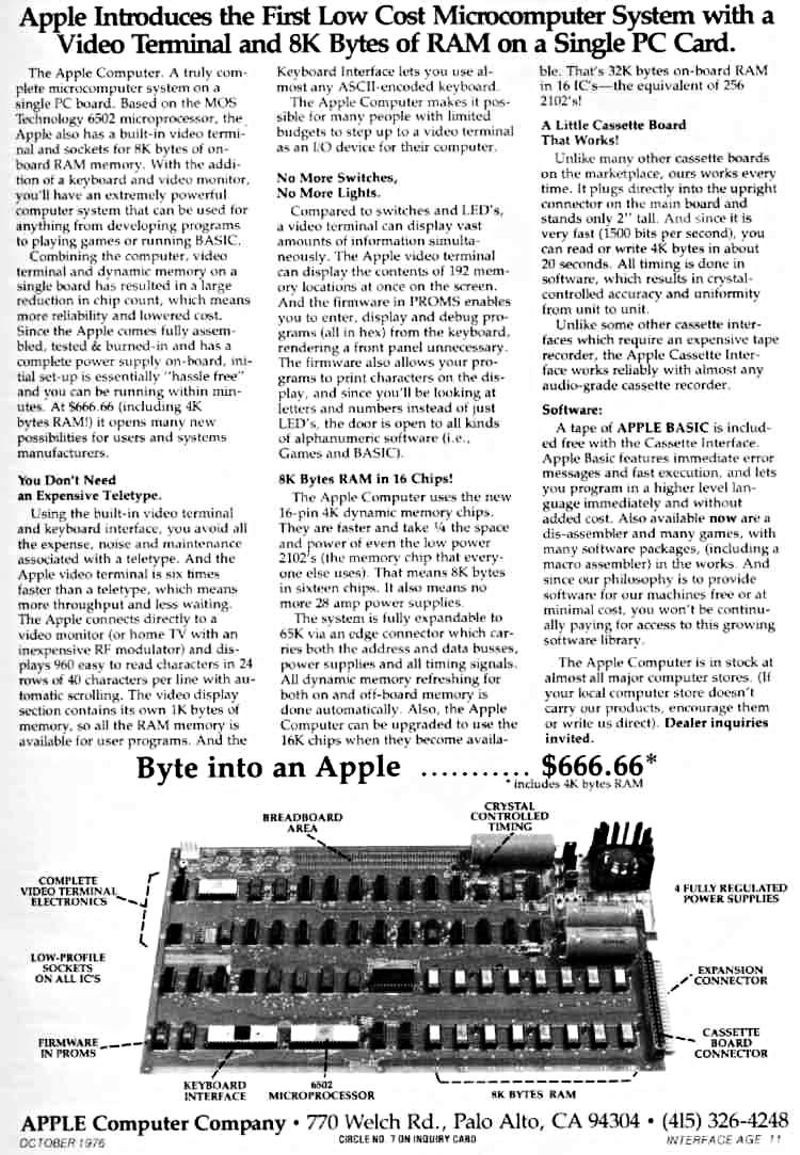

Wozniak, who had no formal engineering training, designed the Apple-1 computer as a way of “showing off” to the people at the Homebrew Club. Based on an inexpensive 6502 microprocessor, the Apple-1 came as a kit and was aimed squarely at hobbyists who wanted to own their own computer, even if they weren’t quite sure what they could do with it. The Apple-1 was a masterpiece of circuit design and its elegance impressed all who could appreciate its simple but powerful conception. Ever the salesman, Jobs quickly appreciated that there might be a demand for the Apple-1 beyond the geeky members of the Homebrew Club. Jobs showed an Apple-1 to Paul Terrell, owner of the local Byte Shop computer store, who placed an order for 50 of the machines—so long as they came pre-assembled. To obtain funds to purchase parts for the Apple-1, Jobs had obtained 30 days’ credit from suppliers—just long enough to enable Wozniak and Jobs to build the computers (mostly in Jobs’s parents’ garage) and get paid for them. To fund the circuit board layout of the Apple-1, Wozniak sold his beloved HP-65 calculator and Jobs his Volkswagen van. The Byte Shop order brought in $50,000, a “total shock” to Wozniak, who was earning one-tenth of that as an engineer at HP. The sale spurred Jobs into thinking about a new computer that anyone—not just those handy with a soldering iron—could afford and use.

Homebrew Computer Club meeting, 1978 Courtesy of Lee Felsenstein

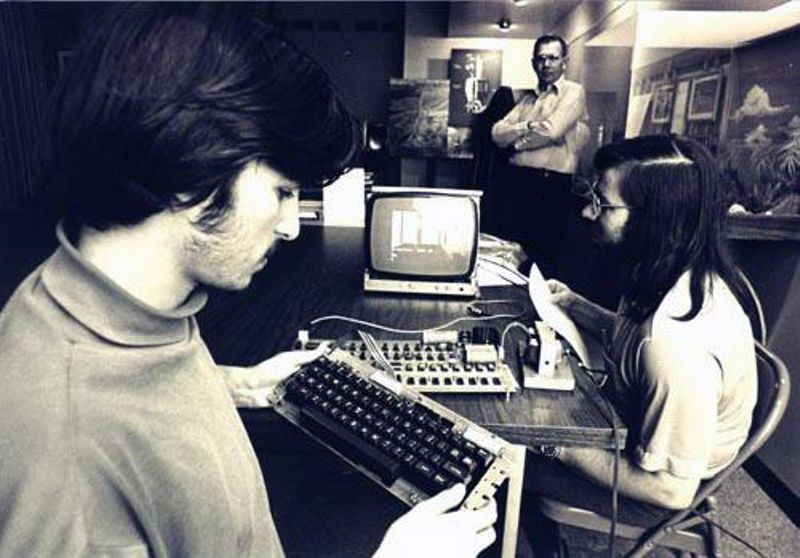

Steve Jobs and Wozniak using Apple-1 system, ca. 1976 ©Apple, Inc. / Joe Melena

The Apple-1 kit computer introduced in 1976 Photo: ©Mark Richards

Early ad for the Apple-1 computer system, ca. 1976

Funding this vision presented some challenges: the idea of people having their own computers was viewed as absurd at the time. Banks were unwilling to loan the two Steves money. After several unsuccessful visits with venture capitalists, Jobs met Mike Markkula, who, at 32, was already retired from Intel. Markkula was an electrical engineer with solid management skills who would provide “adult supervision” to the young company as well as something else: he personally invested $250,000. The three founded Apple Computer in January, 1977.

The original Apple II personal computer, the machine that propelled Apple into a global company (1977) Photo: ©Mark Richards

Jobs and Wozniak immediately moved forward with their new machine, the Apple II. It was a big improvement over the Apple-1. It had an integrated keyboard and case, could plug into a TV set for display, and was ready to run right out of the box. It also had color graphics, which made it unique among similar computers at the time such as the Radio Shack TRS-80 and the Commodore PET. It was a consumer item, not a kit for hobbyists.

If the Apple II featured typically brilliant Wozniak design, the marketing was vintage Jobs. This was Apple’s first mass-produced product, and Jobs sold it as a computer for everyone, from students to business professionals. The Apple II’s success was unprecedented, in part because, under Markkula’s urging, Apple donated or gave huge discounts to schools—ensuring that a new generation of students would learn about computers on an Apple. But the Apple II also enjoyed a business windfall with the arrival of the spreadsheet program VisiCalc in 1979. Powered by demand from both the education and business markets, Apple II sales soared. The Apple II would live on in various models until 1993—an astonishing 16 years. Early chants of “Apple II Forever” among the Apple faithful rang long and clear.

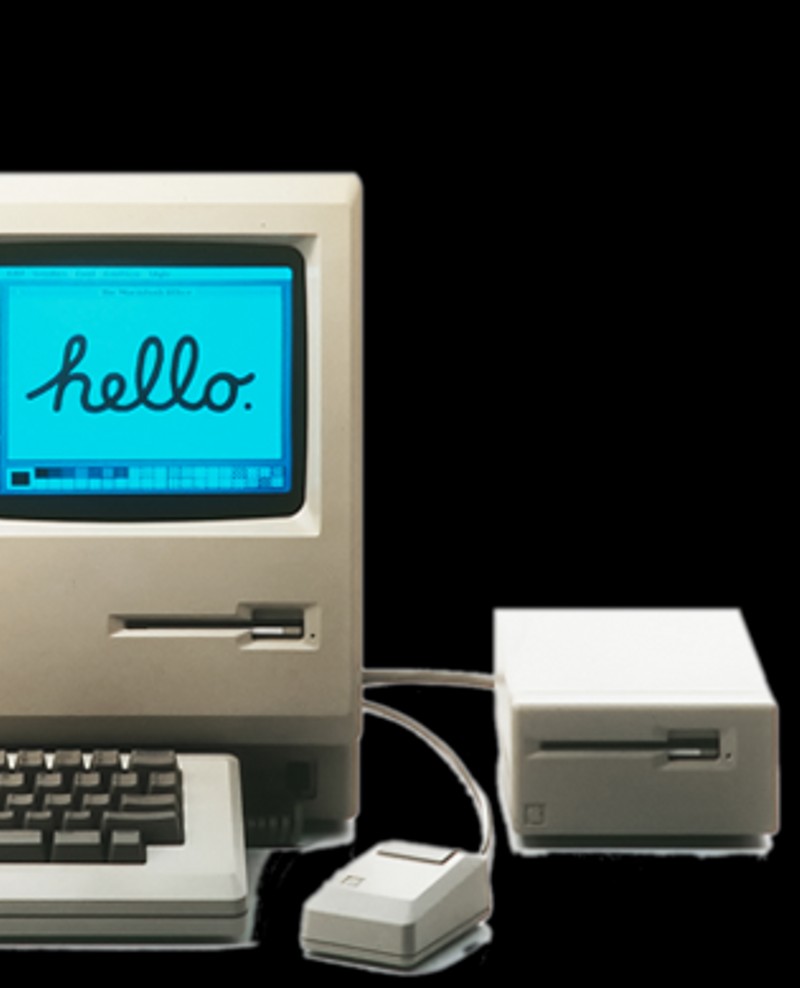

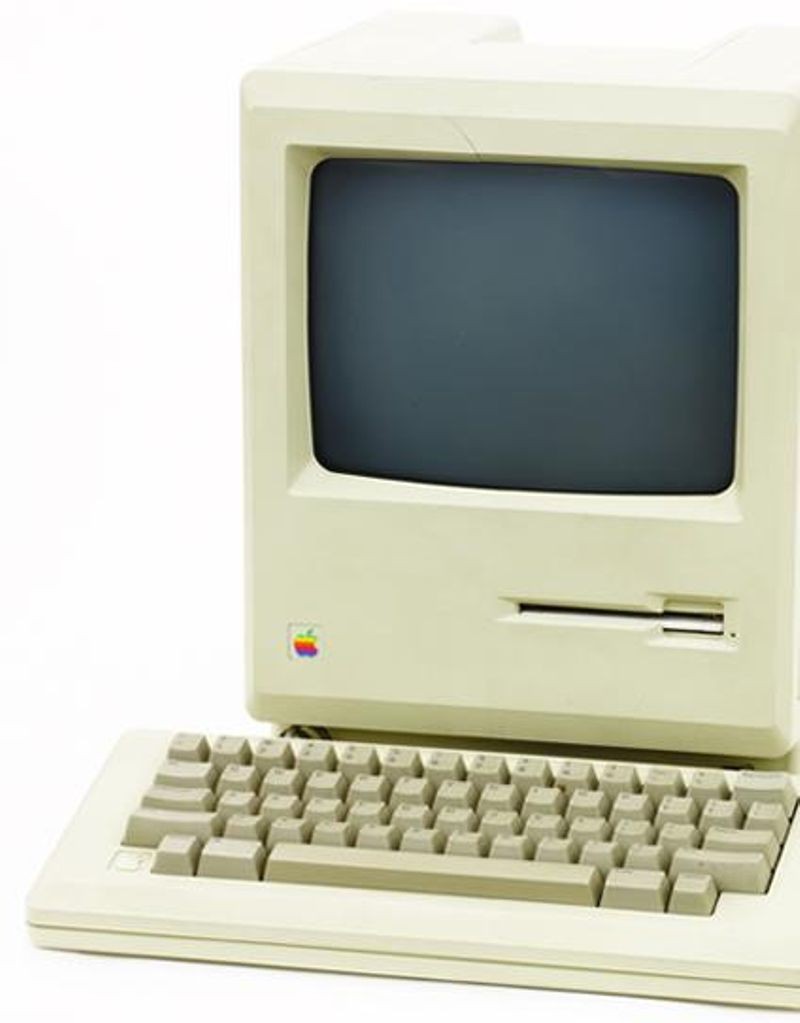

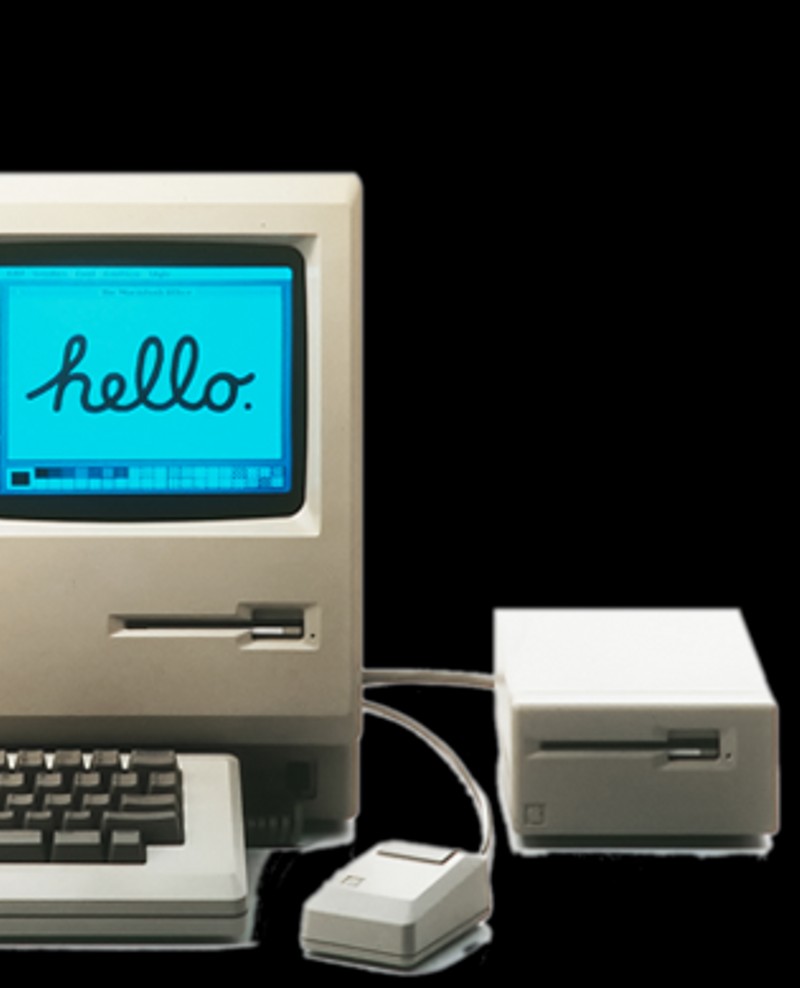

Apple Macintosh, 1984. The Mac revolutionized personal computing by introducing the graphical user interface (GUI), allowing anyone to use a computer CHM# 102633564 Photo: ©Mark Richards

Jobs’s greatest triumph, however, was the 1984 Macintosh, “the computer for the rest of us.” Macintosh offered users an entirely new way of interacting: the graphical user interface (GUI). No longer would people have to learn special commands or have specialized training to use a computer. Now everyone who could point and click a mouse (even children) could run a computer. The Macintosh kicked off a new personal computer revolution, one that stressed intuition and use of a common graphical look and feel over memorization of computer codes.

Apple launched the Macintosh with a revolutionary television commercial produced by science fiction filmmaker Ridley Scott. The commercial aired only once—during the 1984 Super Bowl broadcast. Even with its splashy introduction and its breakthroughs in usability and design, however, the Mac started slowly in the marketplace and sales were modest in the first year. Moreover, Jobs’s intense personality, drive for perfection and difficult management style frequently clashed with others at Apple. In 1985, he suffered the same fortune as many Silicon Valley founders: he was fired by the board of directors. Jobs’s departure marked the end of an era and the beginning of a period of massive hits and equally big misses for him. That period would last for a decade.

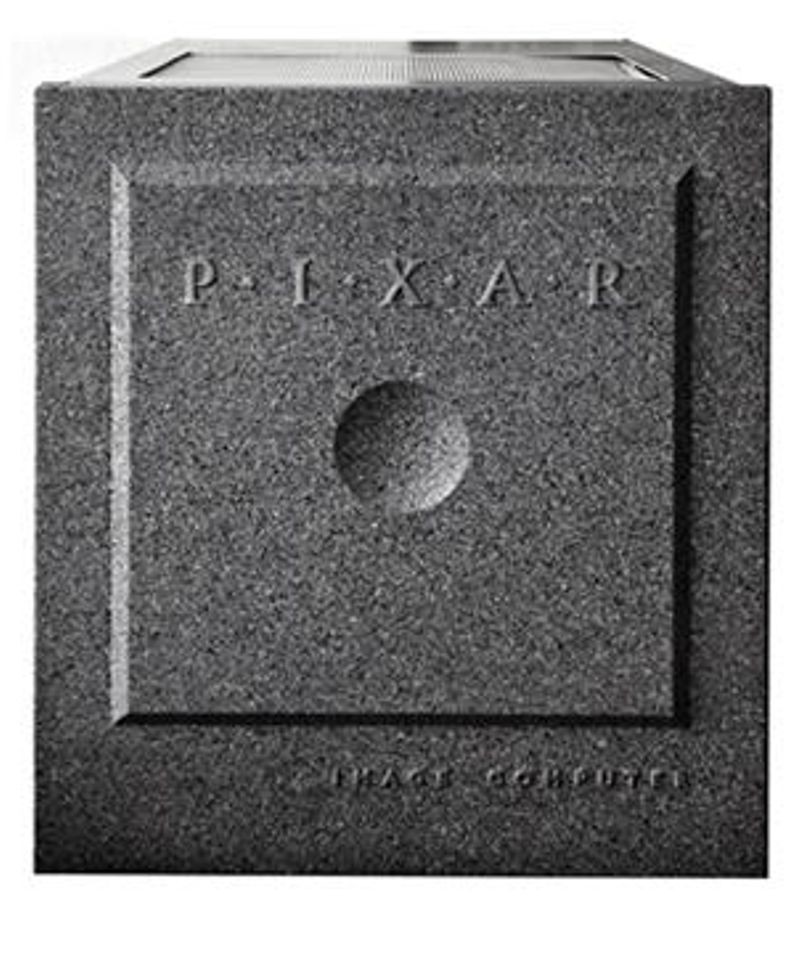

Pixar Image Computer, 1986. This computer was used for generating images from complex data sets such as CAT scans, oil exploration or scenes from a virtual world. Disney purchased several dozen for use in animation. CHM# 102621974 Photo: ©Mark Richards

Jobs spent the next ten years away from Apple but was by no means taking time off. In 1986, he bought the computer graphics division of Lucasfilm, renaming it Pixar. Pixar had started as a manufacturer of high-performance graphics hardware. Its main product was the Pixar Image Computer, a rendering engine for animation. While the computer was technically sophisticated, its high cost (about $130,000) made it appealing only to well-funded customers such as advanced medical research institutions and government laboratories. There was one exception: Disney. The legendary studio bought several dozen of the systems for use in animation.

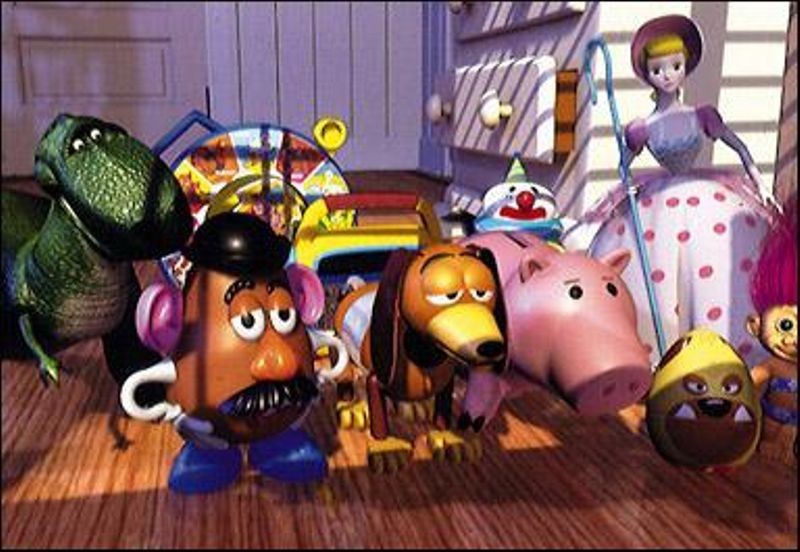

Scene from Pixar’s computer-generated feature-length film Toy Story ©Pixar

Disney’s interest in Pixar’s hardware, however, was not enough to save the company from lackluster sales. Pixar finally sold its hardware division in 1990. Jobs shifted Pixar’s focus and concentrated it on producing short film sequences and commercials. The next year, partly due to the success of Pixar’s Oscar-winning “Tin Toy” short film, Pixar and Disney agreed to produce a computer generated film called “A Tin Toy Christmas.” Hollywood had met computing, and together Pixar and Disney would move computer-generated graphics from the niche of special effects to the heart of filmmaking itself.

Pixar brain trust: Ed Catmull, Steve Jobs, John Lasseter ©Pixar

Using groundbreaking computer technology and some of the most skilled animators and storytellers in the world, Pixar produced the blockbuster film Toy Story, released in 1995. Toy Story proved that a feature-length motion picture could be entirely animated by computer and also made wildly entertaining. Pixar exploded as a Hollywood powerhouse, and its partnership with Disney produced some of the biggest box office hits of the decade. Jobs sold Pixar to Disney in 2006, earning more than $7 billion from his initial $10 million investment and becoming Disney’s largest single shareholder.

The NeXT Cube (1990) was a masterpiece of engineering… but was too expensive. NeXT evolved into a software company after the Cube and several other NeXt hardware products failed in the marketplace. NeXT’s greatest innovation was the NeXTSTEP operating environment CHM# 102626734

While Pixar was beginning to work its magic, Jobs was working in parallel on another computer startup. His new company, NeXT, set out to build high-performance UNIX workstations for the educational and scientific market. The machines, introduced in 1990, were prototypically Jobs: elegant, well-engineered and easy to use, but the NeXT “Cube” was too expensive for mass appeal. Although it had high-performance hardware, the NeXT delivered its greatest innovation in the form of its “object-oriented” operating system, NeXTStep. Yet despite its originality and power, the NeXT system struggled to find its place in the market. It did, however, have a significant claim to fame: a British scientist named Tim Berners-Lee would write the program for the World Wide Web on a NeXT. In 1996, Apple bought NeXT, mainly for its software and operating system, and Jobs returned to Apple as a consultant.

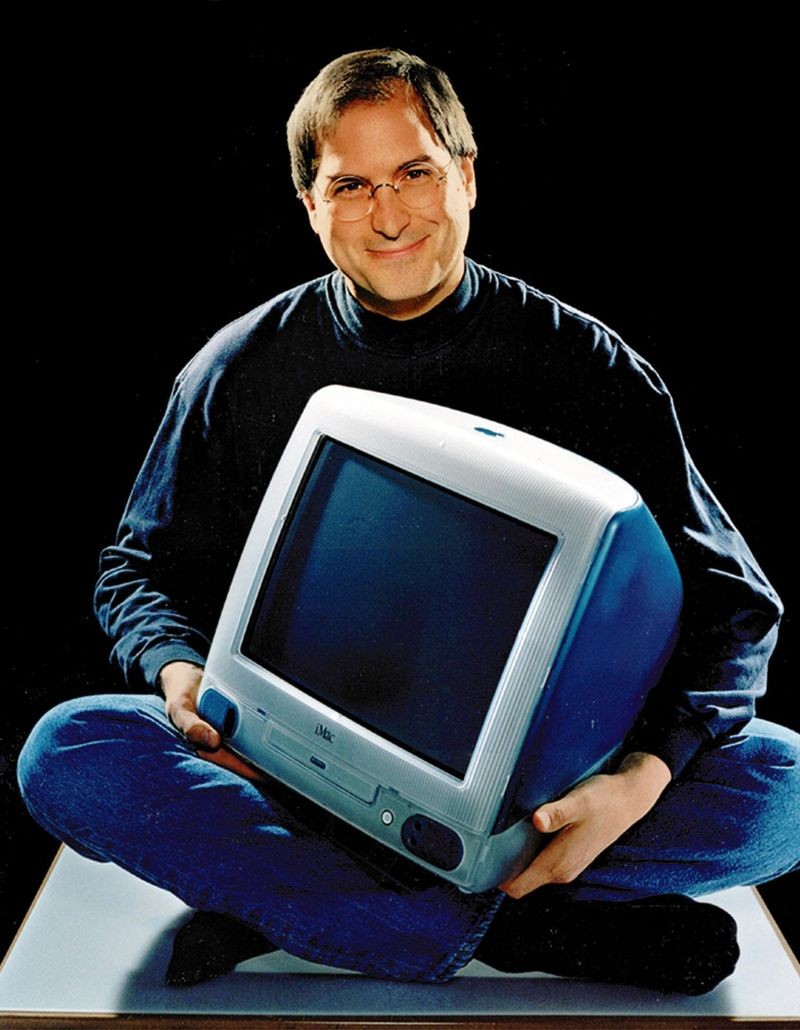

Jobs with the original iMac, 1998 ©Apple Inc. / Moshe Brakha

Jobs joined an Apple that was in no better shape than the company from which he had been unceremoniously fired. It was losing money at a catastrophic rate. Its product line was bloated and confusing. Its marketing was ineffective. Its innovations in user interfaces and software had long since been eclipsed by Microsoft’s Windows and applications for the Windows system, which had become the de facto standard for personal computing worldwide. And Apple seemingly had no strategy for capitalizing on the internet, which was exploding as a force in home and business computing.

A year after returning to Apple, Jobs was named interim CEO, replacing Gil Amelio in July 1997. Apple had lost more than $700 million the preceding quarter. It was running out of money and it looked as if it might not survive. Jobs quickly sought new financing, terminated languishing projects, fired hundreds of people and focused the company on just a desktop computer and a laptop for professionals and for consumers. The first desktop computer from the new Jobs era was the iMac (1998). Ultimately available in several colors of the rainbow, the iMac emphasized connection to the Internet and—Jobs’s mantra—simplicity. Out of the box, the iMac could be on the Internet in just two easy steps. “There is no Step 3,” Apple claimed. The iMac and its distinctive design also marked the first tangible collaboration between Jobs and Jonathan Ive, the British-born designer with whom he would form a legendary partnership.

In 2000, the Apple board removed the term “interim” from Jobs’s CEO title, cementing his permanent return to the company he had co-founded. It must have seemed a glorious triumph for Jobs personally. For the Apple faithful, it represented a glimmer of hope that the resurgent company they loved might have a chance. Perhaps no one within or outside Apple—with the possible exception of Jobs himself—could foresee that the company was embarking on one of the most remarkable decades any company in any industry had ever experienced.

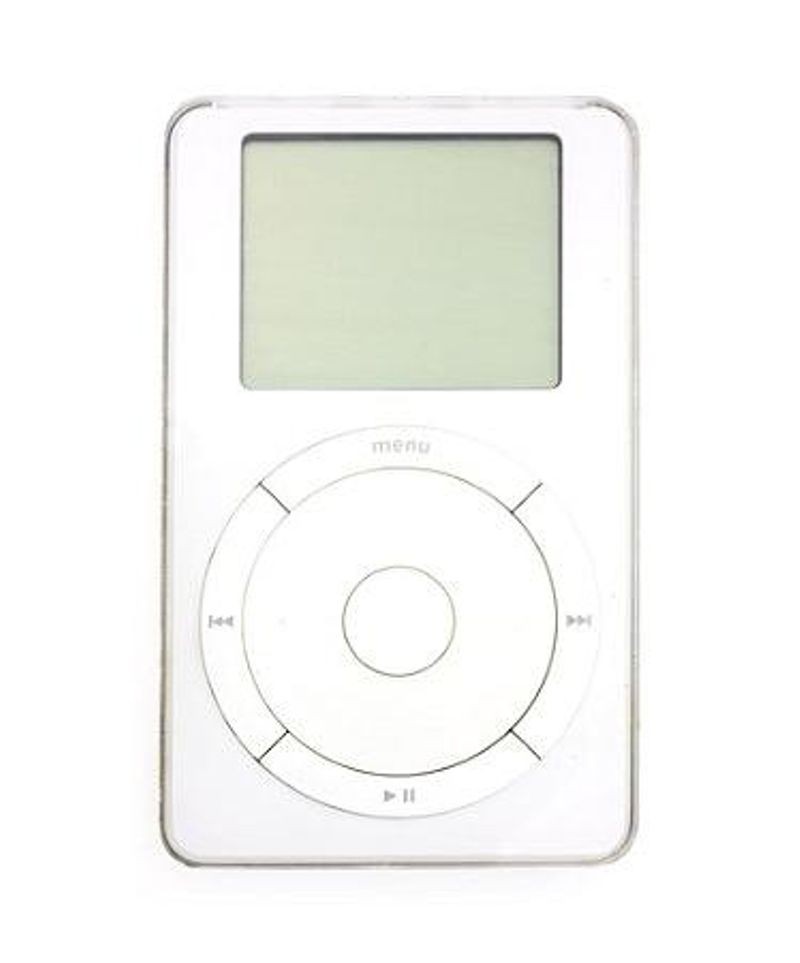

iPod Evaluation and Test Prototype (2001). The original iPod had a miniaturized 5GB hard disk drive and could “store 1,000 songs in your pocket.” CHM# 102633636 Photo: ©Mark Richards

Innovations came in rapid-fire succession. In 2001, Apple introduced OS X, the new operating system for the Mac platform. OS X marked the total redesign of the Mac operating system from the ground up. It was a direct result of Apple’s NeXT acquisition and was based on NeXT’s OPENSTEP environment and the BSD Unix system developed at UC Berkeley.

That same year Apple opened its first retail store, in Tysons Corner, Virginia. It was a daring step at a time when computer companies had long since abandoned their own branded retail outlets in favor of “big box” electronic superstores and internet shopping. Like Apple products themselves, the stores reflected an austere simplicity and were organized not by product category but by how Jobs believed people wanted to use them. Products were stylishly arranged for direct use by customers in a minimalist, almost laboratory-like zone of utilitarian consumerism. As usual, Jobs sweated the details, ensuring the marble floors were the right color and the washroom signs were not too obtrusive. A “Genius Bar” staffed by Apple experts answered customer problems on-site. The stores were hailed as a perfect blend of the products Apple made and the brand itself.

The most momentous event of 2001, however, was the introduction of the iPod digital music player. Although not a new idea, Apple’s take on the device featured an easy-to-use interface and, thanks to new miniaturized hard drive technology, a prodigious amount of music storage. Jobs announced the iPod with the slogan “1,000 songs in your pocket.” Music was sync’d to the iPod through the iTunes software application, another Apple innovation. As of October 2011, more than 300 million iPods had been sold worldwide.

In 2003, Jobs introduced an even more radical innovation: the iTunes store and music management system. The iTunes platform represented the successful integration of retail music, portable player, e-commerce, digital rights management and a simple desktop environment where users could manage their music libraries. Jobs convinced powerful and deeply skeptical music company executives that, together, the iPod and iTunes system represented a legitimate and profitable alternative to music piracy, which was then rampant through bootleg services such as Napster and LimeWire. In exchange, Jobs won a revolutionary concession from the music industry: flat-rate pricing of 99 cents per downloaded song. The iTunes concept revolutionized the retail music industry, and sounded the death knell for brick-and-mortar record stores. As of October 2011, the iTunes music store had sold more than 16 billion songs.

The iPod marked a turning point in Apple’s strategy. Jobs sought to move Apple beyond computers and into Apple-powered consumer devices. It was a very bold gamble, and the success of the iPod and iTunes showed that the strategy could win on two levels: it eroded traditional industry structures, and it catapulted Apple into a widely recognized global consumer brand.

iPhone, 2007 CHM# 102716304 Photo: ©Mark Richards

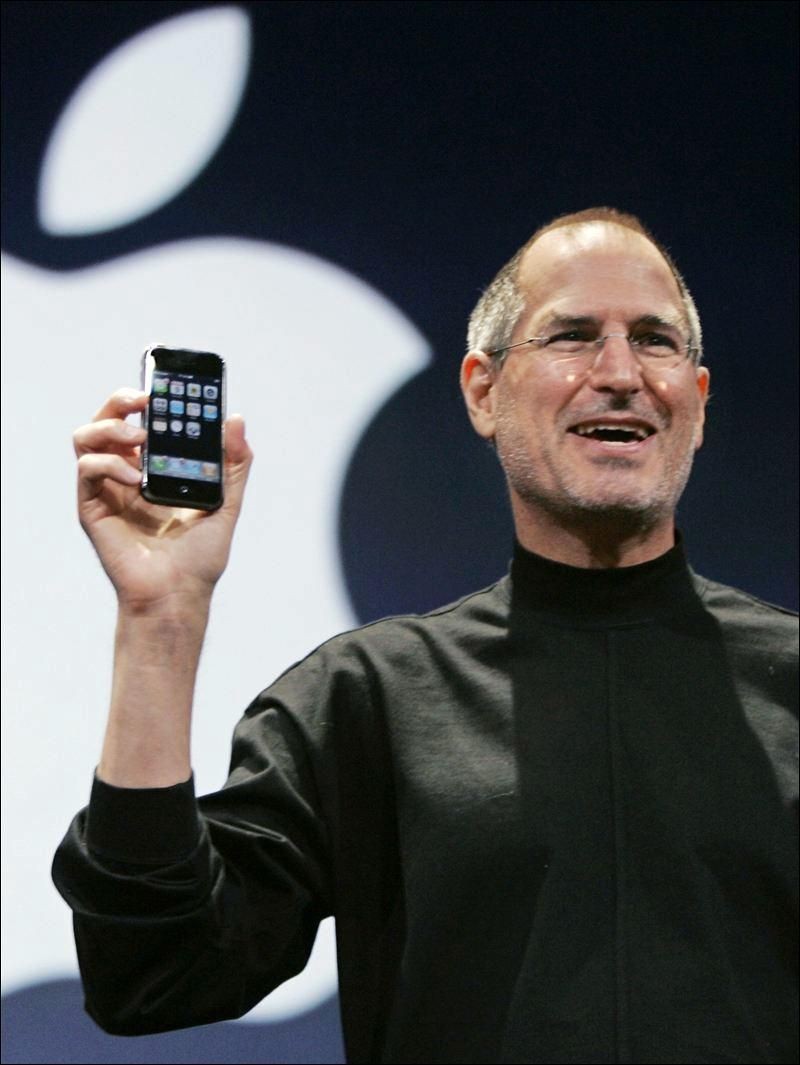

Steve Jobs unveiling iPhone to the world

At the 2007 Macworld trade show, Jobs announced that Apple would drop the word “Computer” from its name and become simply “Apple Inc.” The move solidified the profound shift in the company’s direction and signaled its seemingly unlimited ambition in the multi-billion dollar market for switched-on consumer products. At the Macworld show, Jobs also saved his customary “one more thing” portion of his presentation for another blockbuster announcement: the iPhone. He described it as nothing less than the re-invention of the telephone: a combination “widescreen iPod with touch controls,” a “revolutionary mobile phone,” and a “breakthrough Internet communicator.”

When the iPhone went on-sale, thousands of people worldwide waited patiently outside Apple stores, sometimes for days, to be first to purchase one. This remarkable show of brand loyalty reflected how deeply Apple products had connected with their users on a personal level. Like the iPod before it, the iPhone sold briskly and transformed another industry (telephones) by making the smartphone an established category of “must-have” device, for everyone from teenagers to business executives. The iPhone was a computer at its core: it ran Apple’s iOS operating system, which was based on Mac OS X, its desktop operating system. To add extra capabilities, the user downloaded ‘apps’ (applications) from the iTunes App Store, launched in July 2008. By October 2011, more than 18 billion apps had been downloaded.

Jobs’s last major product launch was the iPad, a tablet computer optimized for media consumption, quick emails, and web browsing. Like the previous iPod and iPhone iOS devices, the iPad pioneered an entirely new set of experiences and possibilities for users. Apple introduced the iPad in 2010, and within a year software developers had introduced more than 100,000 apps for the device, ranging from navigation aids to cameras to wildly popular games and ways both to create and consume every type of media. Yet unlike the iPod and the iPhone, the iPad did not simply improve upon a major segment of consumer electronics: it invented a largely new category. The iPad was another triumph of Apple engineering and marketing, one deeply shaped by Jobs at every step.

Outpouring of remembrances and ‘thanks’ to Steve Jobs, Apple store, Palo Alto, California, Oct 8, 2011 © All rights reserved by troialynn

Certain qualities persisted throughout Jobs’s career, from the Apple-1 to the iPad. One was an unshakable determination to create something of beauty, in the aesthetic and engineering senses of that word. Another was enormously successful risk-taking, from selling his van to finance the Apple-1 to perfecting the music player, telephone and tablet computer. Another was Jobs’s uncanny ability to focus on a larger vision—and, in the case of consumers, to anticipate whole categories of needs that few of his rivals saw. Finally, especially in the iOS devices, Jobs engaged in “ecosystem thinking,” a drive to integrate radical new hardware advances with bold new software and services. iTunes and the App Stores were as critical to the success of iOS devices as the hardware itself, and established Apple not simply as an unparalleled product company but also as a global content distribution company.

Jobs once said his goal in life was “to make a dent in the universe.” Isaacson asserts that Jobs changed seven industries: personal computers, animated movies, music, telephones, tablet computing, digital publishing and retail stores. At the end of this life, Jobs saw Apple surpass Exxon as the most valuable company in the world as measured in market capitalization. Ultimately, Jobs made his dent, and more. A fitting tribute, borrowed from the tomb of English architect Sir Christopher Wren, might be: Si monumentum requires circumspice. “If you seek his monument, look around you.”

Steven Paul Jobs was born February 24, 1955, and died October 5, 2011.