This year, the Computer History Museum honors Harry Huskey as a CHM Fellow. Fellows are unique individuals who have made a major difference to computing and to the world around them. Huskey was born in 1916 in Bryson, North Carolina, when the Battle of the Somme was raging and Pancho Villa was on the lam. He is from that first generation of computing pioneers who worked at the dawn of the computer age in the mid-1940s. In this first generation, people were asking what an electronic calculating machine might do and building real working systems themselves to explore that question.

There were no computer engineers or computer scientists—that was decades in the future. “Computer people” in the first generation were often physicists or mathematicians as well as engineers. All were new to this exciting new field of electronic digital computing. Huskey, a mathematician, was a key participant in this early period, working with several of the most important machines and people in the history of computing.

Huskey received his bachelor’s degree in mathematics and physics at the University of Idaho (1937) and a masters and doctorate (1943) in mathematics from Ohio State University. For his doctorate, Huskey worked under professor Tibor Rado, who, in WW I, had escaped a Siberian military prison, hijacked a train from Siberia to Vladivostok, and somehow made it back to his native Hungary.

Huskey’s first job was teaching mathematics as an assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania, mainly to U.S. Navy students during WW II. While there, he applied for classified work at Penn’s Moore School of Engineering. Without knowing the specific details of the work, Huskey soon learned that he would be a team member on the legendary ENIAC project—the first large-scale electronic computer (1946). Huskey recalls:

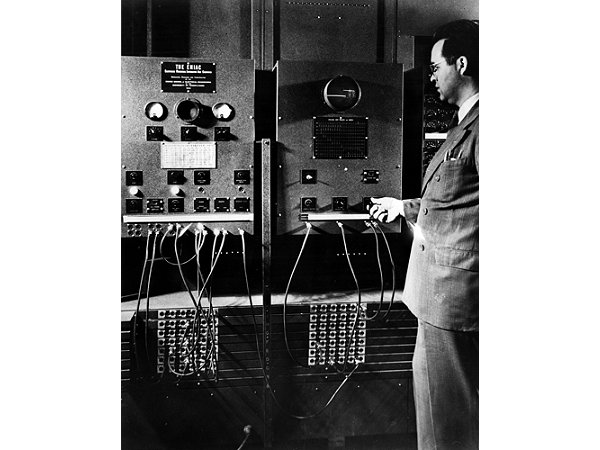

Huskey in front of the ENIAC main control panel.

On the project, Huskey’s task was to interface the punched card reader and punch to ENIAC and to write the impressive technical manuals that described ENIAC’s operation.

Once ENIAC was officially announced to the world as a working system on Feb 15, 1946, Huskey left the project and took up a summer teaching position at Ohio State University. While there, he received a telegram from Douglas Hartree, a famous British mathematician and physicist, whom he had met during the ENIAC project:

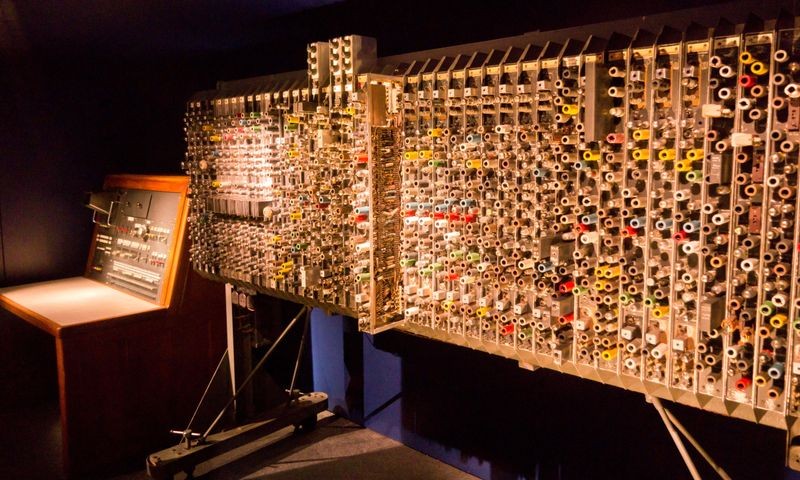

The original Pilot ACE, on display at the Science Museum, London.

When he arrived at NPL—the National Physical Laboratory—Huskey, after adjusting to “smoked fish for breakfast,” began working on a prototype computer whose direction was ultimately under Alan Turing. This was the Pilot ACE (Automatic Computing Engine), one of the earliest electronic computers built in the U.K. The Pilot ACE was a smaller version of the full ACE, designed by Turing and built some years later. Both machines were intended to embody Turing’s grand idea that computers could be universal, that is, that they could perform any logical operation through software rather than purpose-built hardware. The big idea behind all this was the notion of a stored-program. A stored-program machine keeps its operating instructions and data in memory, where they can change dynamically. Rather than building a separate machine for each purpose, Turing’s machine, using the idea of a stored-program, could become any machine. Being able to store its own program is one of the defining characteristics of what we think of as a computer today.

Huskey spent several months working, as did most of the 3-man team, on algorithms and instruction sets.

This machine became the Pilot ACE and ran its first program on May 10, 1950, by which time Huskey had left NPL to return to the United States. It quickly became popular with mathematicians and was kept very busy until its retirement in May 1955. A commercial version, called the Deuce, was built and sold by English Electric, probably the first commercially produced computer in Britain.

Huskey remembers Turing:

Alan Turing, winning second place, at the NPL Sports Day, December 1946.

In December of 1948, the peripatetic Huskey had left NPL to design and lead fabrication of the Standards Western Automatic Computer (SWAC), a US government-sponsored computer that would support mathematicians at UCLA and the air force at a new center for numerical analysis. The machine was meant to be an interim computer while manufacturers caught up to the independent efforts of universities and government. It ran, with some modifications, until 1967. Huskey, who says later that he learned his electronic design skills from a textbook as he went along on the Pilot ACE project, remarkably led the SWAC design as well. There were some thorny problems to solve. For example, here Huskey describes the primitive state of manufacturing the cathode ray tube memories that SWAC used:

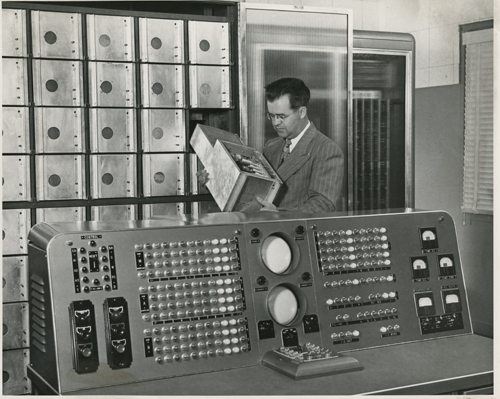

Harry Huskey examining one of SWAC’s Williams Tube memory units, tubes often rendered useless by lint.

At that time of its completion in July 0f 1950, SWAC was, for a brief period, the fastest computer in the world. It is also one of the earliest computers in the United States and lived on, in modified form, at UCLA until 1967.

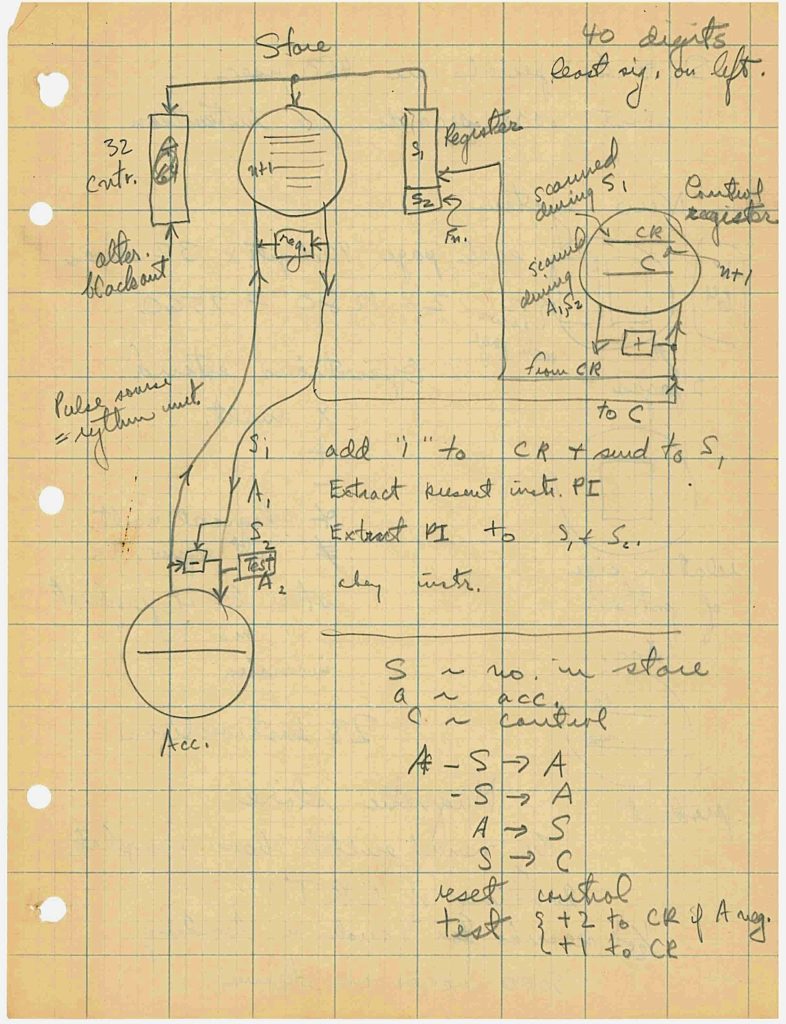

Drawing describing SWAC logical flow, Harry Huskey papers, Computer History Museum.

During his SWAC work, Huskey also appeared on You Bet Your Life, a live television show hosted by Groucho Marx, in which the mild-mannered Huskey tries to explain what SWAC does. Groucho, as usual, takes no prisoners and ties everything (and everyone) into knots. You can listen to the episode, which first aired May 10, 1950, here. The Huskey sequence starts at 15:08.

After five years on the SWAC project, Huskey accepted a teaching offer at UC Berkeley, beginning in 1954. While there, he designed, under contract, a remarkable computer that embodied the then-heretical notion that one person could use a computer all to themselves, without the need for operators to intercede.

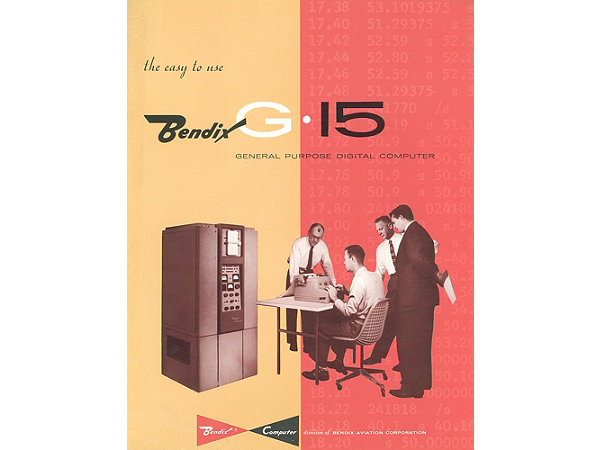

While at Berkeley, he designed the G15, which was manufactured and sold by Bendix Aviation Corporation. The G15 was the first computer that could perhaps be called a “personal,” computer, in that one person alone could operate it. Introduced in 1956, it was targeted at scientific, industrial and engineering users who could simply sit at the machine themselves and solve problems right away. It’s difficult to appreciate how big a difference this approach had on the ‘thinking style’ of G15 users in which multiple variables can be changed quickly and easily on a computer, allowing for iterative problem-solving of a type that is not possible with existing computers (which were, by and large, enormous room-filling complex systems professionally managed and mediated).

Bendix G-15 promotional brochure.

The G15 didn’t fill a room—it was the size of a refrigerator. It costs just under $50,000 or could be rented for about $1,500 a month. These are big amounts for the 1950s but a fraction of the other systems, which could cost millions of dollars. CHM has a G-15 in its permanent collection.

In 1967, Huskey left Berkeley for the newly-opened University of California at Santa Cruz campus, which he joined as faculty and founder and director of its computer center, a position he held for 10 years. He taught and advised other universities on setting up their own computing centers and computer science programs, including a 2-year stay in India at IIT-Kanpur advising on their new computing activities there on a Ford Foundation and USAID program. He also advised the University of Yangon (Rangoon), Burma with UNESCO support. He retired in 1986 and lives in Santa Cruz, California.

Harry Huskey will be joining the CHM Fellow Awards this year to accept his award in person.